Whiskey is a movie character that’s had a lot of screen time.

Whiskey is the Horatio to cinema’s many Hamlets. By this I mean “Hamlet” as whichever main character we’re to follow, and, as in Shakespeare’s play, Horatio as the lead’s unconditional friend—trusted, agreeable, present when desired.

Whiskey makes for a particularly brooding Horatio, of course. It’s a toxin, after all. And yet whiskey has no aspirations to cause harm. It passes no judgment, neither against itself nor those of us who drink it. Whiskey simply is. So, Horatio—companion to all who care to embrace it, in whatever way they do.

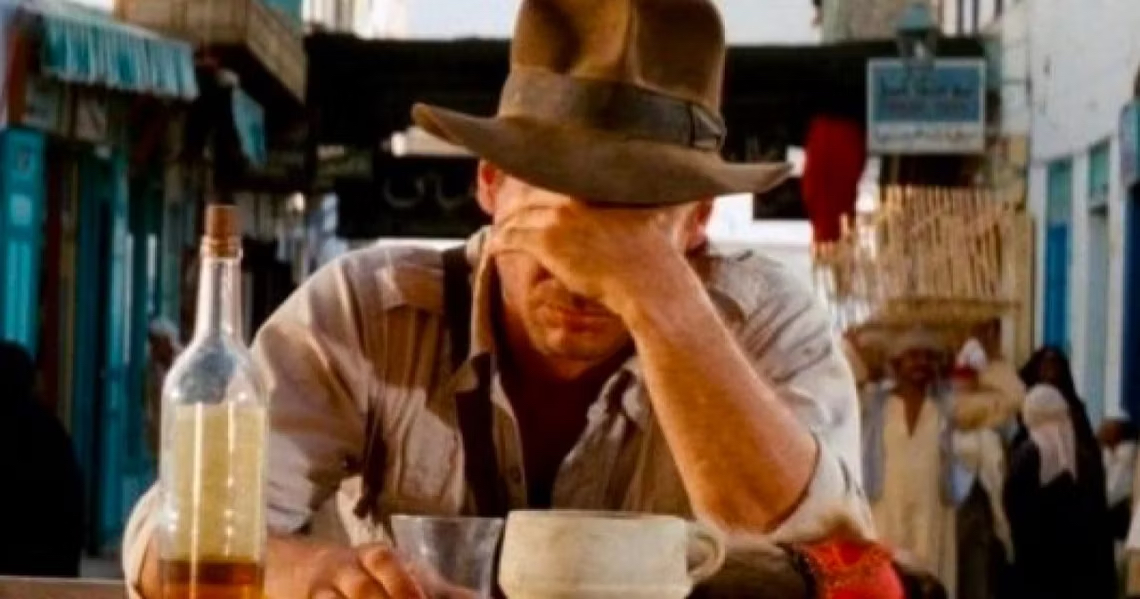

Many films show their characters only incidentally drinking whiskey, usually in some troubled moment. These are nearly always men. George Bailey contemplating suicide in It’s A Wonderful Life (1946). Indiana Jones after he believes Marion has died in Raiders of the Lost Ark (1981). The title hero of John Wick (2014) nursing a pour of Blanton’s while nursing his wounds. They sip at a glass in their moment of upset, then cut to the next scene and get on with the plot.

If a female lead character is featured drinking—not just whiskey but anything—it’s usually not incidental. It’s alcoholism. Martha in Who’s Afraid of Virginia Woolf? (1966) Wanda Wilcox in Barfly (1987). Gloria in Colossal (2016). Certainly there are movies depicting male alcoholics—Days of Wine and Roses, Leaving Las Vegas, A Star Is Born. But the dearth of women characters shown having a whiskey in passing, only in addiction, is notable. Whereas men in movies would seem more often able to handle whiskey as an occasional indulgence. 🤔

The gender baggage of booze is certainly something worth its own blog post.

In any event, whiskey seldom appears in cinema’s celebratory scenes. A glass of whiskey inevitably punctuates struggle. Occasionally it makes an appearance as the elegant ally, the cool companion. But it’s most often there as Hamlet’s questionable confidant, a consort who’s not really helping, merely numbing. Momentarily soothing, ultimately not good, a bit player in any case.

And yet in some films, whiskey takes on a role slightly more complicated than this dominant cliché. Still enigmatic. Still an amber screen on which we and the given Hamlet may project our own interpretations. But somehow more specific and meaningful than a habitual shot tossed back in a passing downcast moment. A lasting impression is made. When we remember the film we may likely remember the whiskey, too.

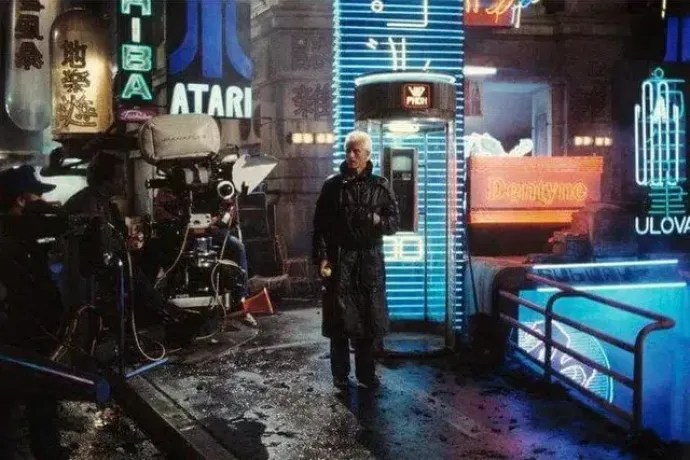

Blade Runner

Director Ridely Scott’s 1982 dystopian classic, an enigmatic and philosophical sci-fi detective story set in an imagined 2019 Los Angeles, remains a master class in creating a complete 360-degree world through the innately visual language of cinema. The film features a myriad of images that are now instantly recognizable, and infinitely quoted by other films.

In the movie, Harrison Ford as the detective, Deckard, drinks his nightly pour of Johnnie Walker Black from a very specific glass: a Cibi Old Fashioned Tumbler. It’s a testament to the glass’s designer, Cini Boeri, that Blade Runner fans picked her glass out from the onslaught of complex visuals for which the film is so famous. Every shot in Blade Runner is packed with design, from clothing to architecture to street signs to common household appliances. But it’s this whiskey glass that continues to sell to this day. The company that makes it, Arnolfo Di Cambio, even refers to it as “the Blade Runner glass” in some of their marketing, granting the glass its own separate website. Cini Boeri’s name is of course far less familiar, despite the many achievements of her long career.

Despite its futuristic setting, Blade Runner is very much in the tradition of twentieth century American detective noir. Ford’s character, Deckard, is the eponymous Blade Runner, a detective who specializes in tracking down and “retiring” (the film’s euphemism for killing) escaped Replicants, genetically engineered humanoids designed for slave labor. Deckard’s recurrent whisky helps us understand both his function and character. Whether used to relax after showering off the day’s blood, or sipped as accompaniment to sorting through evidence related to his case, the whisky in its tumbler instantly marks Deckard as the hardboiled detective. A loner. His hope protected by a veneer of cynicism. His demons gnawing at his aspirations. The physical and emotional toll of his work assuaged by Horatio—in this case a full glass of Johnnie Walker Black.

The 2017 sequel, Blade Runner 2049, features a new detective in the lead, dubbed only “K,” who also drinks whisky after each brutal day on the job. K eventually meets Deckard in a vacant Las Vegas resort, where Deckard’s been living in hiding. After their violent first encounter, the two Blade Runners sit down at the derelict hotel’s bar to share a glass. With this gesture the film tells us they accept one another, without either of them having to say so. The ritual of sharing whisky unites hardboiled detectives across generations. Deckard even shares some with his old dog, signaling they too are equals—a telling character detail.

Lost In Translation

Sophia Coppola’s 2003 Lost In Translation is set in Tokyo, Japan, the key aesthetic inspiration for Blade Runner. Take a walk around Tokyo’s present-day Shinjuku district and the sights and sounds will remind you instantly of Deckard and K’s beat.

Although both films share a theme of loneliness, Lost in Translation strikes a very different tone. But perhaps it is the loneliness that made whisky such a natural fit for the plot’s opening event: fictional middle-aged American film star, Bob Harris (played by Bill Murray), shooting a Suntory Whisky commercial in Japan.

It’s not uncommon for American celebrities who don’t do commercial work in the US to do it for the Japanese market. Even big stars. Harrison Ford appeared in Kirin Beer commercials in the 1990s. Around that same time, James Brown did an ad for Nissin Cup Noodles. Audrey Hepburn appeared in a 1970s series of ads for Varie, a Japanese wig manufacturer.

We know that Hepburn, Brown, and Ford all did very well for themselves in their artistic careers. There’s a reason big stars didn’t want to do commercials that would run in the US. It carried a stigma of failure, something that “D-List” stars, no longer in demand, might do out of financial necessity.

That stigma has certainly lightened in recent years, with perfectly wealthy megastars like Nicole Kidman and Natalie Portman doing multiple US-aired commercial ad campaigns. But that vague connotation of fallen stars remains, and this residual dust adds a layer to our understanding of Coppola’s lead character, Bob, facing his midlife crisis. His being in Japan to do a Suntory Whisky commercial is a dual sign of both his successes and failures. The fact that what he’s selling is whisky stirs loneliness into that complex duality.

Coppola’s lighting of these scenes reinforces the whisky’s role. The dull amber wash tinging everything gives a sense that the whole setting is as weary and troubled as the jet-lagged, life-lagged Bob.

When not on set modeling whisky for Suntory, Bob can be found drinking whisky at his hotel’s bar. This is where he meets the film’s other lead, Charlotte (Scarlett Johansson), lonely in Tokyo for reasons of her own early-life crisis. These scenes are also dim and awash in whisky-amber light—only more saturated now, offering hope for a brightening of our leads’ mutual dull malaise. It’s not until they hit the town together that Tokyo’s dazzling and surreal range of neon/digital color starts to signal a shift for them. Tokyo’s colorful pallet lights their growing friendship. Yet still there is a dulling florescence tempering everything we see, grey like the mist of condensation on a cold glass, reminding us Bob and Charlotte are followed on their karaoke bar hopping adventures by those grey quandaries they hope to escape.

So while whisky’s screen time tapers off rapidly once Bob and Charlotte hit it off, still its mist hangs in the air around them, the bitter to their momentary friendship’s sweet.

The Shining

Whiskey is certainly not always the congenial companion to crusty detectives and lonely hearts. Sometimes whiskey seems to drop Shakespeare’s Horatio to play Goethe’s Mephistopheles—that world-weary devil who wishes humanity would finally become humane and put him out of business.

Stanley Kubrick’s 1980 cinematic take on Stephen King’s novel, The Shining, features Jack Nicholson’s iconic hammy turn as a mediocre writer, Jack Torrence, who takes a job as the custodian of a remote mountain resort that’s closed for the winter season. The gig requires his wife and son join him. They live alone in the labyrinthian high-end hotel, surrounded by a bleak wilderness blanketed in thick snow.

As they all go stir-crazy, Jack goes actually crazy. His visits to the hotel’s glamorous, empty bar gradually summon spirits. Alone, he slumps his face into his hands and says, “I’d give anything for a drink. I’d give my goddamn soul…” And Mephistopheles takes his cue.

When Jack looks up from behind his hands, there is the bartender, Lloyd. The empty bar shelves are now well stocked. Jack either pours himself—or is served by Lloyd, the ghost of bartenders past—a glass of Jack Daniel’s. Or maybe even the whiskey is a ghost. Jack notes it’s his first drink in five months. And in one sip, the whiskey pulls even more evil to Jack’s surface than was already evident.

At one point, the clink of ice in the tumbler becomes a suspenseful underscoring in prelude to Jack’s sudden admittance of having once hit his son, perhaps in a drunken state, though he claims it was an accident when his son had mixed up pages of a novel he was writing.

In The Shining, whiskey is a minor but pivotal character. The haunted hotel is a significantly larger character influencing Jack’s innately eager aggression. But the whiskey is the doorman, ushering Jack across the threshold into madness.

Whiskey’s casting here reeks of old-school American temperance propaganda. Whiskey as the elixir of Lucifer. This befits the old hotel’s upscale Prohibition era vibe. It’s also true to the film’s own era, when whiskey was not popular and bourbon in particular was considered the vice of crotchety old men and drunks.

But rather than Christianity’s Satan, I prefer the analogy to Goethe’s Mephistopheles, the reluctant but dutiful chauffeur to the egomaniacal Faust on his journey of desire. Like Goethe’s accommodating devil, whiskey has no evil intentions. Whiskey is a natural, inanimate object. Passive and consistent. How we use and abuse it says more about us than it does about whiskey. The devil doesn’t make us do anything. We choose to shake his hand, pretending it’s not our own.

James Bond

James Bond famously orders his Vodka Martini shaken, not stirred. But when Daniel Craig took over the role with the 2006 remake of Casino Royale, a stark changing of the guard was signaled when Craig’s Bond is asked his preference by a bartender. “Do I look like I give a damn?” he growls impatiently.

Though the silver screen Bond is best known for his martini habit, Bond on the page was much more of a whiskey drinker—and not even scotch whisky so much as bourbon and rye, whether sipped neat or in a cocktail.

Though whisk(e)y makes many appearances across the James Bond film franchise, it plays less of a specific character in the Bond series as compared to those movies already mentioned. Here whiskey functions as more of an accessory, like monogrammed silver cufflinks or a Rolex watch. Whiskey is there to objectify high status, slick cool, an ease for indulgence, and a refined taste for danger. Alongside all the other drinks ornamenting the action, whiskey helps decorate the many luxurious international locales Bond frequents:

A Mint Julep on a wealthy horse rancher’s estate in Kentucky—Goldfinger (1964).

Scotch at an extravagant party in Scotland—Casino Royale (1967).

Bourbon and water in Harlem and a Sazerac in New Orleans—Live and Let Die (1973).

A glass of Jim Beam with American CIA agent, Felix Leiter, even though they’re off the coast of Morocco—The Living Daylights (1987).

Perhaps the most glaring product placement for Macallan Single Malt Scotch in film history, served variously at beach bars, a villain’s island hideout, a London apartment, you name it—Skyfall (2012)

Unidentified whisk(e)y shows up on innumerable train rides and in most apartments, hotel rooms, and offices. And whenever Bond meets with Judi Dench’s M in her office, it’s bourbon all the way.

Although whiskey is merely set dressing in the Bond films, its prevalence helps imprint in our memory the image of Bond with glass in hand. Usually a martini glass, granted. But that next train, apartment, hotel room, or office with its requisite stash of brooding amber liquid is always just a few scenes away.

Casablanca

Even more so than the Bond films, a great many spirits make an appearance in the 1942 classic, Casablanca. How many exactly? Well, late one pandemic era stay-at-home night, I counted every drink sipped on screen in the movie. Here’s the tally in 4 minutes 39 seconds:

An International cast of brandies, liqueurs, sparkling wines, and of course whiskeys, along with coupe after coupe of anonymous cocktails, comprise an ever-present crowd of background extras for the movie’s primary setting, Rick’s Cafe Americain. Feeling less like set dressing as with the Bond films, here the chorus of drinks work hand in hand with the actors to help depict the cultural crossroads that Morocco’s port city, Casablanca, became during World War Two.

Today we watch Casablanca as a period piece. It’s easy to forget that when it originally came out it was an up-to-the-minute contemporary drama, set in a war still actively underway and not yet defined by hindsight. The movie even incorporates actual wartime newsreel footage, fresh from the frontlines, adding to a genuine sense of immediacy that feels visceral still today. In 1942 the world didn’t yet know how the war would end. Fittingly, the cast of Casablanca didn’t know how their movie would end, even as they were filming it!

Much has been written about the making of Casablanca, how it was just another picture on the crowded studio conveyor belt with no particular aspirations to eternity. It’s striking how many accidents and improvisations contributed to the movie’s complexity and authentic sense of spontaneity. This alone draws a parallel alongside whiskey: No amount of planning can control the mysterious creative process that happens in the barrel.

As for whiskey’s particular role in Casablanca, bourbon first makes a formal appearance when bar owner Rick Blaine (Humphrey Bogart) is consoling his shock late at night after closing time. His former love, Ilse Lund (Ingrid Bergman), who left him abruptly and without explanation when they were escaping German-occupied Paris, has turned up in Rick’s bar on the arm of Victor Laszlo (Paul Henried), Czech leader of the French underground, who himself escaped a German concentration camp and is seeking safe passage to America. There are a lot of plot points to relay here in order to clarify exactly why all this would compel Rick to pour his way through half a bottle of bourbon. But also I wouldn’t want to spoil it for anyone who has somehow managed to not yet see this movie. (If that’s you get to it!)

Up until this scene, drinks have involved a lot of Cointreau and brandy. But now the American leading man is in turmoil, so, out comes the American bourbon. Ilsa arrives hoping to explain things, but Rick isn’t having it and keeps pouring the bourbon. Their conversation does not go well. In an awkward meeting with Ilsa the next afternoon, Rick blames the bourbon for his acerbic behavior toward her the night before. But Ilse won’t play that old blame game, and holds Rick responsible for the bitter man he seems to have become.

In subsequent scenes, elegant cocktails continue to parade through every shot. Bourbon makes a return when Rick visits his neighboring bar, The Blue Parrot, owned by the semi-legal Signor Ferrari (Sydney Greenstreet). Ferrari hopes to ply Rick for some hidden travel visas that half the cast want to secure for themselves. Ferrari opens a bottle of bourbon to appeal to his inscrutable American friend.

That’s the last explicit appearance by whiskey, though it most certainly makes many other appearances among the cocktails.

In short, bourbon is cast alongside the other actors in Casablanca, many of them actual refugees themselves, to populate the international nexus that is Rick’s Cafe Americain. Bourbon’s association with hardened American square-jaws like Bogart’s Rick Blaine is put to clear use here. By contrast, the local Chief of Police, an eloquent Frenchman named Louis Renault (James Mason), orders a great deal of champagne throughout the film. With nationalism vibrating like pent-up lightning in the seaside Moroccan air, each character’s choice of drink signals where their political allegiance lies. Alcohol as political proxy.

Finis

There are other films one could analyze for their casting of whiskey. It’s often just off camera when not in close up. Susan Cheever’s excellent book, Drinking In America: Our Secret History, tracks the many roles whiskey has played in American history, from old pal to revolutionary to glorified criminal to ambitious politician. It’s no wonder Hollywood movies in particular use whiskey to help tell our stories.

These movies would also make for great drinking games. Although I don’t recommend trying to match the cast of Casablanca drink for drink. You might end up stuck in Casablanca yourself!

Thank you, Mark. What a great piece for film buffs! Look forward to reading it again for more detail and revisiting some of those terrific films. My introduction to alcohol in the movies came mostly through Screwball Comedies, which could have been called “Highball Comedies!” All those lovely shipboard romances, the Lubitsch farces along with visions of suave Cary Grant, and arrogantly elegant William Powell knocking back their martinis. I couldn’t wait to turn 21 and have one, certain I would swoon with the first swallow. In reality, my response was closer to a spit-take followed by a sense of deep disappointment. That’s Hollywood for you!

LikeLike

Ha! I think “Highball Comedies” is my new favorite genre. 🥃

LikeLike