Art and whiskey share a lot in common.

I’ve made this point a few times here on the blog, specifically in relation to theater, the art to which I’ve devoted a good deal of my time and attention in life. The same basic comparisons can be made between whiskey and the visual arts as well:

Art and whiskey are handmade.

They are a craft, in addition to being an art.

They can only be fully experienced live, in person.

Some people find them intimidating, others frivolous.

Art and whiskey aren’t always easy, sometimes even dangerous. But at their best, they encourage a spirit of community, contemplation, and curiosity.

These parallels were highlighted for me again recently when I was asked by an artist and friend, Alexander Polzin, to curate a whiskey flight inspired by a collection of his work gathered for exhibition at the San Francisco branch of the German Consulate.

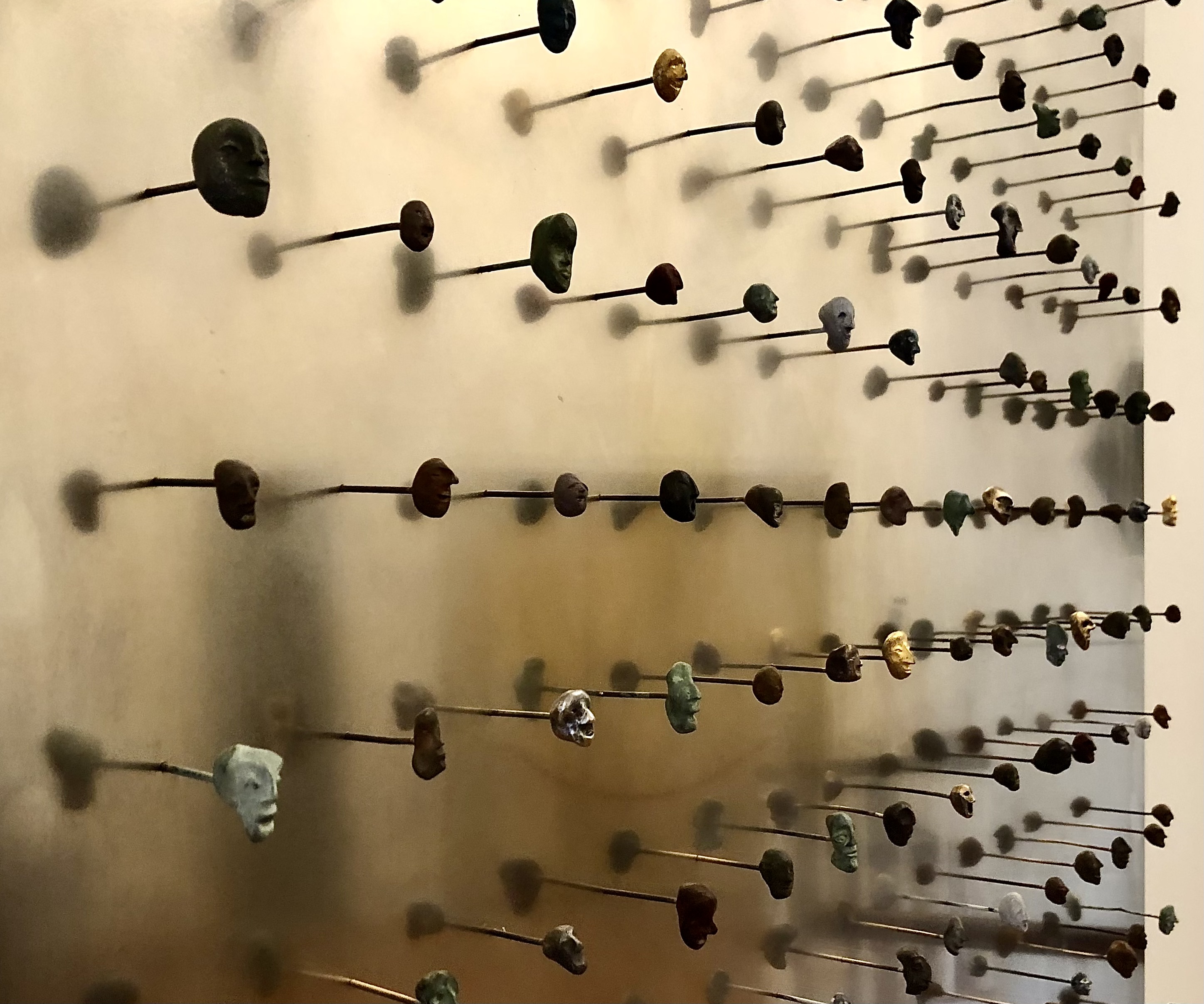

Alexander and I had had lunch in December 2022, when he was just beginning to make plans for his exhibition. We had not seen one another in several years, and in catching up we realized a shared interest in whiskey. He mentioned to me the theme of angels in his upcoming exhibition. I told him about the concept of “the angels’ share,” a reference to the whiskey that evaporates through the dense yet porous oak barrels during the aging process. Alexander liked the poetic explanation for this natural aspect of the whiskey aging process, and he decided to name his exhibition “The Angels’ Share.”

In line with this, he asked if I would curate a flight of whiskeys inspired by the art. I asked him what he would like in particular from the whiskey portion of the event. He said he wanted me to do what I enjoy.

Something I enjoy very much is the opportunity to help people new to whiskey feel welcomed by it. As with art, many people find whiskey intimidating. As with art, whiskey has a language around it. And as with art, this language is sometimes wielded by those “in the know” against those who remain as of yet still outside that know. Looking at a statue or sipping a whiskey, nobody wants to say anything “wrong” or “dumb.” They want to know what they’re “supposed” to experience so they can get it “right.” I like to offer people ways to taste and talk about whiskey that disrupt these elitist reputations and assumptions. One need not have formally studied the play Hamlet in order to enjoy a production of it, or to have even very unique insights into their experience of it. The same goes for Eagle Rare bourbon or Springbank 15 Year scotch.

And the same goes for a statue by Alexander Polzin.

I have one of Alexander’s pieces in my home, called Sisyphus. Like all his work, it is a crossroads of multiple inspirations. In the case of this piece, the myth of Sisyphus meets the life’s work of Viktor Frankl.

Sisyphus is the ancient Greek character who tried to cheat death, and as punishment was doomed by Zeus to roll a boulder up a hill for eternity—every time he reached the top, the boulder would roll back down.

Viktor Frankl (1905-97) was an Austrian psychiatrist and Holocaust survivor most known for his 1946 memoir, Man’s Search For Meaning, a controversial and illuminating account of his experiences in a Nazi concentration camp. Alexander created his Sisyphus piece in tribute to Frankl, who defined the human search for life’s meaning as highly idiosyncratic, and never ending. Alexander’s statue depicts Sisyphus as his own boulder, an embodiment of Frankl’s observation that in our personal search for meaning, we each push ourselves up our particular life’s hill only to roll back down again and again. Final meaning never comes, only the evolving search.

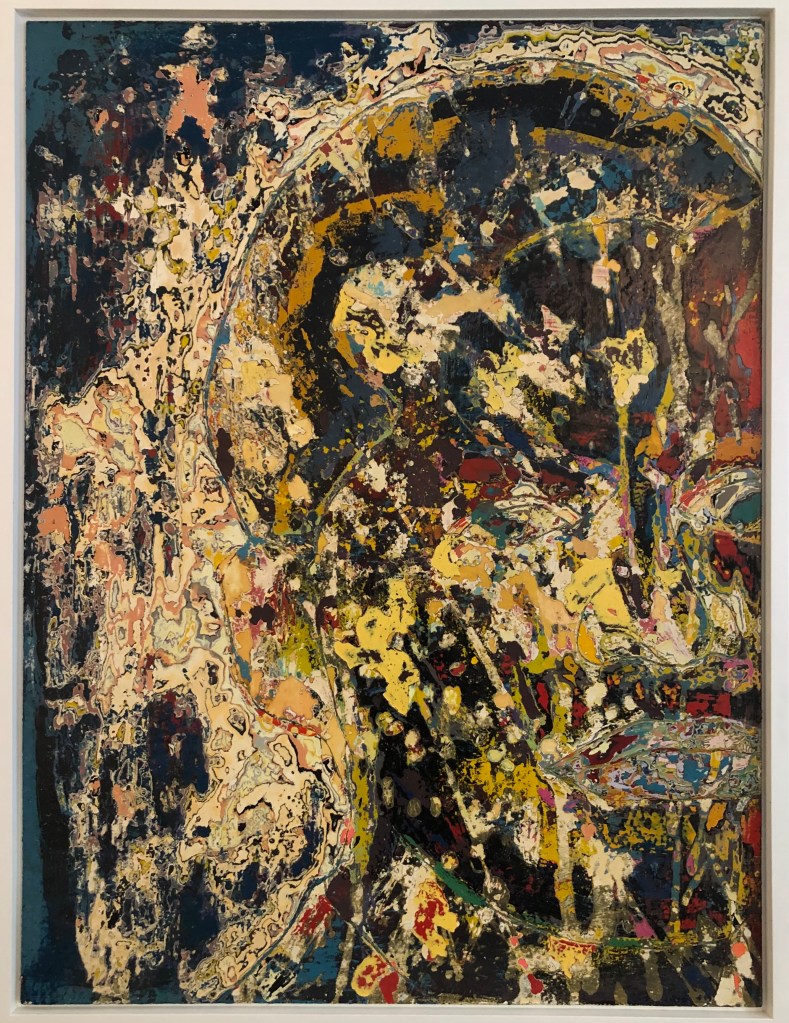

Like this example, Alexander’s series of angel sculptures do not spring only from the theme of angels. Alexander is a voracious devourer of all art forms. His statues and paintings inevitably refer to other artists who have inspired him in their own genres, and with whom he finds ongoing resonance in contemporary life—the East German playwright Heiner Müller, whom Alexander knew as a child; Dante, of The Inferno fame; György Kurtág, the Hungarian composer still making music at age 97 as I write this; Paul Celan (1920-70), the Romanian-born Jewish poet; Johann Sebastian Bach, the German Baroque era composer…

Through their art, these artists of the past hover alongside us still, like angels watching patiently as we roll ourselves up our hills and tumble back down, learning life’s lessons firsthand as we must, again and again. The necessity within a civil, thinking, empathic society for artists who document a response to history through their art—especially history’s most inexplicable emotional and psychological impacts, and in appropriately expressive ways rather than mere journalistic documentation—this necessity is eternal. Sisyphean!

How to arrange a flight of whiskeys in response to all this?

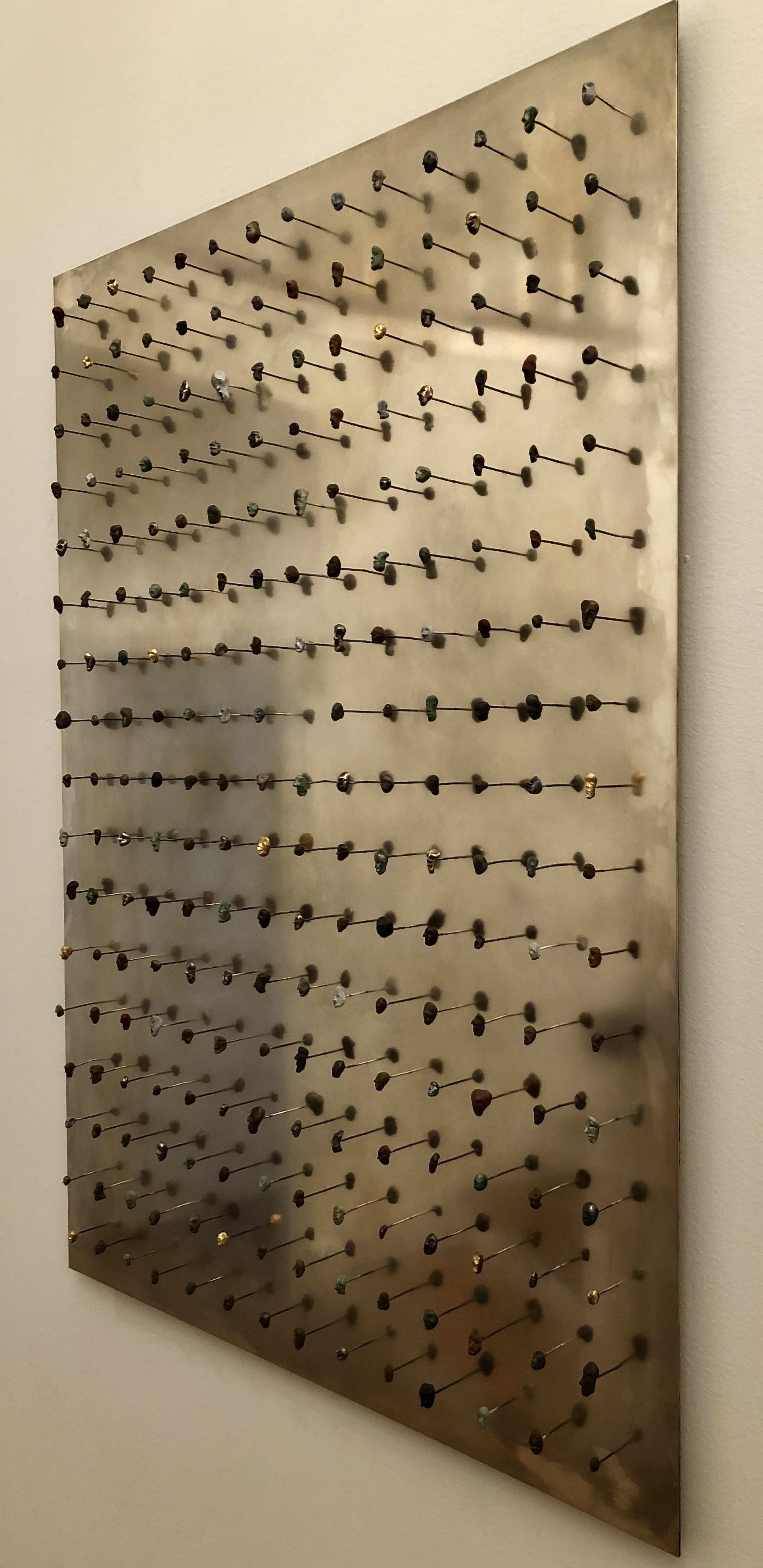

Rather than attempt to encompass Alexander’s multitude of inspirations, I focused in on the raw materials he uses—oak, bronze, gold. Alexander always carves his statues first in oak. These carvings are then bronzed, retaining the original textures of the wood, whether sanded smooth or the naturally rough ridges of their grains left exposed. Sometimes a gold or other patina is added, to capture light in some particular way or alter texture. The finished pieces retain a palpable sense of Alexander’s craftsmanship in action—metal tools shaping wood, bronze casting the effect in time. Each piece appears to still be taking shape, still evolving. And of course the art of what Alexander does is also captured—intuitive decisions made in ongoing response to his sources of inspiration, to his intention for the piece, and to what the wood itself offers in the way of texture, grain, shape, color, resistance, pliability.

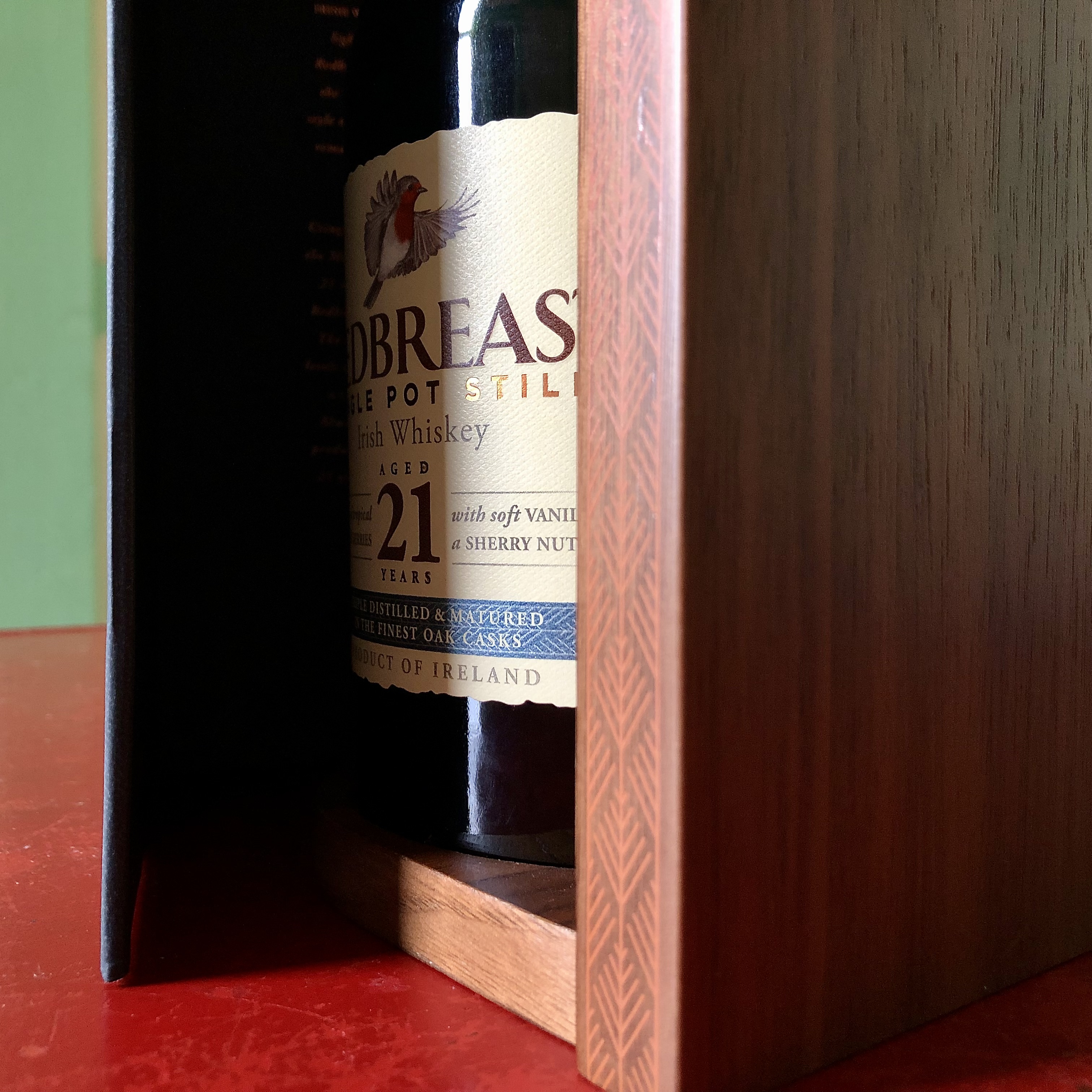

So I chose oaky whiskeys for their flavors and textures—the sweeter Eagle Rare; the dual-casked Elijah Craig Toasted Barrel and Woodinville Moscatel Cask Finished Bourbon. The bronze and gold elements of the statues led me to Redbreast 21 Year, with its metallic copper pot zing, and St. George Single Malt Lot 22, with its ringing clarity of flavors. The various rough and smooth surfaces of the pieces drew me to Springbank 15 Year, with its earthy peat notes in balance with rich red fruit notes.

At the top of the evening, after a gracious introduction to Alexander and myself by Oliver Schramm of the San Francisco Consulate General of the Federal Republic of Germany, I invited the guests to use the whiskeys to talk about the art, and the art to talk about the whiskeys. I acknowledged the intimidating reputations whiskey and art share, and that there is actually no “wrong” way to talk about either of them. I shared the meaning of “the angels’ share,” and its flip side, “the devil’s cut,” which refers to the whiskey left behind in the wood itself. I noted the key role of oak in both whiskey making and Alexander’s artwork. I only briefly went over the specific whiskeys—details could wait for our conversations.

Each guest was then given two glasses, one for each hand, Eagle Rare in the left and Elijah Craig Toasted Barrel in the right. For their third whiskey, they could come to me and we’d discuss their impressions of the first two in order to select something that might most appeal to or surprise them.

I encouraged everyone to peruse the art with their whiskeys in hand. If they felt more comfortable talking about art than whiskey, they could use the art to reflect on the whiskey. If whiskey was more familiar to them and art less so, they could use their experience of the whiskey to put words to their experience of the art.

Rather than a subdued evening of polite art appreciation, it was a boisterous event with laughter and conversation. People indeed came to me for their third pours, and were often as shy to put their experiences of the first two into words as I’d expected. But by asking them open-ended questions—What did you respond to in the Eagle Rare that made it your favorite? How did the Elijah Craig make that impression on you, was it the flavors, the aroma, something else?—people would articulate something about their experience that could help me select their next whiskey. Sometimes I sensed they wanted more of what they liked, sometimes that they were thirsty for something new. Sometimes one person would say the Eagle Rare was harsh, so they preferred the Elijah Craig, and the person next to them would turn with a start because for them it was the Elijah Craig that was harsh and the Eagle Rare smoother. So to eliminate any concern with determining who was correct, and to instead encourage a curiosity for divergent experiences, I’d then ask them both what they each meant by “harsh.” And now we were into a conversation.

It was the most fun I’d had at a tasting. Bringing two enjoyable but challenging pleasures together took the pressure off both, as well as off anyone to be “an expert,” myself included. When someone would describe a flavor they were picking up in a whiskey and ask me if that was what they were “supposed” to taste, I’d tell them they’re not supposed to taste anything other than what they themselves taste.

Of course if someone has never consciously tasted lemon zest they can’t name it as a flavor note. They might have once had lemon candies, though, and name that instead. One person might say “baking spices” and another “snickerdoodle” and actually mean the same thing. We bring our own history to our experiences, relating to our present through our memories of our past.

Same goes for Alexander’s art. If someone recognizes something of Bach’s face in the piece inspired by the composer, and if they know his music, they might reflect on Bach’s prodigious outpouring of fluid, twirling baroque compositions. If they don’t know what Bach looked like or consciously recognize his music, they might see in the piece a person bursting with ideas, and reflect on explosive creativity. Great.

For me, none of this is a matter of “to each their own opinion.” Opinions have no value—they can’t be proven nor debated, and are often used to squelch a conversation. Rather, I believe what was achieved at this art exhibition / whiskey tasting was an experience that encouraged the development of points of view. There was a process of giving attention to something—through sight, taste, and smell—sitting in that experience for a moment, then finding the words to articulate the experience and so also one’s point of view on it. Unlike an opinion, which can be born in our mouths fully formed as from the brow of Zeus, developing a point of view requires us to give attention to something outside ourselves. A point of view recognizes oneself in relation to the point viewed, and the space in between is a relationship that has the potential to shift. Finding the words is then a matter of patience, practice, and especially curiosity.

So here’s to curiosity, to art, and to multiple points of view sharing the same glass.

Prost!

Last Call

Here is a link to a BBC Radio 3 interview with Alexander, in which he shares about his range of inspirations, the impact on him of growing up in East Germany, and his work in both visual and performing arts. The interview captures well how Alexander’s work stands in a state of curious observation and reflection at a crossroads of painting, sculpture, stage design, music, literature, performance, history, and the contemporary moment.

Music in particular is a constant for Alexander. Music even served as a kind of hearth to keep him warm when he was young and working in an unheated studio in Berlin’s Pankow district. And so the interview is accompanied by a range of music, from Bach to Miles Davis.