Whiskey fans sometimes refer to a flavor note they call “funk.” What is that?

This descriptor often gets applied to whiskeys from the early 2000s or before. Older Wild Turkey gets it a lot. Most anything from the 20th Century. Usually bourbons, more than scotch. But scotch as well. Contemporary whiskeys occasionally also receive the “funk” descriptor, so, it’s a term that would seem a bit loose.

A bottle of Bertie’s Bear Gulch Bourbon had quite a funk to it for me, and I did not like it at all. Think roadkill in the hot sun. I tried and tried, but never came around to it. So many people say they like funk, seek it out, and even pay dearly for it when it’s some older bottle that once sat on bottom shelves for $10 or less. So did Bertie’s have a funk, or was it just whiskey I really didn’t care for?

It was Wild Turkey’s Forgiven Batch 302 that drove home the funk for me, and helped me understand it. At first I did not like it. Smelled like spoiled raw chicken meat. But as the bottle aired out, that specific aspect dissipated and evolved into something more herbal, and I began to come around to it.

I also got a funk note on the Anderson Club 15, distilled in 1990 and bottled in 2005. This was herbal as well, like a damp mold. And then the 2022 Springbank 15 release also had a funk to it, something more sulfuric.

So I was curious what specific brands other people have tasted funk in, and how they describe what “funk” means in terms of flavor or aroma. I asked my friends on the social meds, and thoroughly enjoyed reading through their responses. Here is just some of what they shared, with things in bold that came up often:

Think ‘musty’.

Almost mildewy leather or damp wood. Old rum has it in spades.

Wet stone, cave puddles, the bleu crystals in certain cheeses, or amonia. I taste it in a lot of old Heaven Hill…

I describe the taste as being similar to the way an old book that hasn’t been touched in decades smells when you first open the cover. I‘m a big funk fan.

I typically try to add some form of adjective since there are so many ‘kinds’ of funk. I.e., damp wood funk, overripe fruit funk, earthy moss funk, dusty chair funk, etc.

I’ll be curious to hear if anyone has a specific and consistent description. I’ve interpreted it as an unexpected nose or taste that is off, but not off-putting. I like the funk. Can’t say it’s a consistent flavor profile for me though.

I got this ‘funk’ in Laphroaig when I started drinking scotch. Medicinal, dark smokey barrel taste. As for bourbons, that would be Old Elk Wheated Bourbon. It gives me an old taste, like a dusty old book or the smell of old barrels (port barrels?)

This is a great question. On the bourbon side… for things like dusty Wild Turkey, it’s something like an antique leather book or walking down into a musty basement. It gives you a mental image of something that is old and worn. It’s also present on the scotch side. Places like Campbeltown and distilleries like Craigellachie market themselves on their funk. For Craigellachie, it’s a sulphur component that makes it unique. For malts from Campbeltown, it is generally described as ‘earthy’ and this can mean different things to different people. For some it’s a mushroom like note, for others a wet burlap sack, some call it a mulch–like note (one of my favorite descriptors) and others still refer to it as ‘vegetal.’ In reality, it’s just a call back to what kinds of references you’re familiar with.

I think of funk in whiskies as something that could be an off note, but (maybe) isn’t. It’s literal funk, in the sense of something that seems to have spoiled and/or smells bad. (Rotten eggs are funky; orange blossom water isn’t.) Stereotypically, that could be the Ledaig ‘wet dog’ note or ‘machine oil’ in a Longrow or a ‘baby vomit’ Laddie or any number of other things. As [my friend] says, that’s often a signature note of a distillery—though for me, anyway, it doesn’t have to be.

Musty/dank, and in some cases, just this side of unpleasant. Like a damp basement that hasn’t started to mold… yet. For anyone who has ever been up in a silo full of corn silage in the summer, you will be reminded of that funk by Rare Breed… to the point of distraction.

Musty, earthy, farmland soil. Dusty dunnage warehouses. Damp firewood. Balcones has what I refer to as a rubber band funk. It’s like burnt tires, soil, grain.

There are many different flavors of funk out there… but one thing they have in common: you can’t fake the funk.

Damp musty wood. Like the smell of a log cabin after a rain on a hot day… but in a good way!

Walking from an antique bookstore into an old forest after it rained.

Grandma’s couch. That’s funk.

Intrigued by the many repetitions—lots of mustiness, old books, industrial variations, “off” notes, damp this and that—as well as the range of brands mentioned, I decided to line up an impromptu funk flight, drawing on what I had open on the shelf.

Here are some brief notes, all taken using a traditional Glencairn, and focusing in on the funk aspect:

Anderson Club Bourbon Aged 15 Years

Right away on the nose, behind an initial wall of toasted cinnamon lurks a musty funk, combining old dust that hasn’t moved for a long time with something like bacon fat that’s been sitting out long enough to cool, tempting spoilage without yet crossing over. Behind that then comes dark cherry, chocolate, and root beer.

Then on the taste, that funk leans forward further through the cinnamon wall, without taking over. Just enough to assert itself with more clarity. The cherry, chocolate, and root beer are right there to flank it. And a light oak note enters to color everything like a faint sepia wash. It is a model of balance.

The finish then lingers lightly, with an emphasis on the oak and the funk, with just a dash of cinnamon and a smudge of chocolate.

As with my first formal tasting of this, I am reminded of the better half of my experience with Wild Turkey’s Forgiven Batch 302. That bottle went from alarming to pleasant enough. This Anderson Club was fine out of the gate, good by the time I took formal notes, and now as it has continued to air out I find it really good. It’s that confident sense of balance.

This leaves me theorizing that this particular brand of meaty funk might have something to do with the 20th Century. The two distilleries—Wild Turkey and Heaven Hill—have different grains, mash bills, water sources, yeasts… Was it the particular quality of oak barrels back then? Pipe cleaning standards? Or…?

Craigellachie 12 Year Single Malt

At first on the nose all seems sweet, dark, and red-fruity, with rich caramel undercurrents. No immediate funk. But with time a sulfuric aroma drifts forward like a yellowish brown fog, revealing the sherry cask wherein this scotch spent its 12+ years aging. Eventually some subtle ash begins to drift through as well, nudging the sense of damp fog toward a drier, slightly acrid smoke.

On the taste and finish, the ash immediately comes on stronger, floating now on a dark river of sweet red fruit and caramel. Combined with the subtle sulfur, the ash conjures Dickens’ London, when the air there was by all reports aromatic but not too healthy. Luckily there’s nothing toxic at work here (aside from the alcohol, of course!) and these Dickensian industrial funk notes contribute a rough complexity to the sumptuous, sweet, smooth foundation of this Speyside scotch.

Hakata 18 Year Japanese Whisky

Hakata is made from a 100% barley mash bill, using the Japanese flavoring mold, koji, to jumpstart fermentation rather than the more traditional malting process. Koji is known for its distinct umami taste, a kind of earthy meatiness. The Fukano Whisky brand also uses it, though their whiskies are distilled from rice. Both brands begin as shochu, the common Japanese liqueur, which is distilled over a longer period than whisky tends to be. But Fukano and Hakata then get barreled and aged like whiskies.

This Hakata 18 Year’s particular variation of funk is not a mystery—it very clearly comes from the koji mold. But this particular release was aged entirely in sherry casks, which offer their own funk element. Double the funk? Let’s get into a glass.

On the nose: must, mold, a thick beef steak cooked rare and served cold, sulfur reminiscent of boiled egg. On the taste: the nose’s mold, sulfur, and egg, now supported by strong rich cherry and dark red plum, ending with a swing back toward that meaty koji mold. And then on the finish: a balanced trifecta of sulfur, sweet red plum, and the meaty koji mold.

Those sweet red fruit notes do quite a lot to balance the sulfur/koji funk aspect. But the funk is strong enough, and frankly weird enough, that this otherwise tasty and intriguing whisky teeters for me on a thin ridge between decadently delicious and nose scrunchingly off. It’s whatcha call a conundrum.

But it’s not boring!

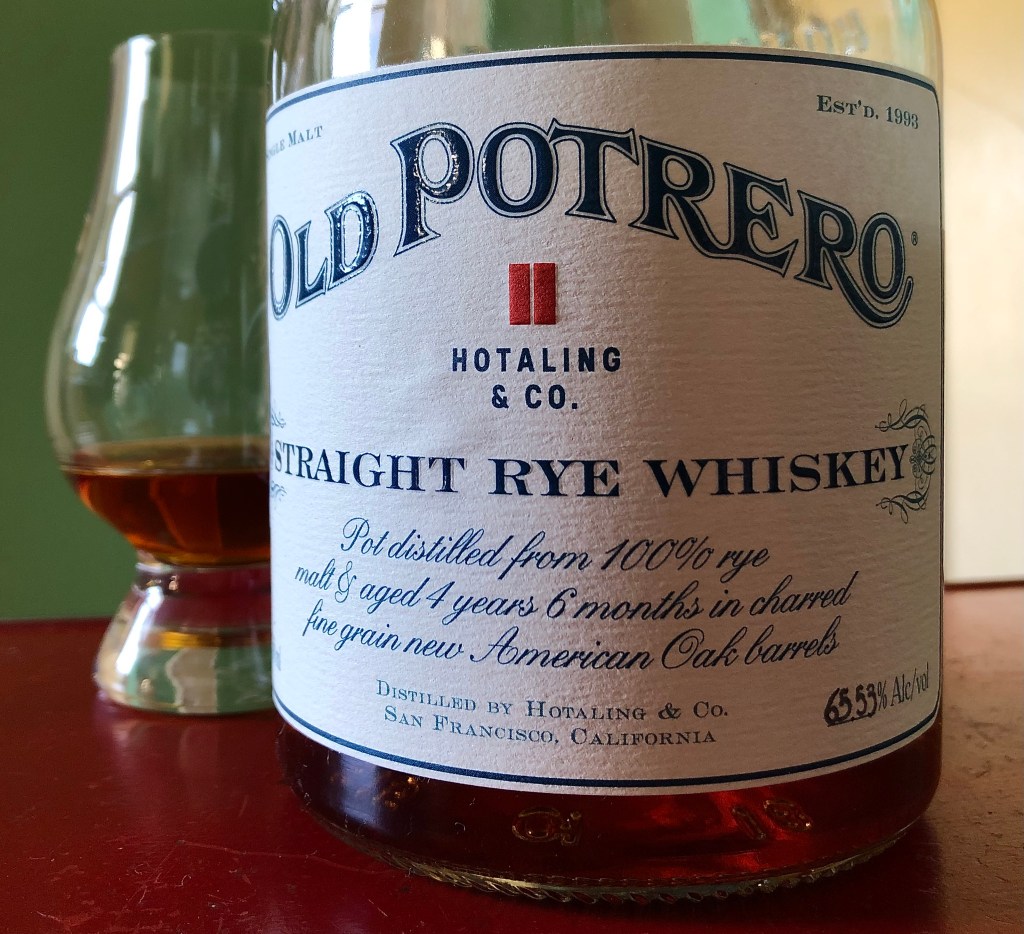

Old Potrero Cask Strength Malted Rye

This particular release is a single barrel selected in 2019 by PlumpJack Wine & Spirits in San Francisco, and bottled at its natural 131 proof.

On the nose, the funk arises from Old Potrero’s signature maltiness. The brand is among the rare 100% malted ryes, qualifying as a single malt whiskey, though it’s aged in new oak barrels rather than used casks as with scotch. Here the malt aromas combine with the dry rye spices to forge a kind of old fashioned American industrial quality, back when industrial work was done with bulky equipment made of solid iron and thick splintery wood beams.

On the taste I get the same strong malt notes, only brightened now by the surrounding rye spice, some sparkly cinnamon, and very faint cherry. The high-octane proof adds a fiery aspect that conjures the raw blazing flames of 19th Century railroad or other engines—again that bulky iron and wood combo, now all fired up!

Rieger’s Bottled in Bond Rye

On the nose I get a dry herbal rye grass and hay note, alongside a subtle but distinct creosote note.

Creosote is a carbon chemical made from the distillation of plant, wood, or coal tars. It’s often used as a wood preservative to protect things like railroad planks and electrical utility poles from termites or fungal rot. None of this sounds like anything anyone would want to ingest! But rye grain is a good source for creosote, and so this note does sometimes come up in rye whiskeys.

Moving on to the taste, the herbaceous bouquet continues, and the creosote shifts to something even closer to tar. However, it’s quite submerged amidst syrupy dark cherry and chocolate notes. On the finish it lingers only very faintly.

Creosote has never been a note I’ve liked, until this bottle of Rieger’s! I remain as surprised now as when I first tried it by how the creosote actually adds positively to the complexity of the whiskey, with its industrial funk—much in the same way peat can add to the uniqueness of a scotch.

Springbank 15 Year Single Malt

The night before this tasting, I shared this bottle with some friends. It had evolved since I’d last tried it. Less funk!

Tonight, on the nose I get a musty sulfur, dry sherry tannins, and also something very dry like dusty oak mulch in a hot and arid northern California summer. On the taste these notes persist, but are wetted by dark red plum and baked papaya. A diesel smoke note wafts into things, along with whiffs of peat and sulfur. Then on the finish all tilts quite dry again, with only lingering droplets of the sweeter fruit notes.

It’s very much as I remember it from my last formal tasting. Whereas then the various notes felt slightly ajar, now they seem to have settled in together, like a good homemade soup on its third day. The funk at work, in any case, is a dry potpourri of diesel, sulfur, peat, oaky wood smoke, and sherry tannin.

Wild Turkey 101 from 2001

I opened this bottle for this occasion. How could I not include some dusty Wild Turkey in a post on funk?

Having been vatted and bottled in 2001, the bourbons in this batch were likely distilled in the mid-1990s. The famous and widely hunted Wild Turkey funk was still in full force back in that last decade of the 20th Century, before the Wild Turkey entry proof had been raised from 107 to 115. Other factors are unknown of course. Was the way they cleaned the equipment back then different? Does this 2001 bottling contain any of the old cypress fermentation tanked distillate? We can’t know.

On the nose I get strong dusty oak up front, heavy on the dust. Then dried cherry and strawberry, a light caramel syrup, and baking spices. To my surprise, nothing I would immediately recognize as “funk.” Very interesting, considering the relative dependability of these older bottles to feature it.

After writing the above, I then leaned in for a sip and there it was: a gentle but distinct whiff of that meaty, fatty, Wild Turkey funk. I sipped it. Oak and baking spices up front, drying oak tannin, some caramel and chocolate, faint dried cherry if I search for it… No funk. 🤔

So I waited…

Going in for another sip, that gentle but distinct presence of funk remained among the aromas. On the taste now, the drier oak, spice, and dust aspects still dominate, with the various sweet notes still subdued by them. Without squeezing my senses too hard to search, I do now also get a bit of the funk. It’s subtle, but it’s there. Then on the finish it’s gone straight away, the dry elements still taking the lead.

To say this 2001 bottle of Wild Turkey 101 is a disappointment would be misleading. It’s an excellent, perfectly enjoyable vintage bottom-shelf bourbon. But given why I’m tasting it today, I will admit to being a bit disappointed that it’s not funkier. Ah well. What subtle funk there is does add a thread of complexity to the burlap roughness of this classic bourbon. It’s the kind of bourbon that makes you want to slam your glass down hard on the table when you’re done with it. Formidable, no nonsense, friendly, and uniquely itself.

Last Call

In lining up this seven-whiskey funk flight, the results paralleled the many responses I got from my friends on the social meds. Lots of notes repeating from whiskey to whiskey. An infinite spectrum of aromas and flavors within the commonalities. And interesting time travels, like to Dickensian London or a 19th Century railroad.

While no single definition of “funk” seems possible, or even necessary, one phrase that came up a few times in variation among my social media friends rings true for me as a through-line: “off, but not off-putting.” That could refer to the various food related notes—meaty, vegetal, cheese-like. It could refer to elemental notes, like dust or stone. And it’s perfectly apt for the environmental notes, like musty basement, old bookstore, or Grandma’s couch.

So, whatever the specifics from whiskey to whiskey, it would seem there is something off and old about funk that grabs attention, intrigues, often perplexes, and in the best cases, to our surprise, pleases.

Cheers to the funk!