“Dusty” is a term colloquial to the whiskey fan community. What does it mean exactly? And what’s “a dusty” worth?

“Dusty” in whiskey-speak is no pejorative. Ageism works in reverse when it comes to whiskey. The older the better!

Supposedly.

“Dusty” is slang, not a legally defined term. In short, it refers to a whiskey bottled and released in the past. There is no recognized authority determining what number of years ago a whiskey must have been bottled and released to qualify as “a dusty,” though roughly ten years would seem to be the generally accepted minimum. Even that is a purely anecdotal estimate. But suffice to say, whiskey fans are perennially intrigued by the dusty past!

What’s the big deal about some old bottle of whiskey that’s been languishing on some shelf or in someone’s basement? If dusties are so intriguing, why did they go so long un-bought or unopened?

Many possible reasons. It could be a common or a lesser known brand. Could be grandma bought it and forgot. Maybe it was well regarded when it came out and whiskey fans hoarded cases. Maybe it got lost in the corner of a corner store’s back room.

As for worth, assuming we’re talking dollars, the capitalists are correct that the value of any whiskey, whether dusty or shiny and new, is whatever people are willing to pay. Yet amidst that subjectivity, a couple of objective factors determining the worth of dusties have nevertheless settled in over time:

First, with each decade you go back in time, the price of a dusty will go up. Second, a brand that is widely sought after today, like Wild Turkey or Weller, will command higher prices on the dusty market than something generally disregarded like Ancient Age or High Ten. Put these two objective factors—era and brand—together and the subjective price is determined. Any brand from the Prohibition era or prior, of course—regardless of whether it’s well-known or entirely forgotten—is dusty gold!

However a dusty came to knit its shawl and for however long, still, why the fascination? Whiskeys aren’t like art or antique furniture. One can display them as objects. But ultimately they’re a product made to be consumed. And that a whiskey was bottled ten or twenty or fifty years ago, and distilled some five to twenty years earlier, does not at all guarantee it will be good. It might even taste terrible!

But ☞ provided the cork has remained tightly sealed, uncorking a whiskey today that was distilled and bottled in some past era is as close as human beings can get to experiencing time travel.

This is because, unlike wine, whiskey remains unchanged in a properly sealed bottle. Chemical reactions between the alcohol, water, distilled grains and yeast, and oak influence, are all on pause for lack of oxygen to incite them. Only when a whiskey is uncorked and once again in contact with air do its molecular chain reactions resume. (Even that scientific fact is rejected by some whiskey fans, who insist an open bottle of whiskey does not change. Of course, some people also still think the earth is flat. 😉)

Sipping a whiskey from the 1970s or 1930s, we are consuming water, oak, grain, and yeast preserved from another time. This physical contact, like the whiskey’s own fresh contact with open air, immediately sets off more chemical chain reactions. For some finite period of time, something of the past is indeed present. And as we drink it, that past becomes a part of us in the here and now. We are literally touching history.

That’s the cosmic level of our fascination with dusty whiskeys. On a more grounded level, we’re curious. We know how whiskeys taste now. How did they taste then?

This basic curiosity can in turn prompt reflections. What was life like in one past year or another? Rougher? Smoother? Sweeter? More bitter? Curiosity grounded in aroma and taste gives way to memory, imagination, and the philosophical. Dusties can take us on a variety of journeys.

“Dusty” vs “Old”

One more clarification before we go on some journeys.

As noted, key to “dusty” status is the year a whiskey was bottled and released. So, as I write this, a 2024 release of Elijah Craig 18 Year is not a dusty. If it makes it to 2034 it will be. But upon its release it’s just old.

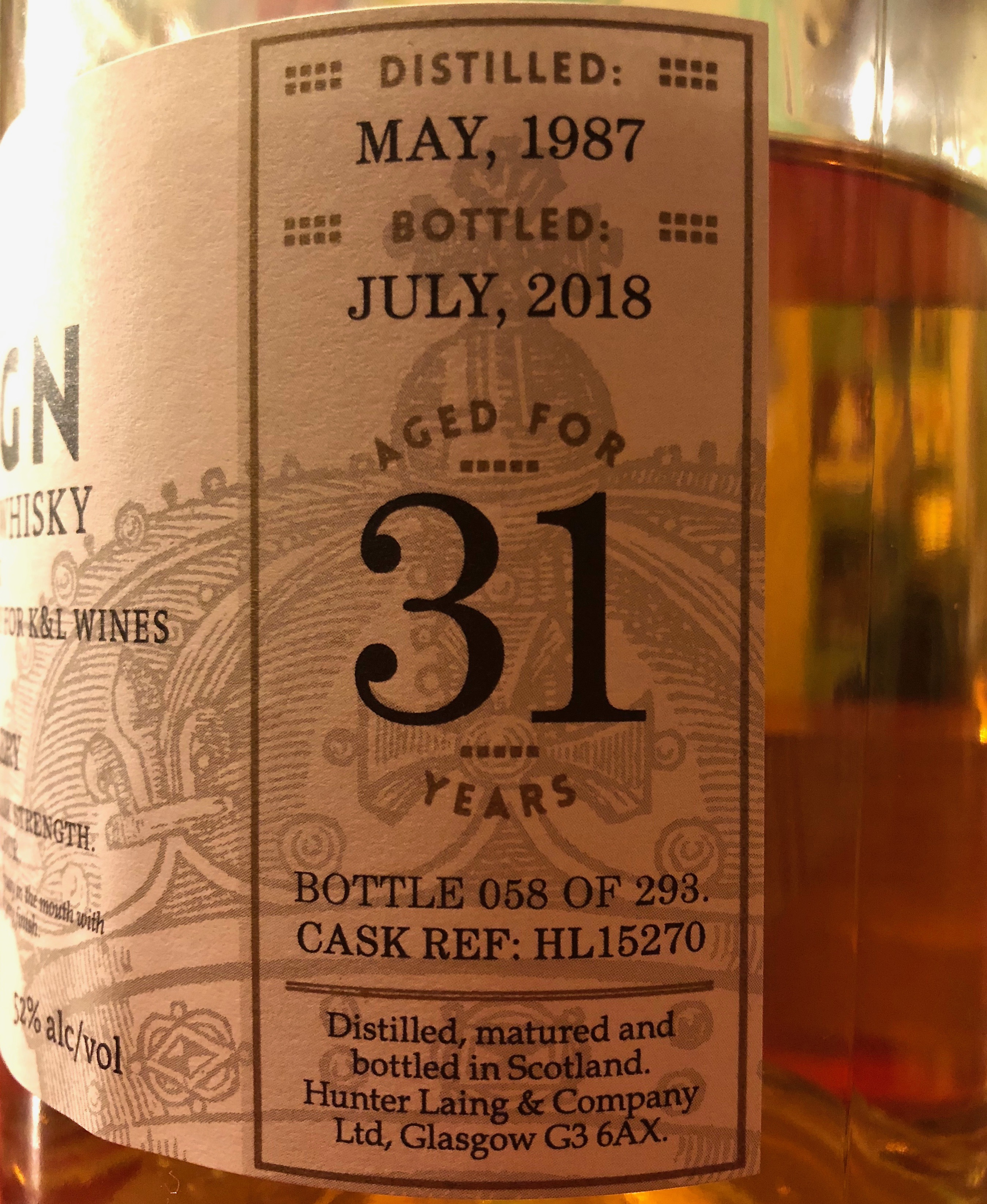

When it comes to scotch, however, “dusty” and “old” arguably dovetail. Scotch involves far older age statements than American bourbon and rye tend to do. Because scotch is aged in used barrels, there is a greater possibility for it to age well beyond the point that a new oak barrel would render a bourbon or rye unbearably woody.

So, not only might one come across a scotch bottled and released decades ago, on top of that it might also have aged in its barrel for 30+ or even 50+ years. And yet a scotch bottled yesterday that was aged for 30 or 50 years was still distilled in a very different time than the present. Can it count as a dusty?

As with American bourbons and ryes, older and/or dustier scotch does not guarantee better scotch. But sometimes it can very well be. So for the consumer it’s a kind of gambling. There’s fun, risk, and the potential for reward.

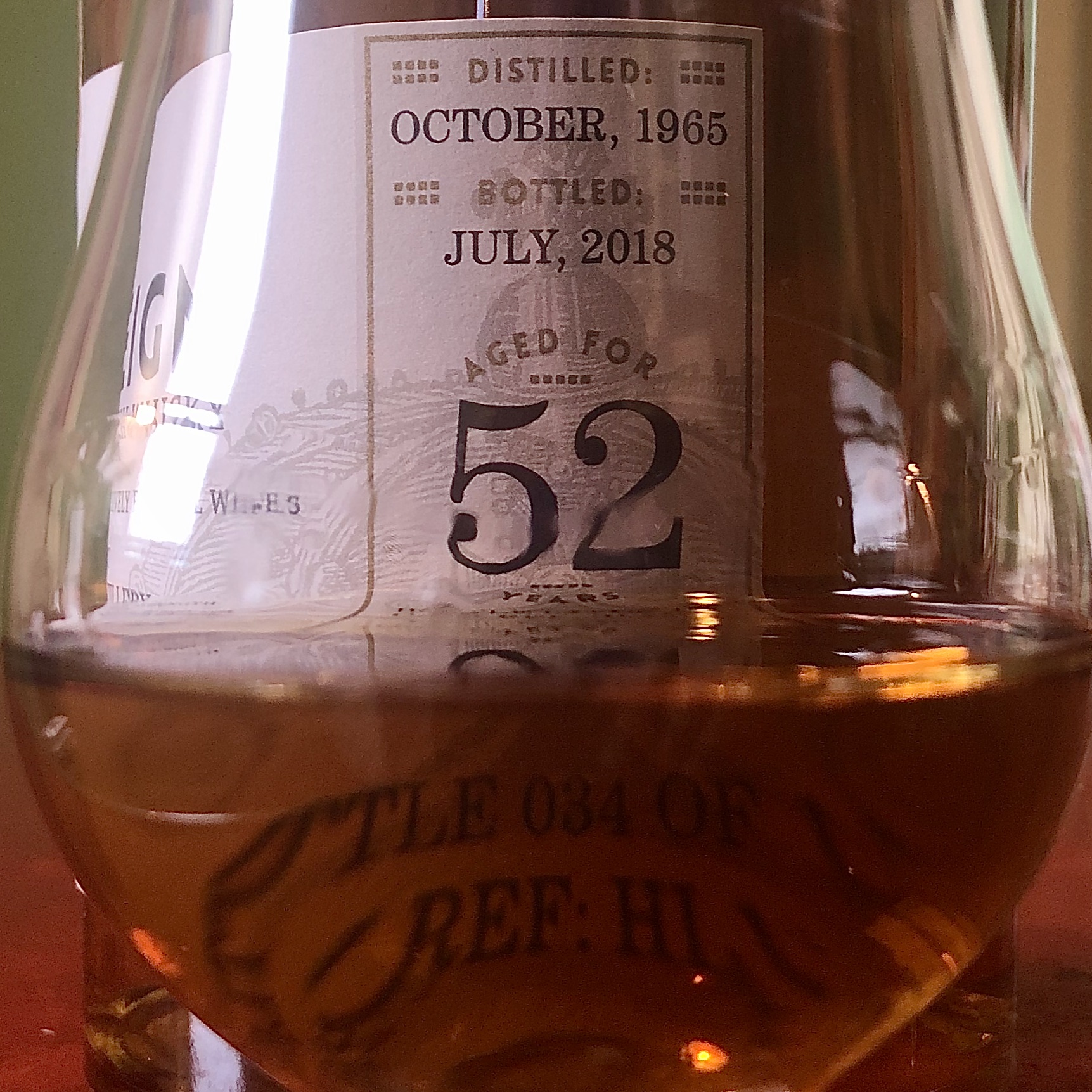

I had a Carsebridge 52 Year Single Grain Scotch, distilled in 1965 and bottled in 2018, that to this day remains among the most genuinely unique whisky experiences I’ve ever had. Turkish figs, golden raisins, Riesling, honeyed caramel, savory spices like cardamom, turmeric, and cumin. Simply amazing.

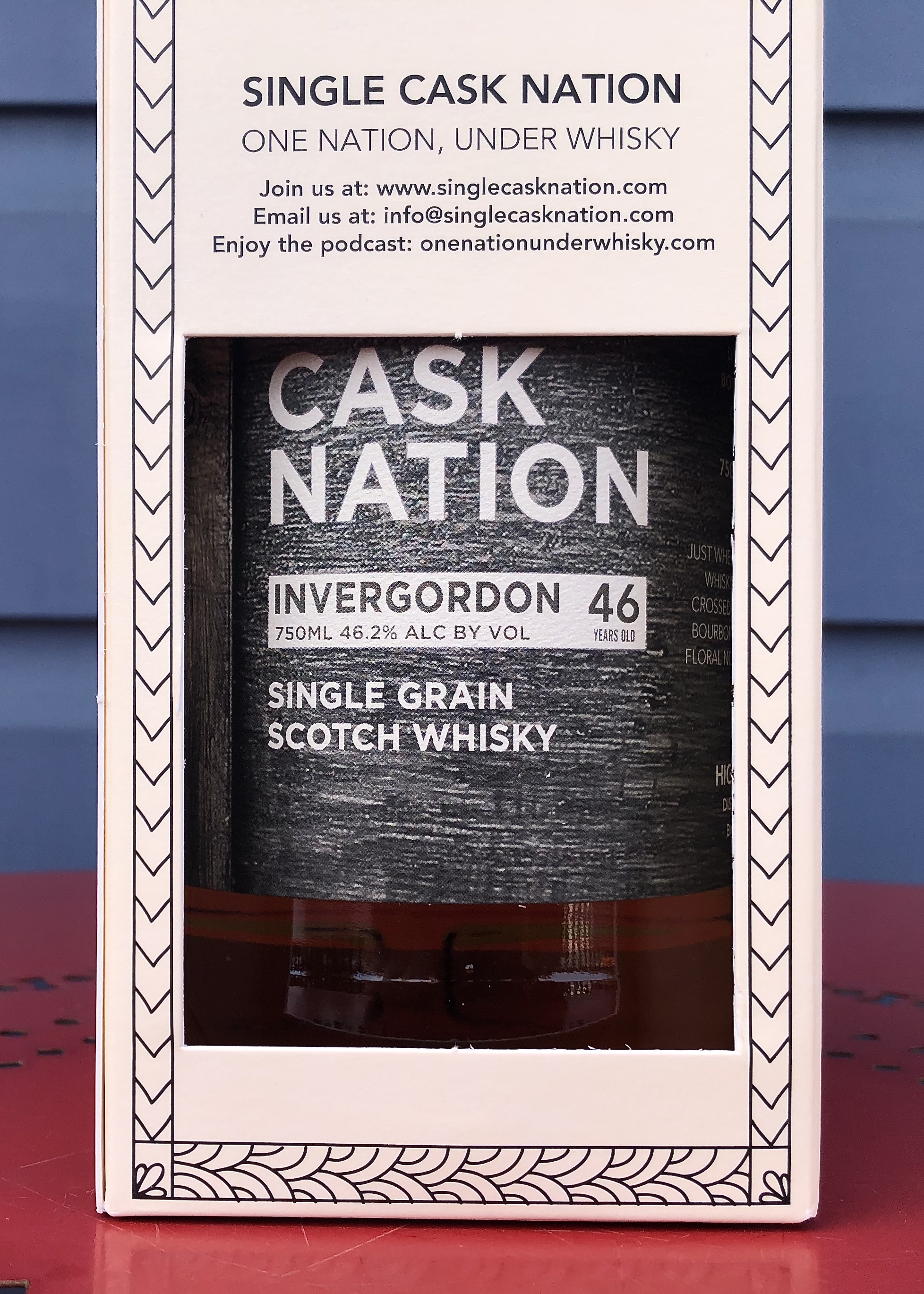

By contrast, an Invergordon 46 Year Single Grain Scotch, distilled in 1974 and bottled in 2020, was fine. Not bad. Just fine. Very familiar scotch notes of lemon, vanilla, caramel, tropical fruit, and salt. I paid only slightly less for this bottle than I had done for the Carsebridge 52 Year. But in this case I did have a touch of buyer’s regret.

Once the money’s gone, of course, it’s gone. No use bemoaning it. But having experienced three Invergordon bottles ranging in age from 46 down to 29, I know I don’t enjoy the general flavor profile enough to invest in that distillery any further. On the other hand, should I ever encounter another Carsebridge at any age, and the price is in the vicinity of what I’ve paid before, I’d go for it. I’ve had only two Carsebridge bottlings—that 52 Year and a 40 Year, itself distilled in 1976 and bottled in 2016. Both were exceptional. So the odds that I’d like whatever third bottle I encounter are good—not guaranteed, but good.

These are a whisky gambler’s considerations. 🏇🃏🎰🥃

Some Dusty Journeys

Okay. We’ve defined what a dusty is, and the blurred line between “dusty” and “old” whiskeys. Let’s go on a few journeys back in time along the ol’ dusty trail…

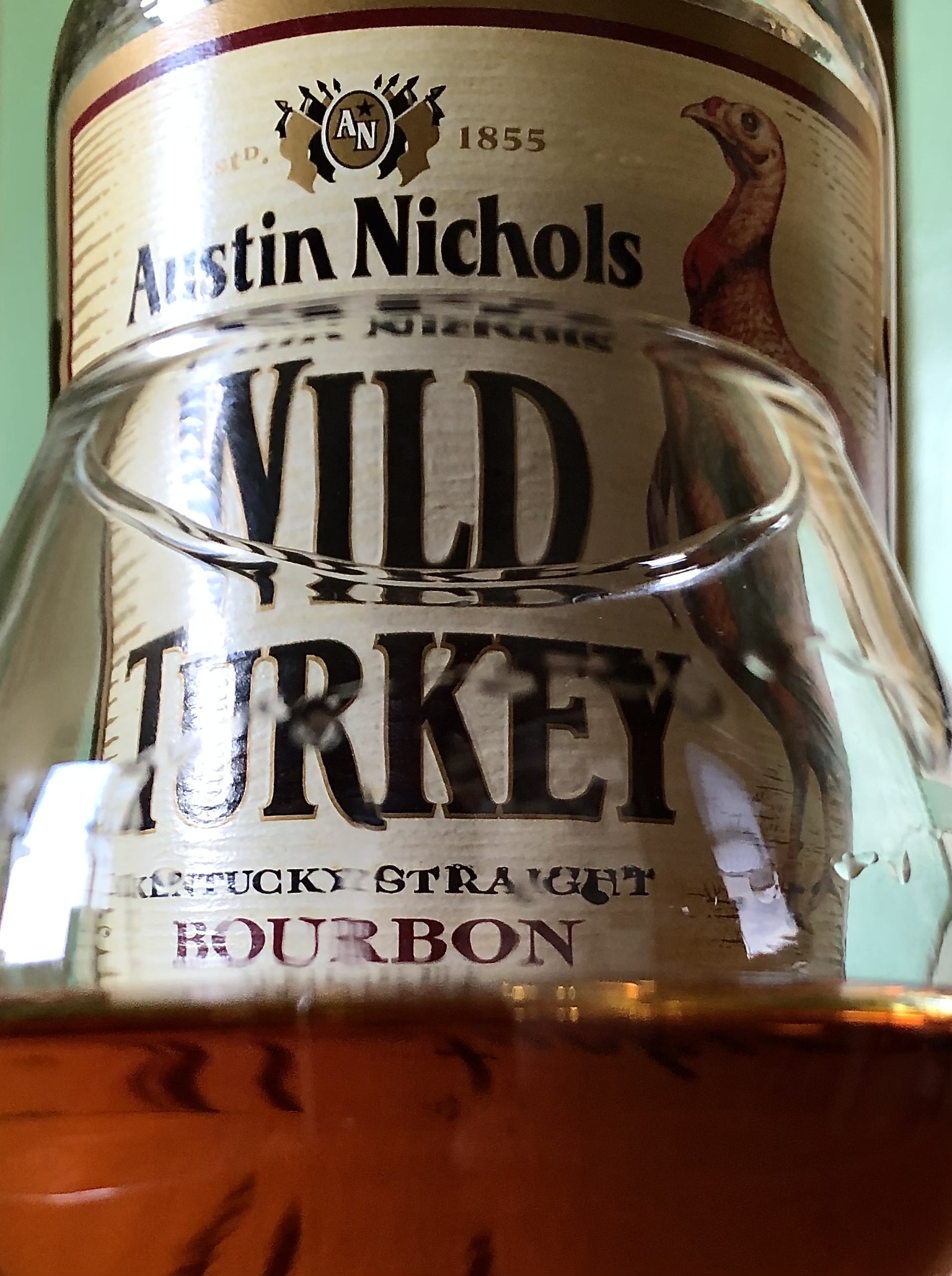

WILD TURKEY

King of the Dusties?

Wild Turkey dusties are among the most sought after among American bourbons. Current Wild Turkey 101, the distillery’s classic bottom-shelf product, is ~$25 on average. A Wild Turkey 101 from the 1990s might now cost you ~$600 if you’re lucky. A bottle from the 1970s will easily top $1000.

But these prices have to do with more than number of years sealed on the shelf. It’s known that Wild Turkey bourbon originally went into the barrel at 107 proof. This lasted for decades. Then in 2004, the entry proof was raised to 110, and in 2006 to 115, where it has remained since. Lower entry proofs mean good things for flavor, since the final product need not be watered down as much to get to the desired bottling proof. So they quite literally don’t make Wild Turkey like they used to.

There are other factors too, of course, for why a dusty Wild Turkey might taste different. Were the distillation pipes cleaned less often or differently back in the day? Were they still using the old cypress wood fermenting vats? The quality of oak was different—the wood of oak trees cut today is less dense than it used to be. And we know our fresh water supplies are dwindling by the year, as we continue to dump our many innovations and other excesses into streams, rivers, and oceans, undeterred by signs that the planet is not happy with “human progress.” All of this impacts taste.

As of this writing, the oldest Wild Turkey I’ve personally tasted was a 2001 bottling of Wild Turkey 101, a rustic bourbon joy distilled some time in the 1990s. But it was in 2020 that I found the most interesting Wild Turkey dusty I’ve experienced: a bottle of Wild Turkey Forgiven Batch 302.

Forgiven was a short-lived brand extension born out of an accident—an employee mistakenly dumped some rye into a vat of bourbon. But Eddie and Jimmy Russell made the best of it, and in 2013 put out a special release of a more refined attempt at their employee’s mistake. So the bottle I found had been sitting on the shelf of a small town liquor store for seven years, untouched by anything but dust. Still tagged at its original msrp, this was whiskey geek gold! I bought it.

When I finally uncorked it two years later, the uncorking made a satisfying pop, air swooping into the whiskey for the first time in nearly a decade. An odd aroma hit my nose immediately, something like spoiled raw chicken meat. Oh no!

It was not good. After letting it sit in the glass for a long while, the raw meat note lifted a bit. The nose now showed more classic Wild Turkey cherry, amidst a funky herbal mildew note, some cinnamon stick, cinnamon hard candies and gum. The taste had lovely dark cherries and light baking spice—much better than the nose, though not terribly complex and with a fairly thin texture at 91 proof. The finish was all black cherry syrup, fading warmly.

Weeks passed and Forgiven remained a funky pour. That awful raw fowl note had dissipated. But I could sense its shadow among the dark cherry and funky mildew notes.

This was a key learning experience for me. If a whiskey has not breathed air for a significant number of years, it makes sense that its first gasp of the present may naturally be a bit of a chemical shock. With time, change should not be surprising, and will hopefully be for the better!

🥃

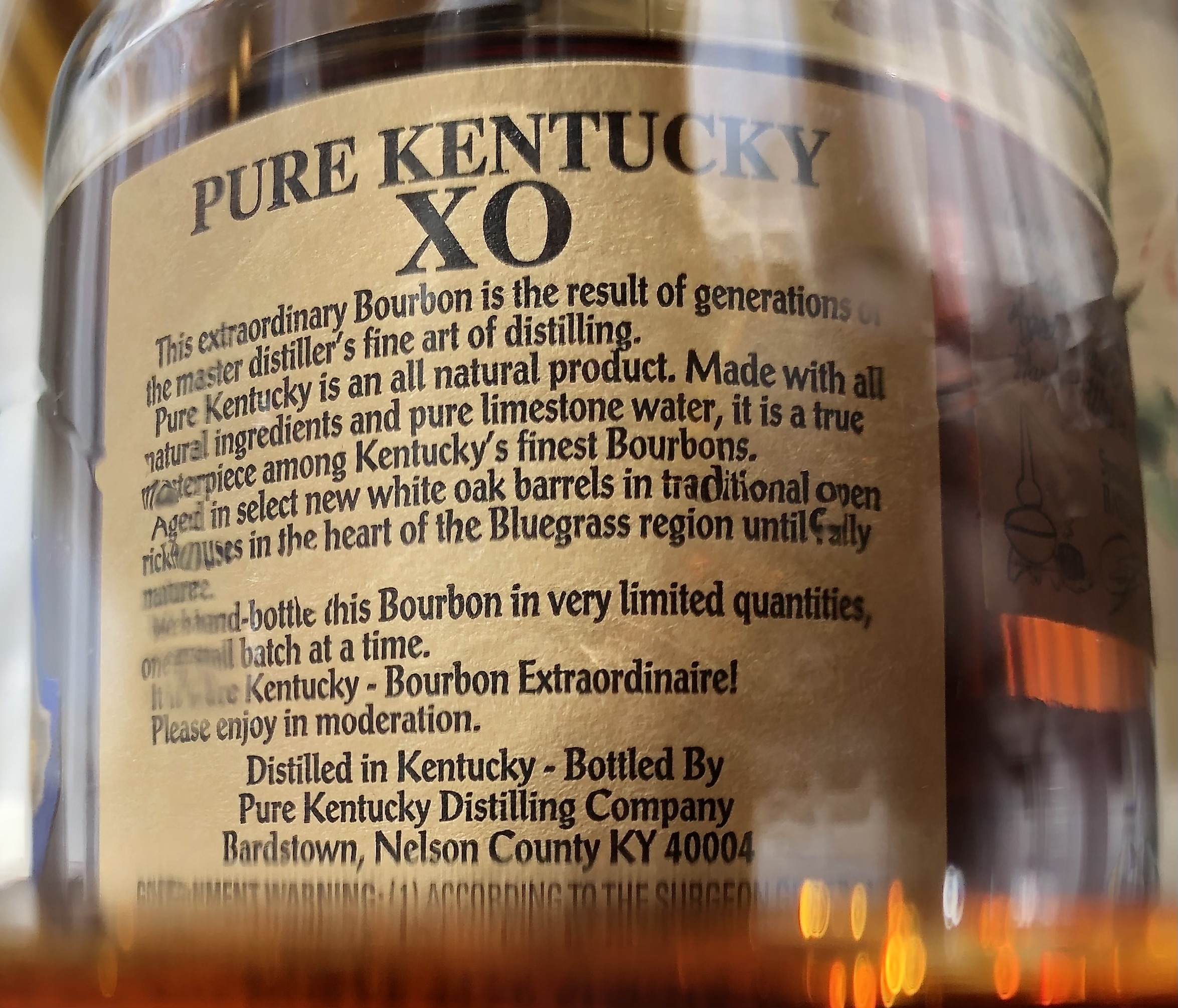

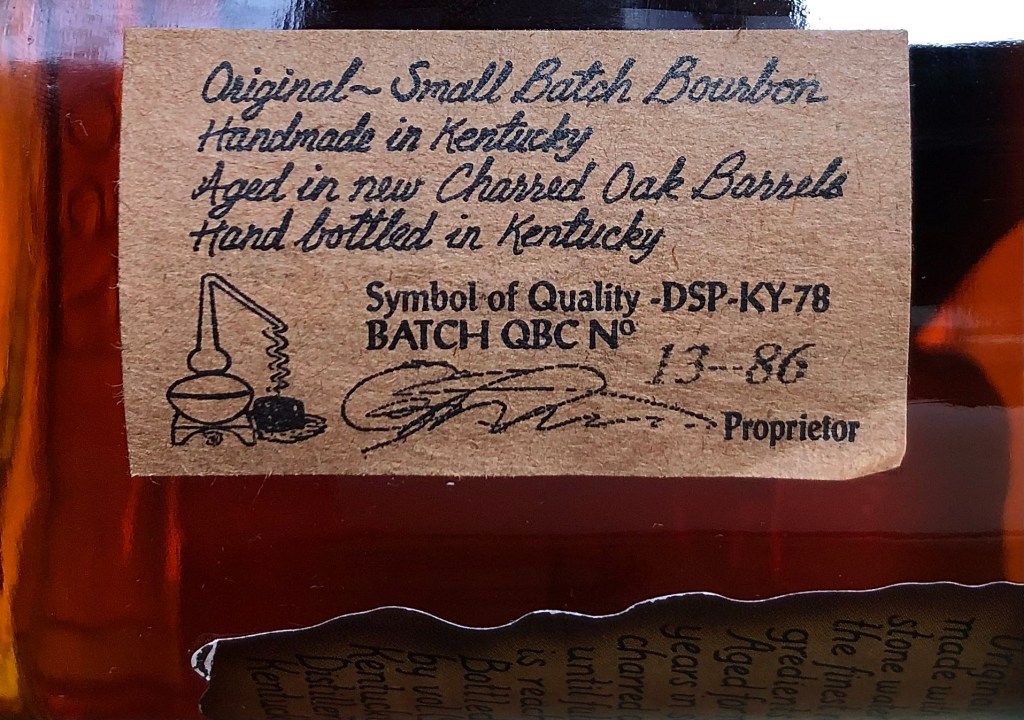

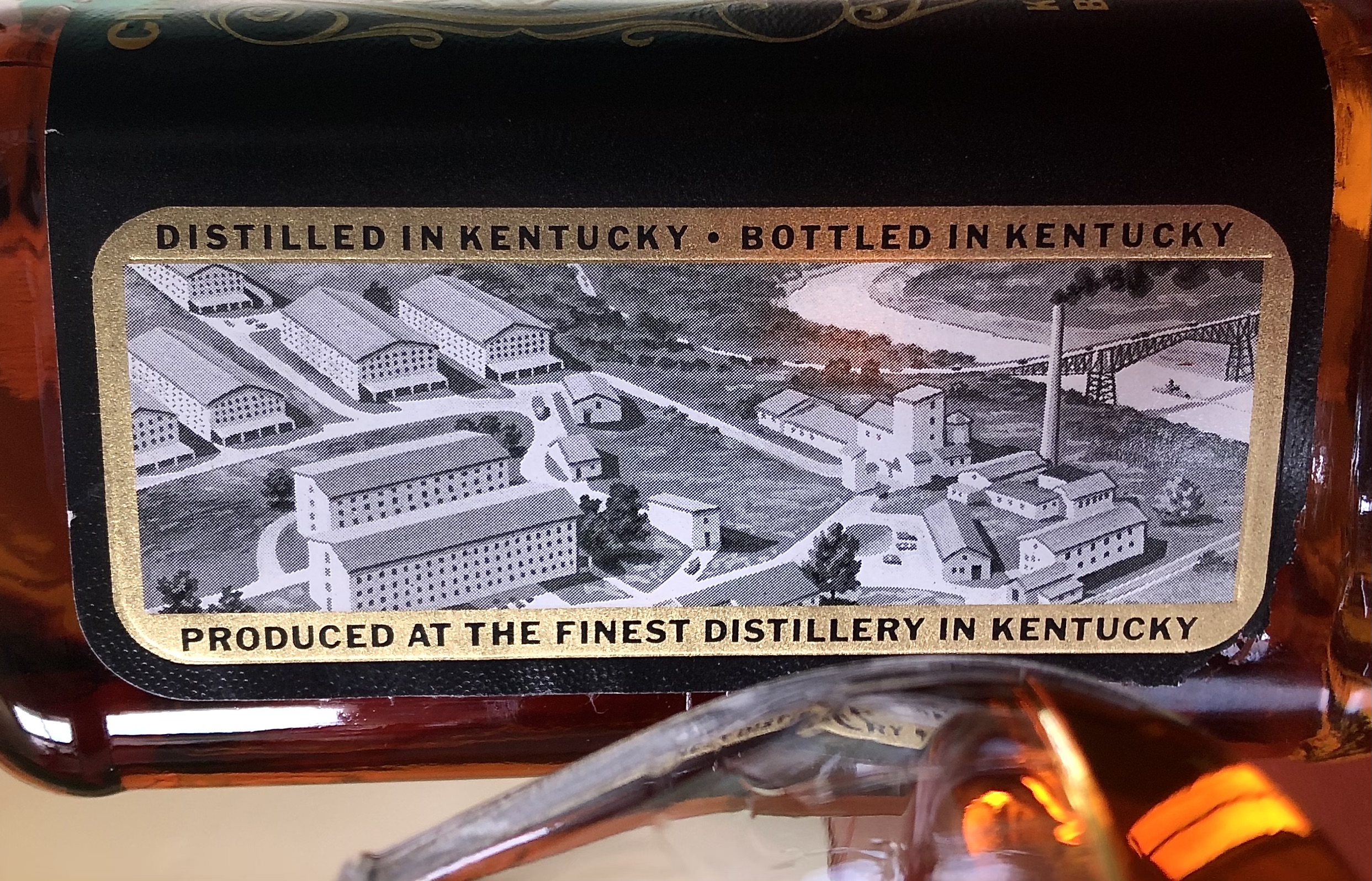

KENTUCKY VINTAGE

I quite recently uncorked a 2013 release of Kentucky Vintage. I’d found it a few weeks before, cloaked in dust as thick as wool, on the shelf of a local corner store.

Kentucky Vintage is a brand owned by Willett. In 2012, Willett began to distill their own whiskey. Until then they blended and bottled a range of sourced whiskeys, reportedly from MGP, Heaven Hill, Jim Beam, Barton, possibly others. So a 2013 bottle of any of their sourced brands would still contain 100% sourced whiskey.

By 2013, Willett had long since removed age statements from their sourced brands. Pure Kentucky XO and Rowan’s Creek were both originally age-stated at 12 years. Noah’s Mill and Johnny Drum once had 15-year age statements. (Though Kentucky Vintage never had an age statement, its label claims it “has been allowed to age long beyond that of any ordinary bourbon.” This of course means nothing.) It behooved Willett to drop age commitments in favor of wider blending options, and to ease customer expectations toward the in-house direction they were heading. It worked. Today, their in-house Four Year Small Batch Rye is a modern classic among ryes, with higher-aged single barrel releases fetching much higher prices.

I bought the 2013 Kentucky Vintage hoping to get a taste of what Willett used to blend into a standard release among those they founded their reputation on. Tax and all, I paid $38 for it, so, the stakes weren’t that high. And based on a fairly recent flight of 2016 and 2017 sourced Willett products I’d done, where none were particularly good, I knew not to expect much. Still, my whiskey geek optimism had me crossing my fingers that 2013, just one year after Willett commenced distilling their own stuff, might mean good things! Or at least better things.

At uncorking, I found the Kentucky Vintage immediately off-putting. The nose opened with an unpleasant mildewing funk, red wine residue left in the bottom of an empty glass, cheap cinnamon, vanilla, and peanut. The taste was very consistent with the nose. The finish followed suit, re-emphasizing that funk. Not a good bourbon at all. Remembering my Wild Turkey Forgiven experience, however, I crossed my fingers that the Kentucky Vintage would improve with air. Having been asleep for eleven years, maybe it just needed some time to wake up…

Returning to it ten days later, tasted in a traditional Glencairn, here are some formal notes in brief:

COLOR – a smooth pale russet orange

NOSE – cinnamon and confectionary sugar on toast, dry sweet grasses, herbal / mildew funk, sarsaparilla and cola, faint Jiffy peanut butter

TASTE – the Jiffy peanut butter comes on strong, backed up by the funk; there is the texture of the spices without their taste (strange)

FINISH – leaves a gritty texture, with the funk and Jiffy, a bit of the cola, something like cardboard, and finally an unappealing bitterness lingering longest

OVERALL – Nope

I’m stubborn, so I’ll give this a third go in another couple weeks. But I’m not hopeful. It’s certainly better now than at uncorking. The funk is not as insistent anymore, which helps. But with zero fruit notes and only a thin bit of sweetness from the sugar and mainstream peanut butter aspects, it’s rather boring. And then in the end, when that unappealing bitterness sets in, it has overstayed its welcome and now it’s just annoying.

And that’s the gamble.

🥃

ANDERSON CLUB 15 YEAR

In 2023 I opened a 2005 bottle of Anderson Club 15 Year that was distilled by Heaven Hill in 1990. That’s a thirty-three year time span from distillation to uncorking. Today, bourbons aged 15 years are priced at a premium without question. But this 2005 Anderson Club was designed as a cheap bottom-shelf Japanese export, not sold in the United States.

Fate, however, rendered it a sought after “dusty.” You see, in 1996, Heaven Hill famously caught fire. Millions of barrels went up in flames, along with the distilling equipment. Following the disaster, distillation was exported to neighboring distilleries until Heaven Hill could rebuild and resume in-house operations. Though many barrels of whiskey were lost, those that remained were the last to be distilled on the original Heaven Hill equipment. And that’s a circumstance and story that no dedicated bourbon fan can resist. Yell “pre-fire Heaven Hill” in a crowded room of bourbon geeks and you’ll have their rapt attention.

I bought my 2005 bottle of Anderson Club 15 from an online operation in the Netherlands. Shipping it from Europe was cheaper by far than what I’d pay for the same bottle anywhere in the United States. Still, it was expensive. Anticipation was great. Pre-fire Heaven Hill!

It tasted like cheap bottom-shelf bourbon—in other words exactly what it was. There was indeed a funkiness to it, something herbal and quite plastic. But also a wide range of other notes, like baked cherry pie with thick flaky crust, drizzled vanilla caramel, cream soda, chocolate cake with cheap caramel frosting, roasted mixed nuts, dry oak cut for firewood, old fashioned orange flavored hard candies, baking spices. And all of this within a surprising syrupy texture, despite the thin cheap quality to many of the flavors.

So, not a great bourbon. But not a bad one either. A good experience overall, with a definite sense of tasting history. I did not regret my purchase. But the experience demonstrated to me that I can afford to be very choosy should I ever wish to plunk down a high price for yesteryear whiskey again.

🥃

Last Call

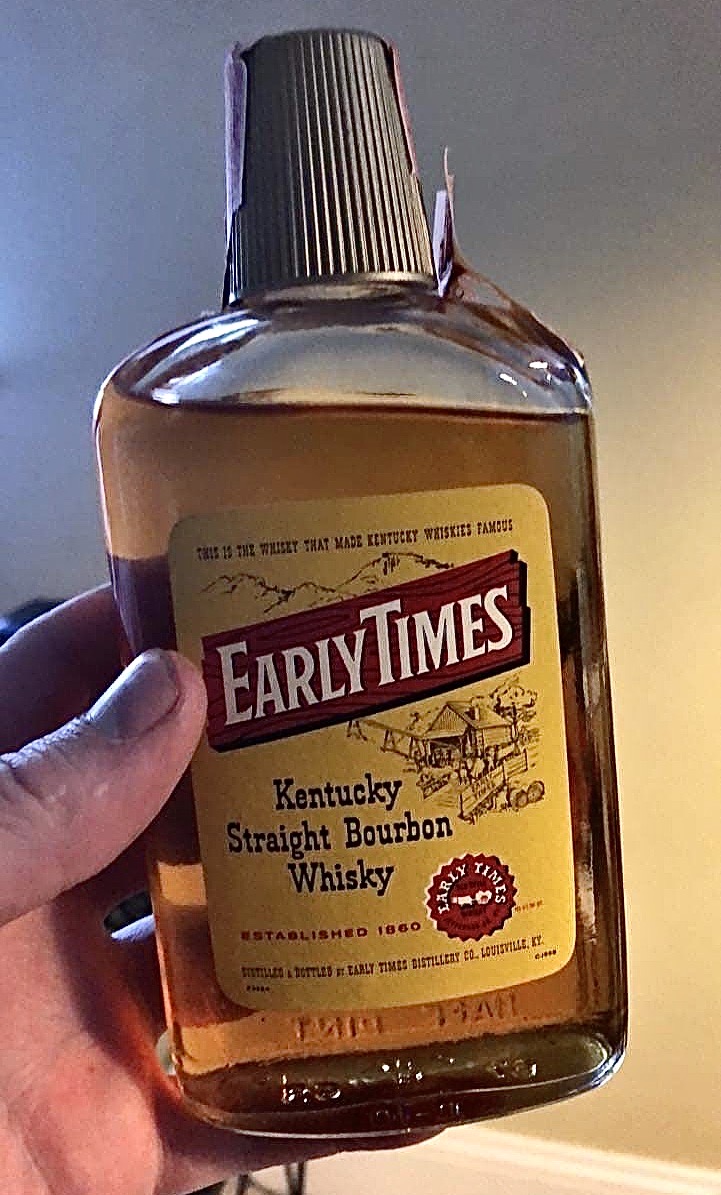

Sipping a sample of 1970s Early Times a fellow whiskey fan gave to me, I reminisced about my first decade of life—those sepia-toned 1970s with their weary forced optimism after the disillusionment of Watergate and Vietnam, not to mention the world-wide violent explosion that was 1968 and the several assassinations and uproars leading up to it. As a kid I didn’t understand that greater context. But my formative brain clocked a certain plastic quality to all the sweet smiles on TV. That 1970s Early Times sample had that same sweet plastic quality about it.

Sipping a 2016 release of Jefferson’s Presidential Select 20 Year in 2023 with an old friend I’d met in 1996, the year the Jefferson’s was distilled, we talked about those three years—1996, 2016, and 2023. High points and low points. How the world had changed and so had we. The sense of freedom and D.I.Y. creativity of the late 1990s. The utter shock of the 2016 presidential election. Being out of the pandemic in 2023 yet still feeling its seismic reverberations. The bourbon was excellent, as was our evening of catching up. Good old friends and good old bourbon pair very well.

The unique flavor profile of an early High West Rendezvous Rye blend. The earthiness of a Booker’s from the brand’s “masking tape” label days. Old bottlings of classic brands like Elijah Craig or Wild Turkey. Even unique attempts to recreate flavor profiles of the past, like Rare Character’s Fortuna revival experiment. All of these variations on the “dusty” phenomenon provide opportunities for curiosity. There’s never a guarantee you’ll like them. But you can pretty well depend on something interesting arising out of those old bottles—a memory, a bit of history, a journey in time.

Cheers!