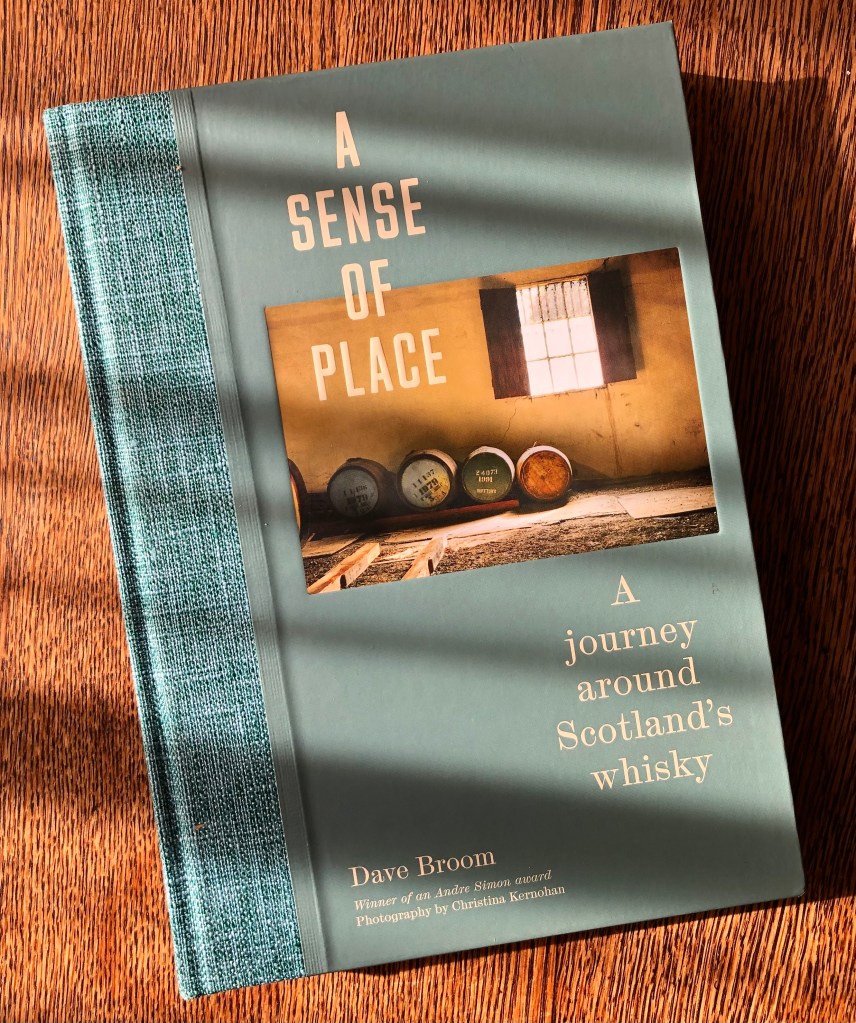

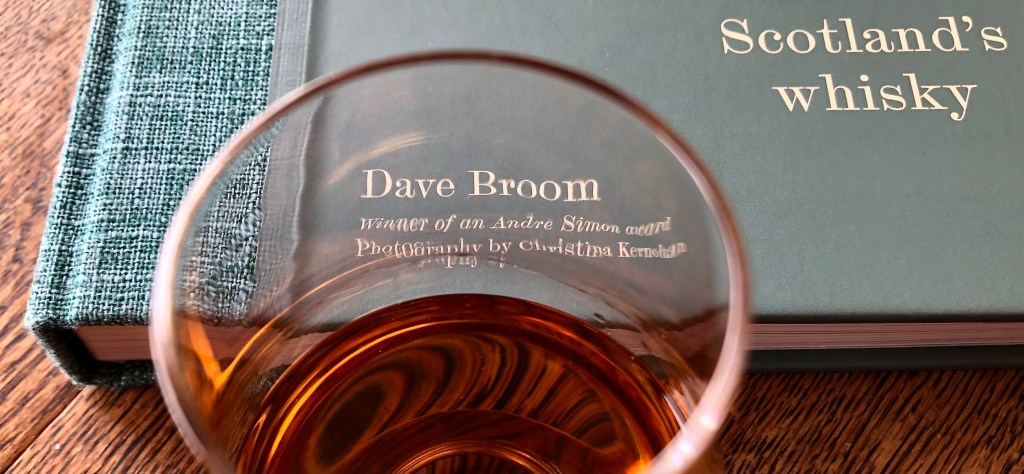

A SENSE OF PLACE

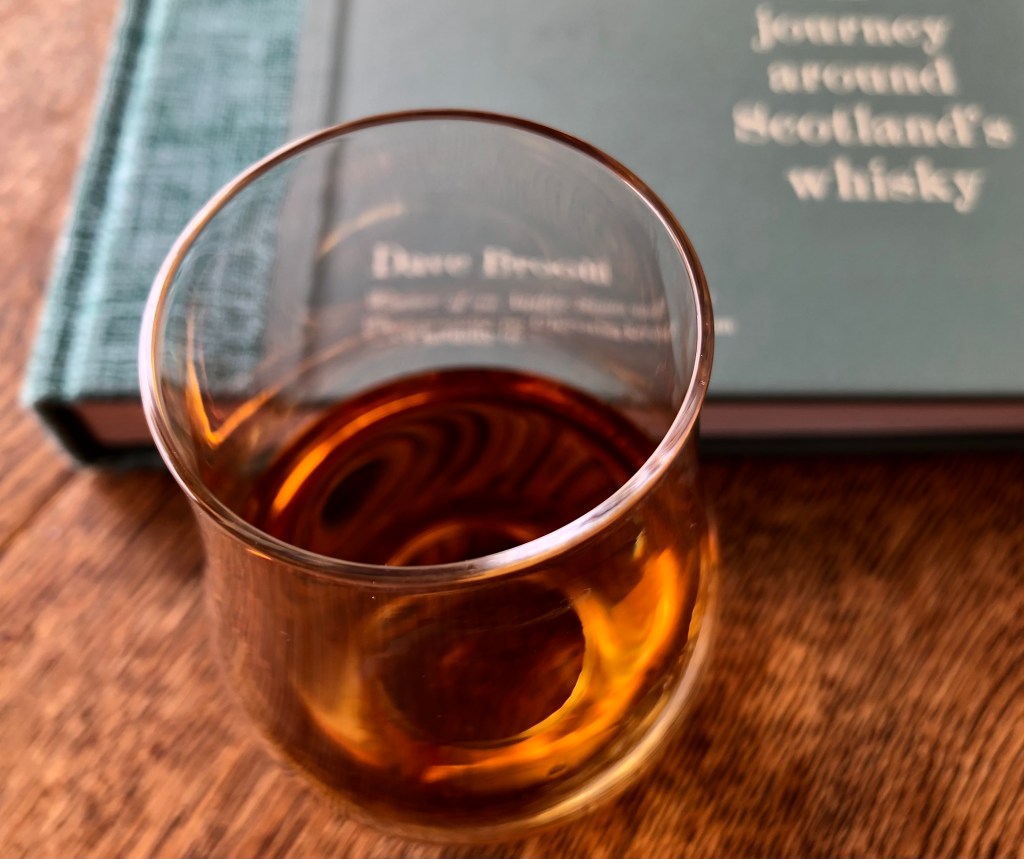

a journey around Scotland’s whiskyBY – Dave Broom. Photography Christina Kernohan.

PUBLISHER – Mitchell Beazley, London.

YEAR – 2022

I first learned of Dave Broom’s absolutely beautiful new book, A Sense of Place, from Issue 3 of The Angels’ Share, itself an absolutely beautiful journal on all things scotch whisky. Any scotch fan owes it to themself to subscribe to this journal. Its first year’s three issues have all come out, each a considered, stylish, informative, utterly pleasant read. In-depth articles and interviews are accompanied by clear, gorgeous photos, arranged in thoughtful and creative layouts.

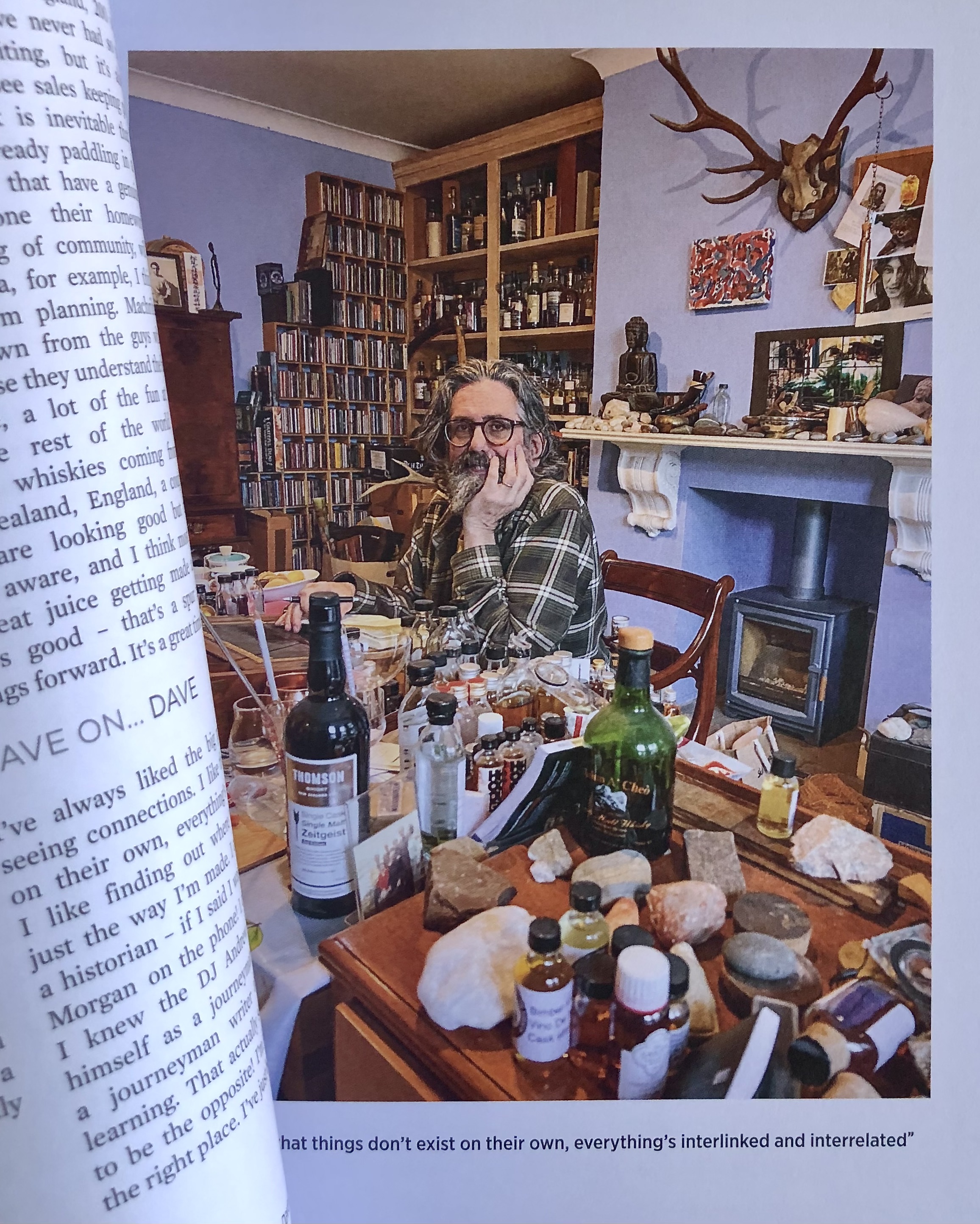

Broom and his book make a natural subject for The Angels’ Share, not only in substance but in sensibility. A Sense of Place could be one of the journal’s articles that just kept going until lo and behold it had grown into a book.

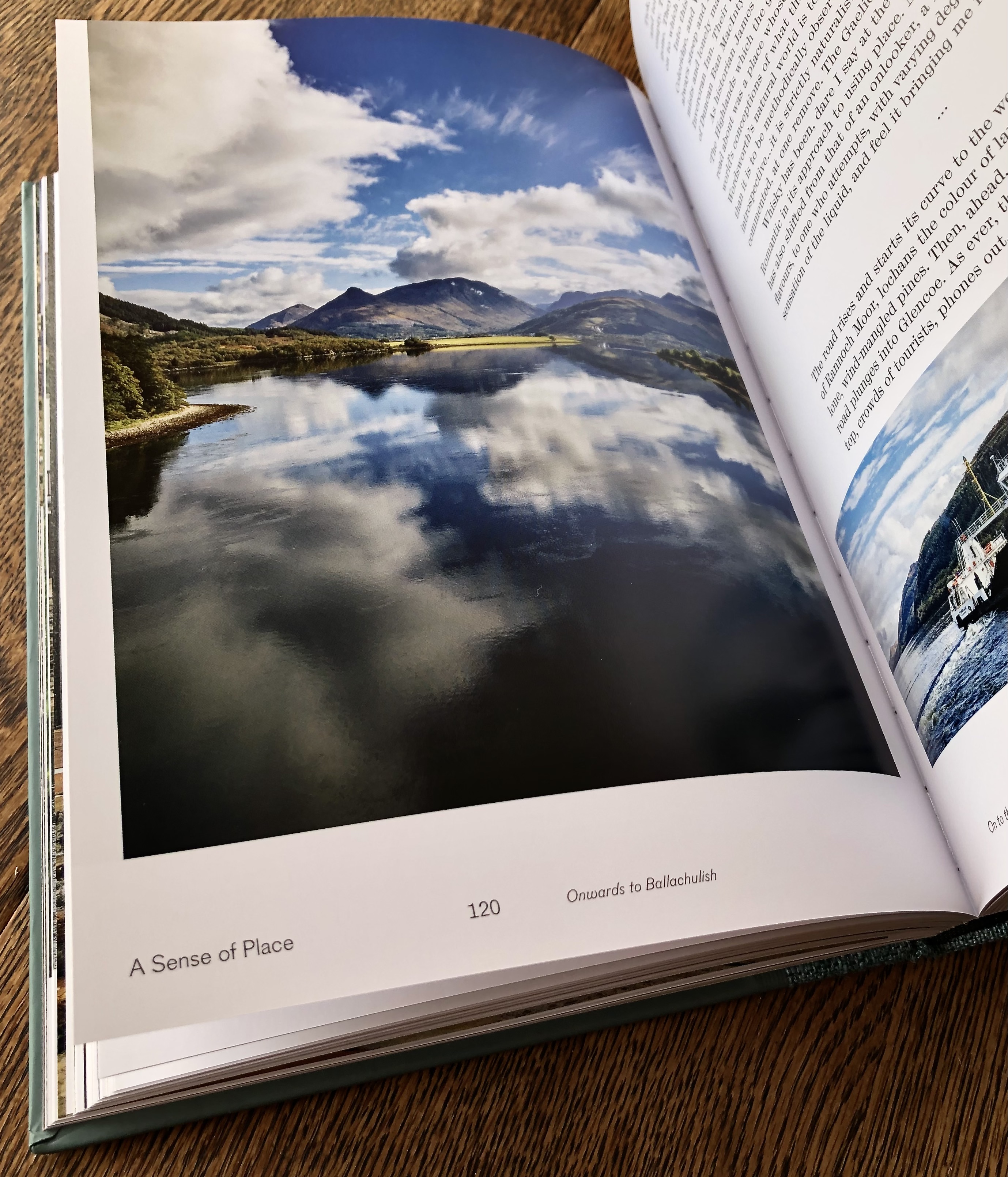

Broom’s writing flows from prose into poetry into conversation, with the ease and agility of a fresh water stream maneuvering through the stones it patiently shapes. These fluid shifts in language pass naturally, creating an effortless rhythm that catches eye, ear, and thought.

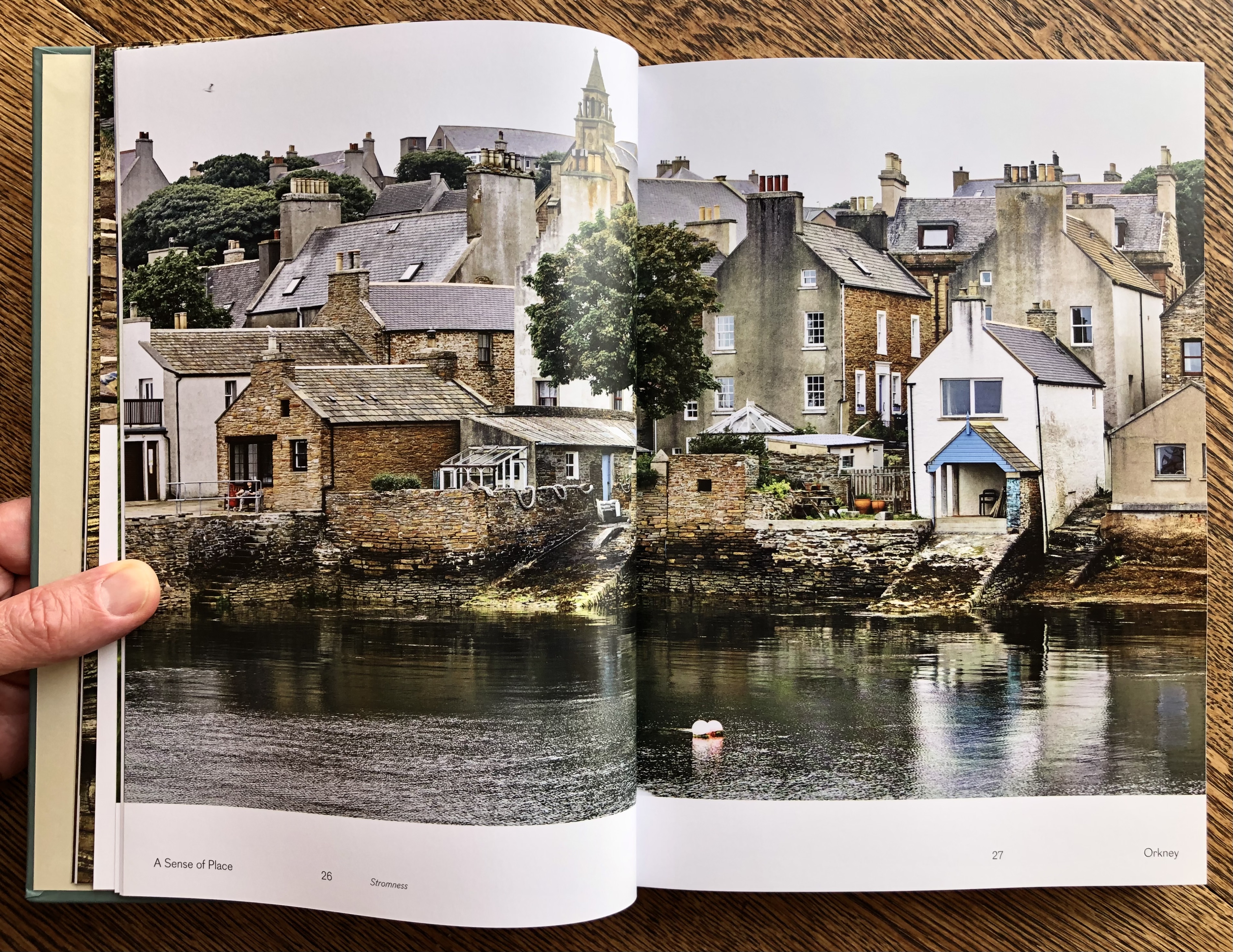

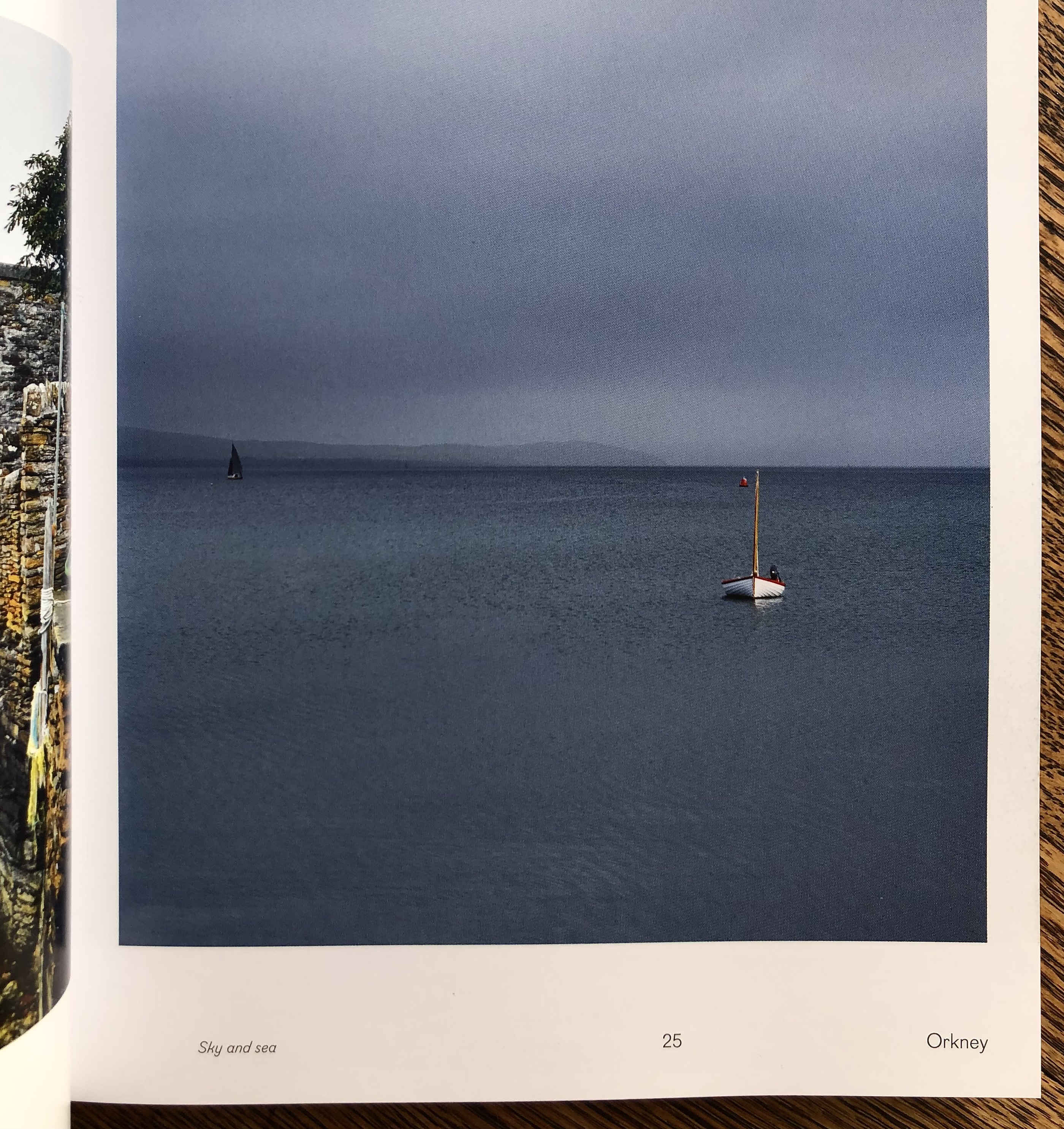

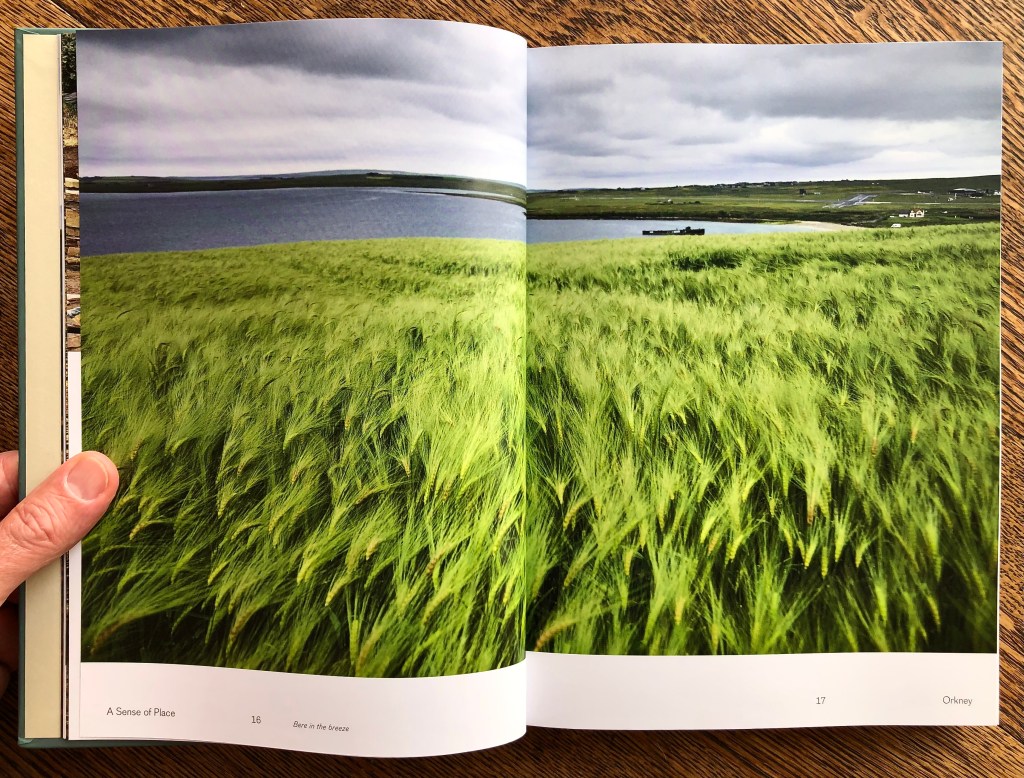

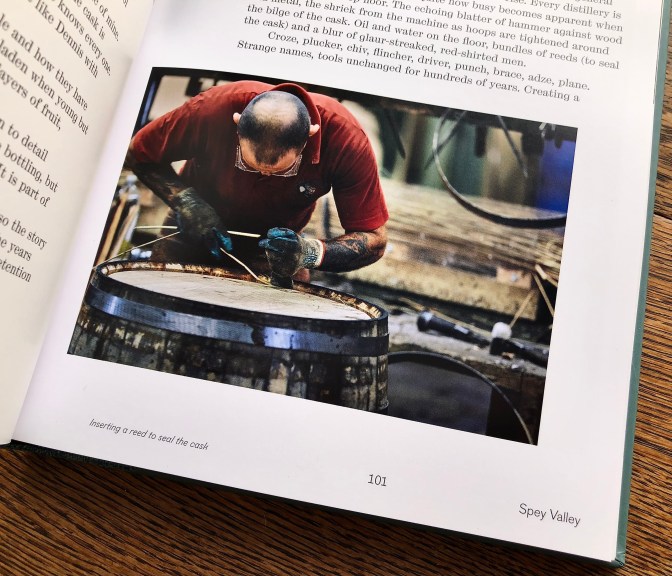

A generous array of photographs by Christina Kernohan adds to the book’s structure and appeal. The photographs are integral to the writing. Their organic integration into the text is no doubt largely due to the fact that they were not taken after the writing was done, to fill in gaps or illustrate with redundancy what had already been expressed adequately in words. Rather, Kernohan accompanied Broom as he journeyed across Scotland conducting his research and interviews. From one page to the next, Broom and Kernohan seem to feed off one another, effectively co-authoring the book in their respective modes of writing—words and photos.

One result is to belie the old adage that a picture is worth a thousand words. Here their value is equal. The words and the images share a real-time aliveness, a combination of spontaneity and light-touch precision that creates a sense of inevitability. Like the country and its whisky that the book explores, the book itself seems to have been forged in the long-haul push and pull between human and nature. It’s there. At once whole and in process.

The journey begins in the north, in Orkney…

…best known among scotch fans for the distilleries Highland Park and Scapa. Broom mentions these stalwarts. But his attention is focused on setting up the journey we’re about to take. The book’s major thematic braid is established—place, community, and sustainability.

The Orkney region is a cluster of islands just off the northern coast of the Scottish mainland. Broom notes the region’s continued cultural identification with its early Neolithic roots, long before it became a part of Scotland in 1468. This merger came about when King Christian I of Denmark, Norway, and Sweden, brokered the islands to Scotland as part of a political marriage between Christian’s daughter, Margaret, and King James III. A land deal in lieu of a more traditional dowery. Not quite as romantic as the rolling green hills and slate blue waters of Orkney itself.

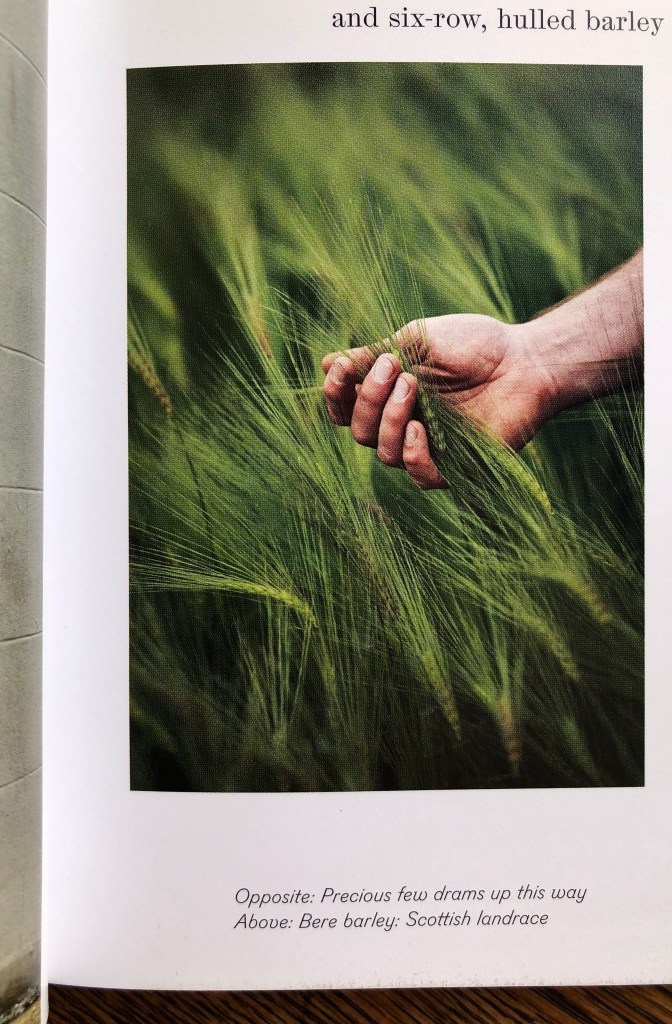

Threading through this ever unfolding history, Broom notes, is bere, a variety of six-row barley indigenous to Orkney.

A good portion of this chapter is devoted to the grain. Broom uses it to introduce the idea of conditions as a key factor in evolution—a creative factor, he suggests, operating with intention, rather than within evolution as a process of fate’s fickle twists. Referencing poet and essayist Gary Snyder in his book, The Practice of the Wild: Essays, Broom quotes:

‘We could say that a food brings a form into existence: huckleberries call for bear, the clouds of plankton call for salmon, and salmon call for orca and seal… Us? The whole of the earth calls us into existence. The condition dictates the response.‘

And so, in Broom’s own words:

Scotland’s geology and climatic conditions called barley into existence, and barley made people settle down and start farming. The barley gave bread, then beer and, finally, it called whisky into existence.

Jump ahead to the end of the nineteenth century, and whisky is no longer just an agricultural product made by farmers but a burgeoned industry. The industry drops bere for other imported barleys that are easier to harvest and produce higher yields. Jump further ahead to the twenty-first century, and the historical importance of bere to the place known as Orkney is recognized. Bere’s nutty, earthy flavor conjures deep cultural memory. This tough, ancient grain, marginalized for a time by economic concerns, is now cultivated as both a business endeavor and a matter of cultural sustainability.

The story of bere’s survival and influence under the care and carelessness of generations of Orkney farmers and distillers allows Broom a literal field in which to discuss issues relating a community’s relationship to the place they live, its weather and resources, and how these in turn shape the developing culture. Foods become symbols of a people. Landscapes inspire their poetry and music. Weather fuels their temperament.

Over time, kings and subjects have come and gone. But bere has been a constant throughout Orkney’s long history, feeding people, providing them with work and income, a beautiful view, its constancy offering assurance, confidence, a tangible connection to cultural roots embodied in literal roots.

Subsequent chapters elaborate on the motifs established in the first.

In the chapter devoted to the highly influential Speyside region, Broom explores the ecosystem of large verses small distilleries in relation to specificity of place. Observing the modernized facilities of the sizable, long-standing, world famous Glenfiddich Distillery, Broom asks:

Is there a point when you get so big, that the intimacy of [place] is impossible to comprehend? No matter how impressive the new still-house is, you feel something slipping away, because scale creates distance. Provenance, heritage and place are vital elements for single malt, yet large distilleries with their computers can seem oddly detached, rootless places.

These questions continue in variation:

For example, what distinguishes “terroir” from “place”? In short, terroir is generally used in reference to the impact of geological and climatic conditions on flavor, while place additionally considers the people who have derived their culture in response to nature’s conditions.

Similarly, Broom explores sustainability in its common association with nature preservation, but also the preservation of community. Here those concepts of terroir and place engage in a balancing act between the needs and evolution of nature itself, and those of the people who depend on it, identify with it, exploit it, seek to subvert it, and occasionally have the insight to care for it.

Leaning further into the notion of human action as both distinct and responsive to nature, the concept of a whisky “region”—with a name, boundaries, categorized characteristics, arising from a combination of political and economic concerns—is neatly unpacked and questioned:

‘Speyside’ is a modern construct. Prior to the term’s arrival, whiskies from the area would have been known as Strathspey, maybe North Country. Before that, the shorthand for the area was Glenlivet, a catch-all term that had nothing to do with geography… The Scotch Whisky Regulations 2009 define Speyside [according to] the Moray Electoral Arrangements Order 2006(b)… Odd that something that purports to be a geographical region is defined by political boundaries rather than natural features such as, say, the Spey watershed, although since that would remove the whisky towns of Elgin, Forres and Keith from the definition, problems would undoubtedly ensue.

The other issue lies in the assumption that the drawing of a whisky region’s boundaries also fixes its flavour. There is no single Speyside style. It’s as elusive as one of the river’s salmon... [But] if distillery character supplants region, can we even speak about place? I’d argue it is the only way. Place is what lies beneath the branding.

Inevitably Broom hones in on the people involved in all of this. Not a general notion of a local population, but specific families and individuals:

I think of the McBains, the Grants and Gordons, and all of the other families across the area, their stories interweaving through the history of this area. Not brands, not marketing or PR, but people’s tales… The story of the Grants of Glenfiddich and Balvenie is also the story of Speyside—the move to towns, the adaptation to new ways, the years at the service of blends, the rise of single malt, the tourists, the retension of crafts—all here in one place.

Mapping the lives of a people inscribes nuance and meaning into the map of the place where they live.

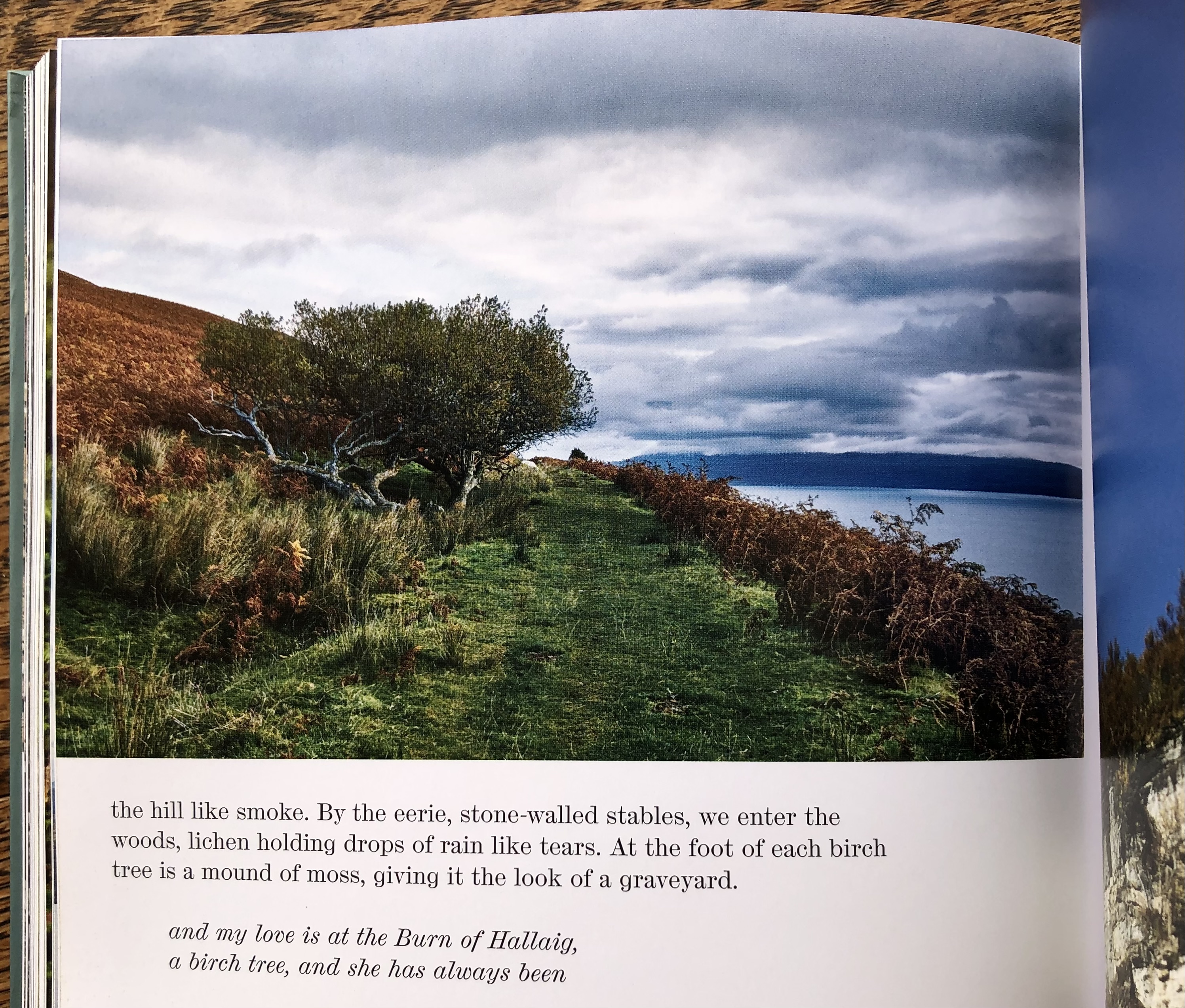

In the chapter on Hebrides, a west coast region comprised of well over a hundred islands, Broom explores the smaller new distilleries like Raasay and Torabhaig, both established in 2017. Founded in an era far more aware of climate change and limited natural resources than past eras, the foundational practices and the identities, in other words the cultures, of today’s young distilleries emphasize indigenous heirloom grains, low carbon emissions, reusables, mutually beneficial partnerships with small local farmers, and an imperative to experiment. Broom again:

Although single malt only emerged as a significant category in the 1990s, it is now sufficiently well established to mean that any new distillery has to find ways to cut through not only all of the established Scotch single malt brands, but the growing number of whiskies from around the world, hence the experiments with barley varieties, yeasts, distillation techniques and casks that you see here, or in most of the other new distilleries… Part of discovering what the distillery is also involves understanding the peculiarities of its location.

New distilleries have another imperative as well. Many of the Hebrides islands have aging populations. The young people leave for lack of viable employment. So in addition to tending to the land, new distilleries renew communities by providing not only jobs but sustainable careers. A young person can buy a house and stay. This in turn creates the conditions of opportunity that whisky tourism brings—a need for cafes, shops, hotels. And residents will need their schools, doctors, transportation, infrastructure. A sustainable local economy dependent on a sustainable handling of natural resources. A culture that thrives so long as nature does too. Broom:

A whisky bioregion isn’t defined by a nineteenth-century tax line or political boundary, but by the distiller asking, ‘why here?’, a process which makes you look deeper and more intently at what is around you… The individual distillery is the terroir. The bioregion is the context. Work, folk, place.

Islay is among the most famous whisky regions of Scotland, its distilleries well regarded for their overwhelming emphasis on peat-smoked barley. Distilleries in Hebrides, Speyside, Orkney, or any other region might also put peat to use in their malting process. And some Islay distilleries will even forgo it. But Islay is without doubt defined by its intense maritime peat.

Broom, however, might argue it is actually defined more by its people, who have defined themselves in relation to the place where they find themselves, and maintain a circular relationship to it:

The first time the phrase ‘whisky is about people’ was said to me was in my first meeting with Jim McEwan. He worked at Bowmore then… That line about people is often rolled out by marketing departments without any understanding of what it means. When I think of an Islay distillery I think of the people first, not the whisky… Speak to any of them and they all speak of the island first, why it is special. It’s in the blood, it gets under your skin.

Broom’s journey around Scotland’s whisky ends here on this windswept island, craggy like an old wizard of the sea. The people are the wizard. The peat smoke provides the wizard’s mysterious cloak—by turns ashy, briny, medicinal, conjuring beach bonfires, woodland campfires, meaty barbecues. Peated Islay whiskies are as enthralling as they are divisive, as magical as they are earthly.

It’s easy to romanticize Islay, and Scotland in general. Broom does this, without question. The very lushness of his book does this. But he is as ready to pull the rug out from under that romanticism. His poetry constantly collides with science, his metaphors with data. In his passages on Scottish oak, for example:

Oaks support over 2,300 species—birds, mammal, invertebrates, fungi, lichen, of which 326 are wholly dependent on them, and 229 rarely found elsewhere. It was the highest ranked of the seven noble trees of Irish and Scots Gaelic tradition, a symbol of strength, fertility and hospitality. Its Gaelic name—dair (Irish), darach (Scots Gaelic)—is the root of druid, and place names such as Derry. Revered though trees were, don’t imagine that early Scotland was an arboreal paradise… The felling of Scotland’s forests started in the Neolithic. Oak was useful… Many of those classically heather-clad hills are the product of logging, high-impact grazing by sheep and the explosion of deer population since Victorian times. The picturesque glens are a landscape that is out of balance.

Like the majestic oak tree, the smoky island of Islay could be reduced to its marketing. But then there are those people there. They’re working for a living and have bills to pay. There are limited resources there. Peat does not form in the ground as quickly as it is extracted by the whisky industry.

As evocative as whisky is. As many stories as its aromas conjure. As emotionally compelling as it is to the people who make it and who enjoy it. Whisky is a product, manufactured and sold for money. It comes from earth, grains, wood, water, yeast, math, science, art, craft, planning, intuition, circumstance, luck, patience, profit margins, memory, and time.

In the end, even Broom, despite his abundant eloquence, understands that words are limited. His book is packed and thick and yet does not drag on. He gets to it, weaving his core themes of place, community, and sustainability in loops that quickly add layers of nuance. But still they’re just words.

At one point Broom finds himself at Brora Distillery—established in 1819, mothballed in 1983, its dwindling derelict stocks achieving cult status in the whisky revival around 2000, and finally resurrected in 2017. Standing in one of the distillery’s old dunnage style warehouses, its original earth floor still underfoot, the air damp with generations of barrel and whisky vapors, Broom was presented with a rare pour of Brora aged 39 years. At first he does what he has practiced for so long, and lists off flavor notes. But then he catches himself:

The limits of language are revealed. What do these lists of words mean? Just give in to the sensation.

I read Dave Broom’s A Sense of Place while house-sitting for friends whose back deck has a lovely view, always with a glass in hand, and often a cat keeping me company. Not at all a bad way to spend a few evenings. I highly recommend it!

Sláinte!

Last Call

We respond emotionally to the waver, the hand of the maker. Things that are identikit take you away from that impulse, reduce the item to a product. Great music, great art… is the opposite of that. So are great whiskies. There is a signature flavour, but the finest examples play with it. They waver.