If whiskey is “history in a bottle,” and history is essentially political history, then isn’t whiskey also politics in a bottle?

Yes, is my short answer to that question.

Any regular reader of this blog would guess that of me. I have often advocated here on behalf of the option to not leave politics at the door when gathering with friends or family around a bottle of whiskey.

I do understand that impulse, however; especially as we’ve moved deeper into the post-truth era, when there seems to be an ever more forceful inclination toward binary thinking—yes/no, friend/foe, for/against, love it/hate it, innocent/guilty, liberal/conservative… This heads-or-tales way of thinking has little to do with getting at the truth, which is always complex, or the necessarily slow and messy process of democracy.

Like most anyone else, I too have found myself in uncomfortable conversations at the dinner table on holidays. And yet (a) shouldn’t close family and good friends, whom we know well and who know us best, be ideal to talk politics with? We’re invested in one another, after all. And (b) if to not talk politics is the quiet agreement, how will we ever get better at it? Curiosity and good communication take practice. Why not practice with those closest to us and with a good glass of whiskey in hand?

To explore these questions, first I’ll lay out some examples of why whiskey is indeed history—which is to say politics—in a bottle. Then I’ll share a few basic ways I’ve learned to have meaningful conversations that are based in curiosity.

Full transparency: I am not a Communications expert of any official designation. But I have lived a good many years working in theater and education—two professions for which communication and curiosity are central. I have alternately struggled and failed and succeeded and struggled again to learn and to understand during this protracted, exceptionally conflicted period of world history. These struggles have taught me a few things that seem to work, and some that don’t. In sharing them I hope they might prove useful to others.

So if you’re still curious at this point, pour yourself a glass of something good and read on. And if you’re not curious at this point, even irritated perhaps, you might consider pouring yourself a glass of something good and reading on anyway. An adverse reaction is often as good a reason to stick with something as any favorable response.

Some Histories From Some Bottles

Whiskey has and continues to figure into the political landscape of many parts of the world. Examples of how and why this is can make great starting points for a range of conversations that go well beyond whiskey itself. Here are just a handful of examples:

Irish Whiskey

Beyond geography, the particulars that distinguish Irish whiskey from its closest cousin, scotch, came about due to economic and colonial politics.

In the 18th century, Ireland was still under the rule of Great Britain, which had been involved in several expensive wars by and around that time. New alcohol taxes were administered to help pay the government’s bills. One of these was the 1785 Malt Tax, which placed a tax on malted barley. To lessen the tax, Irish distilleries began to include non-taxed unmalted barley and other cereal grains in their mash bills. This cost-cutting measure ended up contributing to what we now recognize as the basic Irish whiskey flavor profile.

It would be another 137 years before Ireland separated itself, not just its whiskey, from the British government to become an independent nation. By then Irish whiskey’s signature mixed-grain mash bills and pot still distillation had long since been channeling the independent Irish spirit into a spirit. So a bottle of Writers Tears or Redbreast could make a great prompt for discussions of issues relating economics, colonialism and war, and how international relations play out over decades. After major events like these, what gets forgotten and what remains in the cultural memory once several generations have come and gone?

The Whiskey Rebellion

President George Washington ran a successful distillery on his property, brewing beer and distilling brandy and rye whiskey. And he wasn’t alone. Farmers across the newly established United States were distilling their excess crops of corn and rye into whiskey to sell—a profitable enterprise. Distilleries were popping up all over.

Washington’s chief aide, Alexander Hamilton, a devout temperance supporter, saw a government funding opportunity and in 1791 established a heavy tax on whiskey—not a popular move among a still new national citizenry who had fought a revolution against Great Britain largely due to unfair taxation. Hamilton argued that this tax was indeed fair, since it was taxation with representation. But in addition to economic concerns, the new tax law rose privacy concerns, as government inspectors were allowed to enter private properties at will. Protests were immediate and violent, with tax collectors getting tarred and feathered, strapped to rails and run out of town, even hanged.

and hanging a whiskey tax collector.

By 1794, with tensions still high, a majority of people impacted by the whiskey tax nevertheless did not want to enter into another war with their government. But a minority group that dubbed themselves “The Whiskey Boys” staged a violent insurgence. Shots were fired and homes burned. They demanded Hamilton recognize them by marching into Pittsburgh, PA, and claiming the city as theirs. They even wrote letters to Great Britain and Spain, proposing alliances against the United States. Washington had no choice but to respond, though the response was arguably overdone—fifteen thousand armed soldiers were sent to Pittsburgh to contain the few hundred farmers who comprised The Whiskey Boys. The Whiskey Rebellion was quickly squashed. Of the twenty insurgent leaders tried for treason, two were convicted and both of them were pardoned by Washington. The whiskey tax prevailed, and whiskey became the most popular national liquor.

The motifs and questions still relevant today are pretty clear. Objections to new taxes. An insurgence. A rebel group called “The _____ Boys.” Excessive force by government militia against citizen protests. Economics, freedom, privacy, the morality of alcohol consumption in perennial conflict with the profitability of alcohol production… Pour a glass of Journeyman Distillery’s “Not A King” Rye, pick just one item on that list, and you can likely fill an entire evening’s conversation.

Uncle Nearest

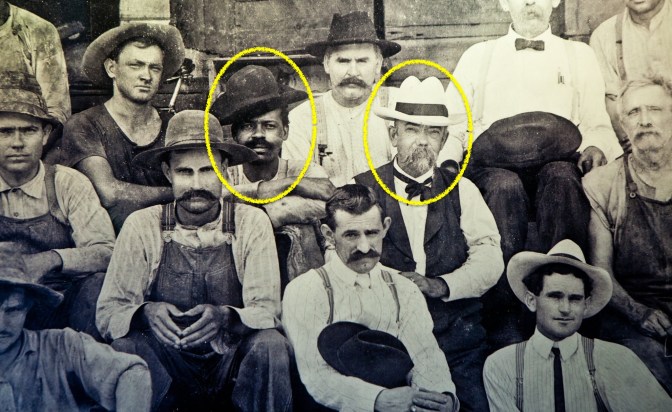

By now anyone deep into American whiskey likely knows the story behind Uncle Nearest Premium Whiskey, thanks to the tireless efforts of its founder, Fawn Weaver (above right). I’ve written about the brand and its history more extensively elsewhere. But in brief summation, the brand has done much more than add a great, award-winning whiskey to liquor store shelves. It literally corrected the history books:

In the 1850’s, Nathan “Nearest” Green, then a slave owned by a Tennessee preacher and grocer, taught a young boy named Jack Daniel how to make whiskey. It was Green, not Daniel, who introduced the West African practice of maple charcoal filtration to Tennessee whiskey making. By the time Green had been freed, Daniel had come of age and started his own distillery. He hired his former mentor to be the first master distiller of the new Jack Daniel’s Distillery.

Years later, a 1904 photo featured Green’s son, George, seated center next to a now much older Daniel. When that photo was printed in a 2016 New York Times article, it caught Fawn Weaver’s attention. Why, in the 1904 American South of all times and places, did a Black man share the central position in a company photo with that company’s White proprietor? Weaver’s pursuit of that question eventually led her to found Uncle Nearest, Inc., and its sister organization, the Nearest Green Foundation. Uncle Nearest whiskeys quickly garnered an international reputation, and the Nearest Green Foundation continues to provide historical research and scholarships for Green’s descendants.

Pour yourself a glass of Uncle Nearest and sit down with this great podcast, featuring an interview with Fawn Weaver about the Uncle Nearest brand and its history. Obvious questions arise around race, who writes history, the longterm impact of what gets emphasized and what gets left out, and how vital it is to question the historical record in order to refine our contemporary understanding of our culture and to further our ongoing attempts at democracy.

Prohibition

The popular history of American Prohibition is fairly limited to speakeasies, flappers, bootleggers like Al Capone and George Remus, and the broad notion that a minority of Americans in favor of temperance won out with politicians over a majority in favor of the freedom to drink as they pleased. There’s certainly plenty for discussion right there—the power of lobbyists in Washington D.C., the boon Prohibition was to organized crime, notions of what American “freedom” should encompass…

But America’s disastrous Prohibition experiment is actually one part of a larger global movement dovetailing religious, progressive political, and colonial concerns, with key players as varied as Vladimir Lennin, Mahatma Gandhi and Ida B. Wells taking active part. Beyond the backroom speakeasies and an American citizen’s “right” to mix cocktails, Prohibition taps into broader issues like the relationship of freedom to responsibility, religious and political ideological conflicts, the inequity of citizenship along race, class, and gender lines, and the systemic national and international oppression of the economically poor and especially of peoples of color.

So pour yourself a glass of Remus Repeal Reserve or Old Forester 1920 and watch Ken Burns’ excellent documentary, Prohibition, or crack open Mark Lawrence Shrad’s book, Smashing the Liquor Machine: A Global History of Prohibition. Then consider what has and hasn’t changed since that time. American Prohibition is not just a charming chapter of deviant history set to the Charleston. The range of issues it bubbles with still swirl in our present day lives.

@BeckyPaskin

In September 2020, British spirits journalist Becky Paskin (above) posted a series of tweets condemning author Jim Murray’s annual self-published Whiskey Bible for his frequently misogynist reviews. Paskin asked very pointedly why the whiskey industry continued to condone Murray’s annual book? An article in Forbes asking similar questions coincided with Paskin’s social media posts. Shortly after, the New York Times followed up. The whiskey world took notice quickly. A number of brands put out statements in solidarity with Paskin’s condemnation of Murray’s—and the industry’s—ongoing sexism.

Predictably, there were men who objected to Paskin’s objections. In doing so, they often only underscored Paskin’s points about how women have been treated by men throughout the spirits industry, and in the work place generally. Many of these objectors used the same sexist language Paskin had called out, and many also declared whiskey no place for gender-related or any other politics.

More recently, Rachel MacNeill of the Islay Whisky Academy, a women owned and operated whisky appreciation school based in Islay, wrote a short opinion piece questioning Paskin’s choice to single out an individual. Did this allow distilleries to scapegoat Murray, rather than properly acknowledge and apologize for the longstanding sexism under their own roofs? Did the attention brighten Murray’s arguably fading star, rather than allowing him to fade out on his own outdated irrelevance? What’s the ratio of progress to polarization resulting from a social media driven debate like Paskin’s?

The whiskey industry’s long history of fostering a masculine image, a kind of worldwide “boys club,” is undeniable—if one favors verifiable and objective facts. It’s difficult to imagine anyone not recognizing that any individual is merely one example in a larger, deeply entrenched system of gender discrimination. Why do women still have to do the labor to educate men on this? This might be an interesting question to discuss over a glass of Home Base Whiskey or Purpose Rye.

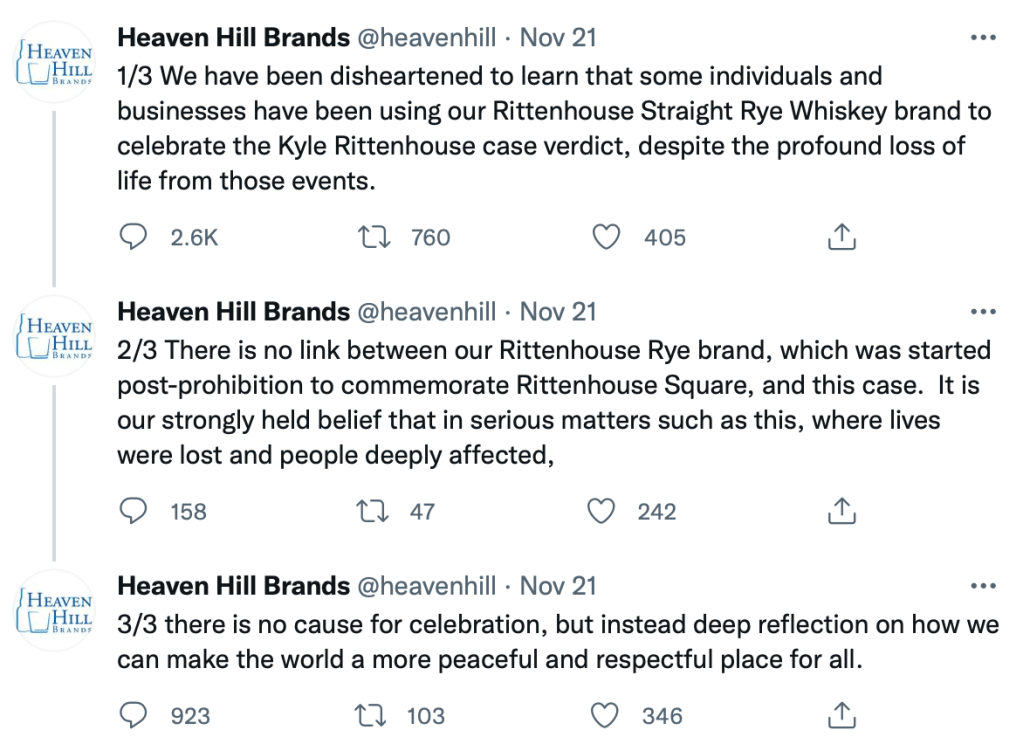

Rittenhouse

When Heaven Hill tweeted an acknowledgment that their rye brand, Rittenhouse Bottled in Bond, was being used by some people to celebrate the verdict in the 2021 Kyle Rittenhouse trial, the comment stream that gushed beneath their tweets was as predictably binary as one might expect from social media—people commending Heaven Hill and others denouncing them.

Many among the latter expressed disapproval that a whiskey maker would acknowledge a political event in relation to their whiskey—a bit of a hypocrisy by anyone who themselves had politicized Rittenhouse Rye in using it to toast the verdict. And though Heaven Hill actually did not state a position on the verdict itself, but only recognized the trial as a serious and important matter involving the loss of life, this recognition was enough to elicit every cliche social media retort one need not try even very hard to imagine. One Tweeter even implied Heaven Hill was asking for it for having named their product “Rittenhouse” in the first place, despite the obvious point, which Heaven Hill had already made, that the brand name has been around since Prohibition—decades before Kyle Rittenhouse was born.

But social media has never been a forum requiring even basic research, much less critical thought. Rather, it demonstrates the extent to which the American people value reactionary opinion over considered response. So here we have people politicizing a whiskey due to the coincidence of its name, then denouncing the distillery as “too political” for acknowledging their product having been politicized. Beyond whiskey and Kyle Rittenhouse, what might this phenomenon suggest about our national culture of democratic debate?

Talkin’ Politics

In just this handful of examples—and there are many more—the range of issues include some of the most perennially challenging to grapple with: racism, sexism, colonialism, nationalism, what “freedom” means, what makes a healthy democracy… None of these are issues we ever finish working on. They need our ongoing attention, our vigilance and our generosity of spirit. If we’re honest we must admit we don’t always give them that.

Because it’s not easy! Yet if a person chooses to end their journey with these things, they do so at their peril—and in doing so put into peril anyone who must deal with them. In the long run, the hard work of prioritizing our curiosity over our conclusions surely must be worth the effort, if we hope to get along well together.

The obvious difficulty comes from these political matters being extremely personal—not distant at all, but intimately close. Coursing through the material flesh of our blood and bones are things far less tangible, and arguably most important to us in the end: our identities, our emotional and psychological perspectives, our sense of wellbeing and safety, our memories and the memories of ancestors we’ve never even met yet we feel them with us.

So it absolutely makes sense to me that anything truly important is hard to talk about—perhaps especially with the people we care about most. The ultimate inadequacy of words shows itself in these conversations. Words can be powerful. They can also be slippery and carry multiple meanings not understood equally by everyone using them.

So what to do when these hard subjects come up at the table and won’t go away? In addition to pouring a glass of something strong and pleasing, here’s a brief outline of one simple physical practice I’ve found helpful to start with:

- When I feel my emotional heat rise, rather than speak I take a long slow breath.

- Next, I listen. When again I feel the urge to speak, if I’m still feeling the heat, I breathe instead and keep listening.

- And I mean actually listening. Clear signs that I’m not actually listening: I interrupt someone. I formulate my comeback in my head while they’re talking. I wait for them to stop talking, which is not at all the same intent as listening while they are talking.

- To listen well, I must do nothing else, physically or mentally. Just listen—not to respond but to understand.

- Further toward understanding, before sharing my own point of view I prioritize asking the other person questions about their point of view.

- I must be honest with myself that my questions are actually questions, not statements disguised as questions, or, worse, clever traps!

Now that’s all pretty easy to write. It is harder to do in practice. I fail at it all the time. But as I’ve learned in theater, it helps to practice. Imagine showing up on opening night of a show, never having rehearsed. The classic actor’s nightmare!

Again, I’m not an expert in these things. I’ve learned from people who have taken the time and devoted the energy to developing their expertise in communicating, like the people behind the Center for Nonviolent Communication. I won’t attempt to sum up their invaluable work here. But in their own words, here’s a concise introduction:

The Center for Nonviolent Communication is a global organization that supports the learning and sharing of Nonviolent Communication (NVC), and helps people peacefully and effectively resolve conflicts in personal, organizational, and political settings…

NVC begins by assuming that we are all compassionate by nature and that violent strategies—whether verbal or physical—are learned behaviors taught and supported by the prevailing culture.

NVC also assumes that we all share the same, basic human needs, and that all actions are a strategy to meet one or more of these needs. People who practice NVC have found greater authenticity in their communication, increased understanding, deepening connection and conflict resolution.

There’s an imperative here not only for curiosity but also its close cousin, empathy. Among NVC practices is a very simple response formula, which can feel restrictive at times yet provides a useful framework to practice communicating effectively around emotionally challenging subjects.

This formula is explained very well in an essay published online by BayNVC, a cousin organization of the Center for Nonviolent Communication. There they outline some core components of NVC: Observation, Feelings, Needs and Requests. Put into the language formula of a statement, these might look like this:

When you [say, do, etc…] ….

I feel …..

because I need …..

Would you be willing to …..?

An observation is offered. A feeling that arises in response to what was observed is articulated. The need that creates the feeling is named. And finally a request is made or suggested. An example might be:

When you interrupt me I feel frustrated because I need to know you value what I have to say. Would you be willing to hold back when you feel the impulse to interrupt me?

The person on the other end of this may choose to grant or deny the request. But notice they have not been accused of anything. They have not been verbally attacked. By prioritizing empathy over aggression, the chances of them responding in kind, though not guaranteed, are more likely.

Communicating in this way also helps the person making the request keep their own heat in check. The emphasis is shifted from things like winning an argument, or shutting the other person down, to curiosity.

Formulated into a question, the offer might look like this:

When you [see, hear, etc…] ….

are you feeling …..

because you need …..?

And would you like …..?

An example might be:

When you hear me say I want to slow down and take more time are you feeling frustrated because you need to finally get to the bottom of this? And would you like for us to brainstorm together some more concise ways of getting there?

Asking a question likewise puts the emphasis on empathy. Perhaps the other person is struggling to articulate what they are feeling and needing. By offering them a possible articulation in the form of a question, one may or may not succeed in naming their feelings and needs, of course. But now they have something to respond to, and they might be better able to articulate for themselves.

These formulas are deceptively clean and tidy. They don’t always work and sometimes need adapting. But they can help us in a charged conversation to put our feelings and needs into clear words. Nobody hears our feelings, after all. They hear our words, which are our attempt to capture what we feel. These linguistic formulas provide a model to riff on. They are a place to start.

A fun, low-risk way to practice these principles might be to arrange a whiskey tasting with someone in which each brings a bottle they know the other does not care for, but which they themselves love. A flight of contentious whiskeys! The evening’s goal would not be to determine which whiskey is objectively “best,” or, worse, to agree to disagree—which is only ever an utter failure to communicate. Rather, the flight’s purpose would be to get to know one another better by exercising curiosity. Why do our friends and family like what they like, and not like what they don’t? What do they value in a whiskey—taste, region, history, price, prestige? Why? What do they need? How do their values serve those needs?

Why we do, or do not, care for a whiskey can be a starting point for a conversation about larger things. Want to have that hard conversation about race with your family? Bring a bottle of Mixed Blood Blended Whiskey to share. Want to have a more productive conversation about an upcoming election? Plunk a bottle of Madam Whiskey or Jefferson’s Reserve on the table. Start with the whiskey, then lean into your curiosity and stay there—especially when it’s not the ABV but what people are saying that’s upping the heat!

There are many things one might gain from pouring a bit of history in their glass.

Cheers!

Resources

The 18th-Century Tax That Shaped the Future and Identity of Irish Whiskey – concise Vinepair article outlining the complexities of the 1785 Malt Tax.

BayNVC essay outlining the basics of nonviolent communication.

Black Bourbon Society – bridging the gap between the spirits industry and African American bourbon enthusiasts through social media, live events, and info sharing.

Center for Nonviolent Communication – global organization that supports the learning and sharing of nonviolent communication.

Decolonizing Non-Violent Communication – book by Meenadchi, Co-Conspirator Press, 2018.

Drinking Buddies: Jack Daniel and Nearest Green – great podcast interviewing Fawn Weaver about the Uncle Nearest brand and its history.

Drinking In America: Our Secret History – book by Susan Cheever, Twelve / Hachette Book Group, 2015.

Every Ounce a Man’s Whiskey? – well-researched article by Seán S. McKeithan about bourbon’s complex relationship to personal and cultural identity.

Manly Men Versus Vodka Sodas: The Gender Baggage of Booze – thoughtful article by Emily Saladino on the gendering of alcohol.

New York Times article on accusations of sexism in Jim Murray’s Whiskey Bible and the spirits industry.

Nonviolent Communication: A Language of Life: Life-Changing Tools for Healthy Relationships – book by Marshall B. Rosenberg, PuddleDancer Press, 2015.

Our Whisky – global campaign championing diversity and inclusion in the whisky industry through online events and info sharing.

Prohibition – three-part documentary by Ken Burns, Public Broadcasting System, 2011.

Sexism In Whisky: Why You Shouldn’t Read The Whisky Bible – Forbes article on Jim Murray’s Whiskey Bible and sexism in the spirits industry.

Smashing the Liquor Machine: A Global History of Prohibition – book by Mark Lawrence Schrad, Oxford University Press, 2021.

Trauma-Informed NVC – An approach to NVC developed by Meenadchi, emphasizing an awareness of trauma-response, transformative justice, and decolonization.

Whiskey Rebellion – History.com article summarizing the history around the 1794 Whiskey Rebellion.

You’re Not Listening: What You’re Missing And Why It Matters – book by Kate Murphy, Celadon Books, 2019