What’s a dive bar? That’s a question that’s been asked, answered, and the answers debated, for generations.

My partner and I were walking along San Francisco’s 24th Street one recent afternoon and we passed by Pop’s, established in 1937 and looking like it. We didn’t stop for a drink. But glancing in at the cluttered decor and varied clientele, the perennial question arose. Was it a dive bar, and what is that exactly? We debated.

The previous night, we’d gone for drinks at Evil Eye and then Doc’s Clock, both on Mission Street and walking distance from Pop’s. Were they dive bars?

Evil Eye, definitely not. The $16 cocktail I ordered there featured “sage-washed scotch.” The bartender was a young man, neatly bearded, efficient, and amiably attentive. The decor—even the bathroom graffiti—seems to have been curated and installed to look vaguely 1970s, rather than accumulated naturally over time.

Doc’s Clock? Likely a dive. My partner ordered a $3 canned beer and I had a $9 Old-Fashioned. The bartender was a middle-aged woman, hair disheveled, efficient, and amiably inattentive. There has been an evident accumulation of knickknacks and eclectic furniture since the bar opened in 1951. But Doc’s Clock shows up on a few “best of” lists—always a threat to any bar’s diveness. Also, there is contemporary art for sale on the walls. So how on or off the mainstream map is Doc’s Clock? A “best of” write-up is not a bar’s fault, of course. And why would local art for sale be a factor for me? I’m not sure. Was it a question of intent? Was the featured artist a regular? Not a regular but someone who approached the bar? Was it the style of art? Do these details really matter? What does matter?*

*Later I came across an answer to the art question. In 2024 Doc’s Clock was among nine Mission District bars participating in a dive bar art crawl, organized to counteract a lingering post-pandemic drop in customer traffic. Very cool idea!

As bar journalist Stuart Schuffman somewhat recently put it:

Just like explaining the meaning of “cool,” it’s impossible to unequivocally define what a dive bar is. You just kind of know one when you see it.

I find this question of what exactly is and isn’t a dive bar to be a very American question, for at its heart is the question of authenticity.

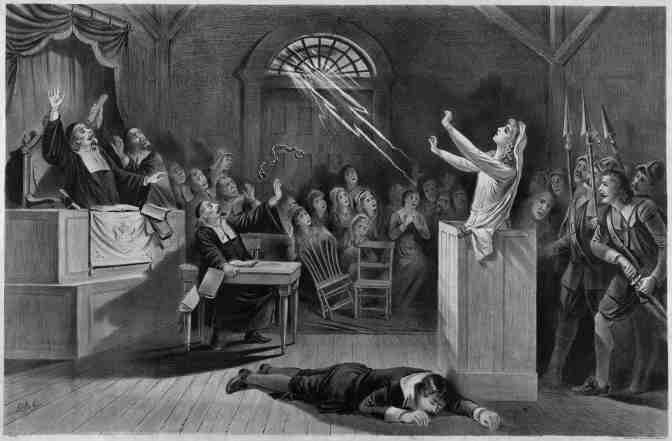

Americans have been obsessed with authenticity since colonial Puritans made their lasting imprints on our then embryonic national character, with their utterly hypocritical relationship to authenticity. For the Puritans, one’s show of devotion to God mattered above all else, and particularly that this show be believed by the larger community. The outward performance of faith is what ultimately counted, not the inner truth of that faith. And if one’s performance was not believed, accusations and hangings often followed. Performativity and violence have been core to the pursuit and enforcement of American “authenticity” from the start.

The relationship between this conflicted puritanical impulse and our contemporary conception of dive bars offers nuance to the question of American authenticity. Back in the Puritan days, if you faked your confession well you could get away with it. But there’s no faking a dive bar. Despite the term’s endless debates, dive bar status is certainly a result not of careful design but of time and economics. Time takes the time that it does. And economics takes us to issues of class and race. And for those, one need only consider the origin of “dive bar” as a term:

The first known use of the term “dive” in relation to a bar is Dug’s Dive in Buffalo, New York, established there sometime in the 1830s by a former Black slave, William Douglas. Tucked well out of plain sight, in the perpetually damp basement of a waterfront building housing several other Black-owned businesses, Dug’s Dive offered saloon, boarding, and brothel services to the transient population of its neglected corner of the bustling canal-port city. It is very likely that Dug’s Dive was also a stop on the Underground Railroad network, providing respite to escaped slaves making their way to nearby Canada.

Like so many things in American culture—music, fashion, colloquial slang—so too is the “dive bar” concept derived from Black culture. A bar hidden beneath the surface of a city (hence the dive) offering cheap sustenance and respite to people for whom “down on their luck” was an understatement. Dug’s Dive was among the original Third Places, a safe space for Black people to momentarily escape the street-level brutality of early nineteenth century American life.

In a fiercely loving article on dive bars, bartender Jabriel Donohue makes a few key points. Rather than paraphrase Donohue’s eloquence, here in full I’ve quoted four salient insights that helped guide my own San Francisco dive bar journey:

What marketers, trendsetters, and even many bar owners fail to grasp is that a “dive bar” is more than an aesthetic. It’s not something that can be papered on the walls or adopted by fiat...

Dive bars are deeply loved institutions, regularly full of passionate patrons who have a sense of individual ownership of the place. Like most tribal environments dive bars can be moderately unsafe to outsiders, with their own customs that normal bars might not abide…

It’s unfair to pigeonhole dive bars as purveyors of inferiority. In truth, some dives offer delicious meals at prices so low it’s hard to comprehend. They’re irreplaceable domains of local culture where income, social status, fame, and everything else don’t matter. They’re great equalizers…

Popular non-dive bars have a different culture. They’re where you go to be seen, to experience a new trend, or to impress a client or a date. Sometimes they’re just where you go to have a great time and watch the game. Not being a dive bar does not make a place lesser. But dive bars have history and community. They’re where a person can turn when they have nothing and need a place to be. They’re bars where your mother can point to the corner stool where your grandfather always sat. They’re the keepers of the “remember when.”

My first San Francisco bar hop here on the blog was a zigzagging bounce around the city, in an effort to identify what makes a “good San Francisco” bar. That hop included historical neighborhood bars like Club Waziema, lowkey pubs like Durty Nelly’s, and high-end cocktail lounges like Cold Drinks Bar. This second hop is focused on dives.

Of course, whether each bar visited here is a dive will remain debatable. But that’s what another round is for.

There’s also the problem of “best of” lists. To curate this post, were I to consult any such lists, I’d be stepping into one of Donohue’s points, that “the moment a place is written up as a ‘great dive bar,’ its dive bar credentials suffer.” So I committed to finding my destinations entirely on foot. I may have inadvertently wandered into some listed joints anyway. But at least I didn’t know it. Ignorance is bliss!

Further regarding lists, do I myself risk subjecting the bars I write about here to “best of ” contamination? Likely not. First, this isn’t a “best of” list. These are simply a handful of places I stumbled into. Also, my readership just isn’t that widespread! (Does that make this a dive blog? 😉🥃)

So pour yourself a shot of Evan Williams, or crack open a Miller High Life, or stir up an Old-Fashioned with whatever’s handy. And enjoy the hop!

Pop’s Mission District

540 Inner Richmond

The Ha-Ra Club Tenderloin

Mr. Bing’s Cocktail Lounge North Beach / Chinatown

Molotov’s Lower Haight

Last Call reflections on the hop

🥃 ☜ clink these to jump back up here

Pop’s

Pop’s is the bar that got this whole inquiry going, so I figured it made a good place to start. I didn’t know it was on any lists at the time. Since then I’ve read Stuart Schuffman’s excellent 2023 feature article on Pop’s, in which this interesting comment from owner Tom Tierney appears:

I know it’s splitting hairs, but if you call Pop’s a dive bar, it’s kind of an insult to dive bars… Because dive bars have their own place in San Francisco and in America. I consider ourselves a neighborhood bar.

Tierney implies a distinction between “dive” bars and “neighborhood” bars. His comment also expresses a certain respect for dive bars, which Tierney does not appear to want to tarnish by counting his “neighborhood” bar among their rank. But are these two genres of bar mutually exclusive?

It seems to me a “neighborhood” bar, which I take to mean one frequented in significant number by its residential and working neighbors, can also happen to be a “dive” bar. But isn’t a “dive” bar inherently also a “neighborhood” bar, since one key aspect of dive bars is their regular and dedicated clientele, which one can reasonably assume will be from the neighborhood, not trekking in from across town or having consulted a tourist guidebook?

Discuss.

I went to Pop’s at 7:30 AM on a Friday. Why? Because one can! Not many bars in San Francisco are open from 7:00 AM to 2:00 AM. Maybe a handful. Pop’s is one of them.

Established in 1937, Pop’s has had many owners and two locations on its 24th Street block. Whether catering to baseball fans in the 1960s when there was a stadium nearby at 16th & Potrero (now a Safeway); the local Latinx community when the bar was owned by Frances Prieto in the late 1990s; a mixed “alternative” crowd in the early 2000s; or its current range of working class clientele, including night-shift nurses from nearby SF General Hospital; what appears to have remained consistent over the generations is a no-nonsense, easygoing atmosphere wrapped in walls adorned with history.

I was one of three customers when I arrived, soon joined by three more. The top morning orders seemed to be a beer and a shot, or a shot on ice with a pint of water. I was the sole Irish Coffee. The bartender had to run across the street to buy a fresh can of whipped cream. “You want me to run and get that for you?” offered a regular. The bartender declined and ducked out the back door. Within a few minutes he was back, gave the new can of whipped cream a good shake, and topped off my Irish Coffee.

Four of the five regulars knew each other. Their roaming chat was threaded with a good number of references to previous conversations long underway, peppered with fond jabs at other absent regulars.

A burly delivery guy popped in the front door, holding out a large box in one hand. “Hey! Did you order this fuckin’ thing? Says it’s for you.” The bartender leaned over the counter to peer into the large box, which contained a single 375ml bottle of some really expensive tequila. A debate ensued.

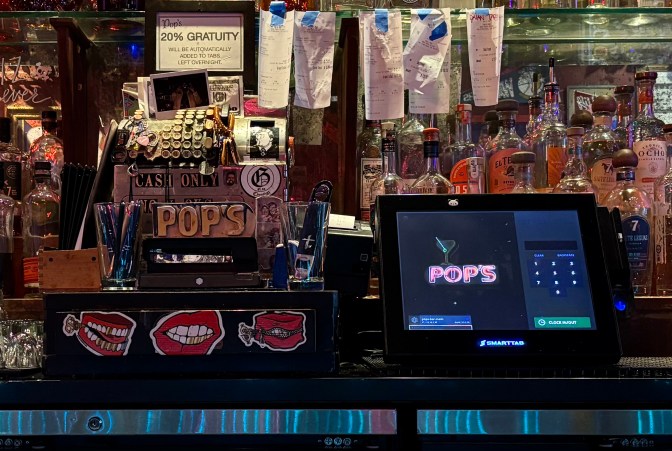

A weary but attentive old dog kept track of all comings and goings.

I sat at the bar for about an hour, sipping my Irish Coffee, reading a bit of a book, jotting some notes and shyly snapping a few photos. I felt quite out of place—a blogger among regulars. Bloggers may be one nudge away from their photocopied zine predecessors, and even less respected. But at a place like Pop’s anything digital feels quite anachronistic. Even the modern computerized register looks like an intruder, stationed next to the ancient analogue machine still holding forth at the center of the bar.

As if to highlight my sense of un-belonging, when I asked to settle up, my credit card was declined. “I tried it three times,” the bartender said. “Better call your bank.” Another card went through. Wrapping that up, I overheard a regular to my left asking the bartender about the word “zhuzh.” I thought she was looking for a synonym. I suggested “spruce.” They both looked at me. A beat of silence before the bartender clarified, “We’re trying to figure out how to spell ‘zhuzh.'” They went back to it, debating whether a “g” might be involved. I looked it up on my iPhone, and spelled it out for them. Staring and silence again, the bartender half-smiling with kind patience. I spelled it out a second time. The woman’s eyes glanced me over, her only movement. “Did you just look it up on that thing?” she asked. Yes I had. “That’s cheating. Use your brain.” Feeling like a dork, I smiled anyway. “That’s fair,” I admitted, to which the regular capped, “Don’t lie to people next time.” I didn’t know what she meant by that, since I hadn’t lied. I took it to be a general view on technology as purveyor of lies, and accepted the admonishment as part of my reprimand for having violated a regular’s routine with the bartender.

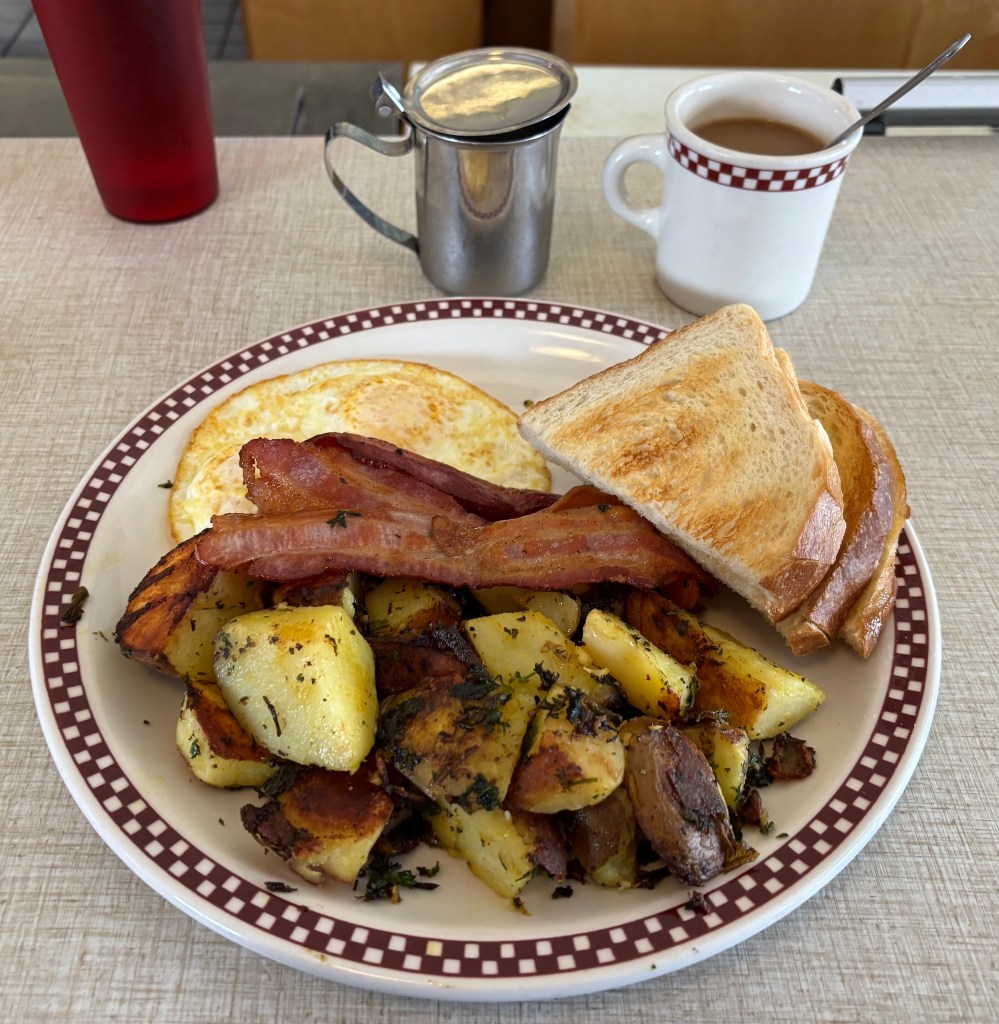

Breakfast was in order. I hopped across the street to St. Francis, established in 1918. St. Francis is the diner equivalent of Pop’s. Old-school, unchanged, still at it.

After my bacon and eggs and another round of coffee (minus the Powers Gold Label) I stepped outside to snap the above pic. My photo-op was held up by two thirty-something hipster bros, decked in the requisite beards and faux-poor fashion. One of them was involved in the very intricate process of applying an ornate locking apparatus to his expensive looking electric bike. The other was holding an iPhone nearby so the first could speak to what sounded to be his kid, who was apparently in Europe or some other timezone ten hours ahead of San Francisco. Once the parent-child call ended, with the bike now secured, the two men continued to discuss with admiration the fancy bike and fancier lock, each of which had specific brand names and insider jargon.

As my wait dragged on, I grew increasingly annoyed with these living breathing San Francisco tech bro clichés, embodiments of everything that’s ruining this city. Until I remembered, oh right, I’m standing here waiting to take a photo with an iPhone for a blog post about a dive bar and a retro diner in a neighborhood I don’t live in. So who’s the cliché? And the fool. 🙄

Authenticity always outs pretense. That Pop’s regular doing her morning crossword puzzle knows it. And my irritable waiting for my photo-op underlines it. As Donohue observed, dives are indeed great equalizers.

540 Rogues / aka 540 Club

aka Max’s 540 / aka…

540 Rogues makes an interesting case study for the dive bar debate.

I was drawn to it by the vintage-looking sign, tacked like an anachronism onto what seemed to be the facade an even older bank. Sure enough, the building at 540 Clement Street was originally built in the early twentieth century as the Bank of Italy. After the 1929 crash, Great Depression, and end of Prohibition, the building was repurposed as a bar. It’s been operating as such under a variety of owners ever since. That means customers have been bellying up to its bar counter for going on ninety years!

It only became 540 Rogues in 2021, when new owners took over the previously named 540 Club, itself among the many casualties of the pandemic-era shutdown. By all reports, 540 Club was a verifiable dive. One Yelper said the smell was so bad even the rats stayed away. Another reported a bartender not batting an eye after being informed the Baily’s they’d served had gone rancid—and they still charged the customer for the pour! Now that’s a dive.

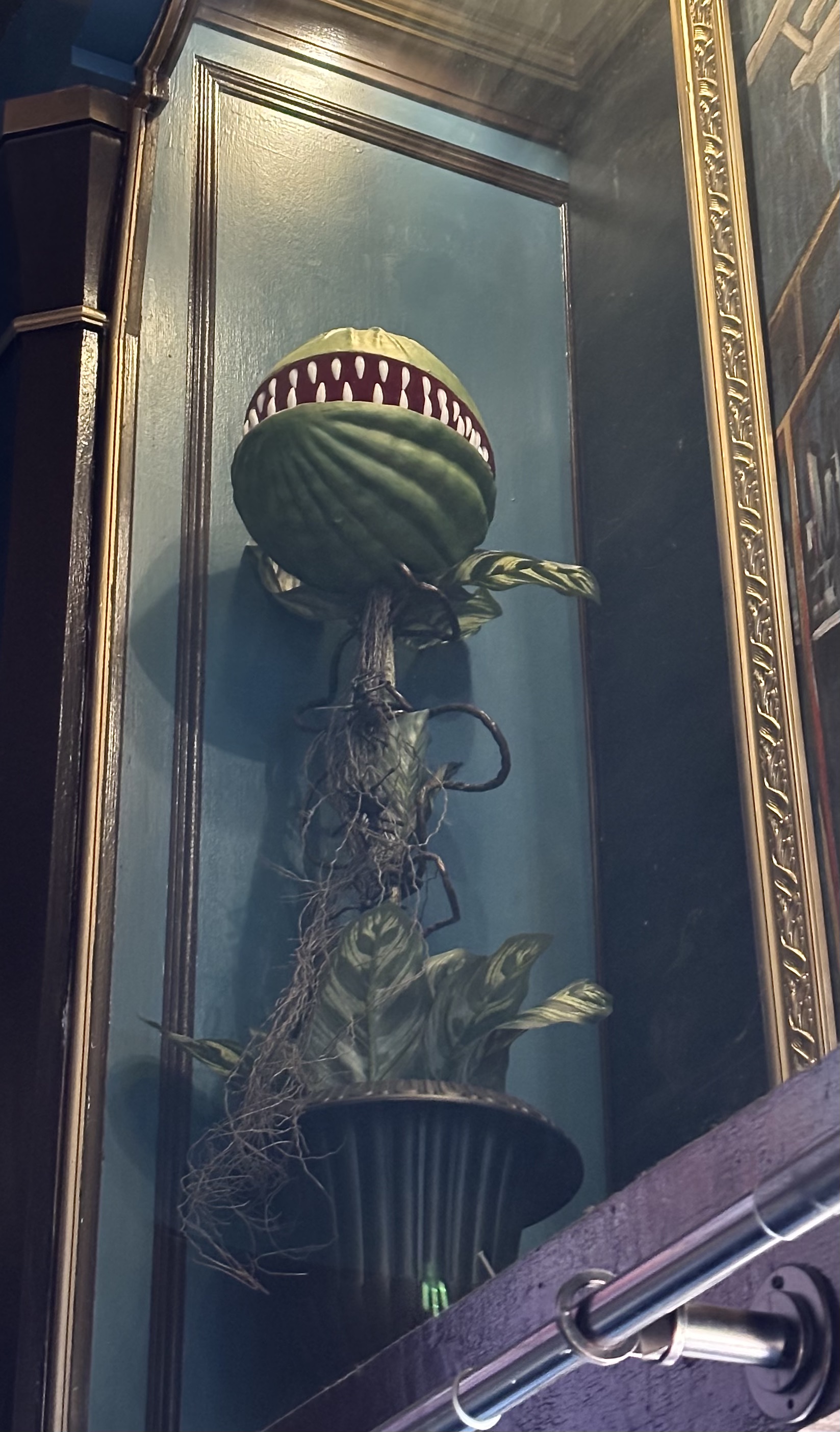

The 540 Club owners hadn’t taken down their predecessor’s outdoor signage, and the 540 Rogues crew hasn’t either. The bar’s current iteration shows a healthy appreciation for the generations that preceded it. The rodent-repelling smell is gone. But along with the old Max’s 540 sign out front and another variation on the wall inside, original details and knickknacks accumulated over time have been retained. The hull of the old bank and what looks to be some original ceiling structure. The old wooden bar. Vintage pinball machines. Most incongruously, an Audrey II perched up on a ledge. (If yuh know yuh know.)

There are subtle but discernible contemporary elements as well. New lighting fixtures. A fresh art deco paint job on the walls. Customer drawings neatly clipped to strings. A wide selection of contemporary craft beers on tap. Multiple large screen TVs running a range of sports and sitcom reruns.

These new aesthetic touches make a conscious bridge from past to present. The stretch of Clement Street from Arguello to roughly Twelfth Avenue was for many decades a working class Chinese neighborhood, along with Germans who’d left the Mission and Castro Districts where they’d originally landed. By the 1990s, young white college students had discovered the area’s affordable rent, and unwittingly set the inevitable gentrification in motion. Though many old-school establishments remain, with a strong Chinese community still the neighborhood’s backbone, nevertheless the lines out the doors at the Dim Sum shops are now largely white locals and tourists. The sidewalks teem with young upper-middle-class parents maneuvering their strollers and cute shoulder bags around grizzled middle-aged Chinese grocery clerks pushing their dollies and produce pallets. Nouveau diner cuisine rubs elbows with since-1968 Hamburger Haven. The old Asian American Theater is now a fitness gym.

I arrived at 540 Rogues around 12:15 PM on a sunday, shortly after opening. A silent, virtually motionless woman with short-cropped white hair was already seated at the end of the bar with a full pint of beer.

I ordered a Gold Rush—Jack Daniel’s, honey syrup, lemon juice. The inclusion of Jack Daniel’s nods to 540’s dive days. But the large ice cube is pure contemporary cocktail lounge. And the Gold Rush is indeed a cocktail created in the early 2000s, the dawn of modern mixology, at the famous New York mixology holy temple, Milk & Honey.

Around 12:45, half a dozen regulars arrived like a flock of birds. They settled in immediately, very comfortable in the place and the bartender happy to see them. With their voices filling the air, now the bar was coming alive.

540 Rogues is definitely not a dive bar. But, per Pop’s owner Tom Tierney’s distinction, it is certainly a neighborhood bar. And it’s a good bar. Clean. Lots of room to stand and sit. A wide variety of beers on tap. My $14 Gold Rush was tasty and well-made. And clearly the regulars remain regular—always a good sign.

To my personal tastes, the aesthetics do come across as somewhat compromised between the past and present. The relics adorning the fresh paint seem like nostalgic imports, not fully and organically integrated. But the intention feels genuine. In another five or ten years, with a few layers of dust and grime to meld the eras, the current variation on this ninety-year drinking destination will likely have fully settled into itself and achieved its own cohesive whole.

The Ha-Ra Club

Look at that facade! How could I not duck inside this place?

Located at 875 Geary Boulevard, near Larkin Street, The Ha-Ra Club stands smack in the middle of the Tenderloin, easily San Francisco’s diviest (diciest?) neighborhood. There are many dives to visit there. But Ha-Ra’s striking exterior is likely among the most eye catching. Before one even goes inside, the very sight of the place already compels the imagination.

Ha-Ra opened in 1956, in a space that had been a bar called the Sarong Club since 1943. The building itself was designed and built in 1922. By day it looks like it could be the facade of some discontinued 1950s Disneyland ride. At night the Twizzler-red neon casts light that almost feels sticky, making the red brick wall all the more red, conjuring kitschy sleaze like something out of a David Lynch film.

The mid-century tackiness makes a compellingly abrupt clash with the towering Spanish Colonial Revival architecture of the wall above, extending beyond Ha-Ra left and right.

Oddly, the 800 block of Geary seems to have been intentionally populated with buildings of ornate grandeur incongruous to the longstanding downcast of the neighborhood. In addition to Ha-Ra’s 1922 Spanish Colonial facade, there’s the toweringly palatial 1927 Castle Apartments, which takes Ha-Ra’s Spanish Colonial inclinations to significant heights; and the pseudo Byzantine 1914 Alhambra Apartments, with its busily intricate detailing.

In my post-college years, I often went to Edinburgh Castle Pub, just a block away from Ha-Ra, where you could get a pint with fish & chips for pretty cheap. (The fish & chips was actually made by a Chinese outfit down the back alley behind Edinburgh Castle. It came wrapped in newspaper, and back then newspaper ink was—well, you didn’t want to ingest it. I ate a lot of that fish & chips & ink in those days. But I’m still livin’!) I typically ended up at Edinburgh Castle after performing or house managing in the annual San Francisco Fringe Festival, which operated out of a handful of Tenderloin area theater spaces. So I was always going there at night. How I missed Ha-Ra’s gaudy red glow in the murky Tenderloin dark I have no idea. Or maybe I didn’t miss it. Maybe I was afraid!

I was indeed afraid of Moulin Cafe, a divey diner just next door to Ha-Ra. I went there once when I’d first moved to San Francisco and was looking for an apartment. I had just looked at a unit at the Alhambra across the street. I loved the Alhambra’s architectural strangeness, out of place and yet very San Francisco in its excess. But as a newbie to the city, the Tenderloin scared me. When a cockroach sauntered across my table at Moulin Cafe like it owned the place, I decided I’d check out other neighborhoods. Moulin Cafe has since shuttered. But Ha-Ra lives on.

That name, Ha-Ra, comes from the combined first names of the original owners—Hank Hanestad, a wrestler, and Ralph Figari, a boxer. But it sounds like some kind of rousing cheer. Ha-Ra! The brevity and energy of it match the bold design of the place.

Inside, the red motif continues on brick and velvet walls and vinyl seating cushions. There are several unfortunate large 4K TV screens above the bar. But otherwise the history of the place has been carefully preserved, even improved upon, by the current owners, who in 2015 took over the bar from Ralph Figari’s son, Rick. The bartender told me Rick had let the place deteriorate during his tenure. The current owners found an array of wonderful features that had been papered or walled over. A backroom that once housed an illegal poker den was opened up to enlarge the main space. The beautiful tin ceiling was raised several feet to alleviate claustrophobia. Original photographs, a phone booth, salacious paintings hinting at the rumored brothel services, and other surviving knickknacks adorn the walls.

The prices are appropriately cheap—$5 for a canned beer and $8 for draft. I ordered a Ginger Ale with a shot of Jameson for $8. It tasted watery, as I’d expect an $8 cocktail would. But that’s not a complaint. You don’t go to Ha-Ra for mixology. It’s been lovingly cleaned up. But it proudly remains a dive.

I’d arrived shortly after 3:00 PM. A burly fellow was just finishing up hosing out half a dozen trash cans that had been emptied of their bottles and cans, and was now enjoying a pint at the end of the bar. An older man with a long scraggly beard was nursing an ice-filled glass of something strawberry-red, and stepping out for numerous cigarette breaks. His name was Rick, and he told me he’d been coming to Ha-Ra for forty years. (The former owner, Rick Figari, now a regular…? 🤔) He spoke highly of the original owners. “They were nice guys,” he said,”if they liked you. If they didn’t, look out.” Rick had lost his fair share of paychecks in the poker den over the years.

I love Ha-Ra. The bartender was friendly, sharing the history of the place with genuine enthusiasm for it. The drinks are cheap, featuring all the dive bar basics you need along with a spattering of contemporary beers and whiskeys. The pool table is well lit. There are plenty of cozy nooks wrapped in red velvet to tuck into. A wall-sized enlargement of one old photograph does come across a bit like a museum installation. But otherwise the care taken to preserve this mid-century dive is fairly transporting—back to the Rat Pack era of hard-drinking tough guys and broads, who laughed heartily and didn’t take guff from nobody.

Mr. Bing’s Cocktail Lounge

Mr. Bing’s holds down the corner at 201 Columbus Avenue and Pacific Street, at the border of Chinatown, North Beach, and the Financial District.

I debated whether to include Mr. Bing’s here. In addition to avoiding “best of” lists, I’d also wanted to steer clear of San Francisco’s main tourist drags. Columbus Avenue rolls out along the center of the ex-Beatnik Italian neighborhood of North Beach like a welcome matt. Tourists abound. But they tend to get their drinks at Tosca just across the street, or Vesuvio further up Columbus across Jack Keruoac Alley from the legendary City Lights Books. Though Mr. Bing’s does appear on lists, and was even ordained by Anthony Bourdain, tourists don’t seem to gravitate to it so much. In fact, while I was there, a quartet of clean-cut young bros entered, looking very in town for the weekend, took a few glances around and promptly left. Those of us parked there all had worn out clothes on, tattoos, appeared middle-aged and up, in no hurry, and with no crisp new bags from City Lights Books or Molinari Delicatessen—two excellent establishments, but very dog-eared in the tourist guidebooks.

201 Columbus Avenue originally housed a prohibition-era speakeasy named Zaza’s, fronted by an Italian furniture store. What became of Zaza’s and its furniture cover after 1933 is unclear. But in 1967, the lease was taken up by Henry Grant, nicknamed “Mr. Bing.” Grant ran the bar until his retirement in 2016, when he sold it to Jackie and Peter Cooper, Irish immigrants who were already running Ireland’s 32, a pub out on Geary Boulevard in the Inner Richmond District.

Although the new owners did a lot of remodeling, you might not think it. Mr. Bing’s still looks very lived in. It’s casual, dark, and grungy. The inevitable big screen TVs are mounted mercifully high up, where they don’t demand attention. (Interestingly, one screen had baseball on while another was playing 1970s reruns of Hollywood Squares. Gold star for contrast!) Every surface appears permanently stained or scuffed. The walls are decorated with assorted baseball and golf equipment, vintage adverts for local sports matches, and none too subtle Irish separatist propaganda. I did have a feeling one could get in a fist fight at Mr. Bing’s. Careful what you say about Ireland!

My Manhattan was fine, made with Bulleit Rye and whatever standard vermouth they use. For $12 it did the trick nicely, and was quite generously proportioned. They’ve got an expansive wall of booze, so, it seems they could shake or stir up any classic cocktail you might want. (Don’t expect duck fat washed bourbon or fresh thyme sprigs for garnish, though. Stick to the classics.) And the range of bottled and tap beers seems ample.

I sat near the window where I could watch the tourists heading up into the heart of North Beach, while also eavesdropping on a set of very clearly regulars parked at the bar. One curious fellow, whom I’d clocked sitting out front scribbling in a black notebook, eventually came in looking either tipsy or eccentric and ordered up “another Lemon Drop if you could.” He sat at the bar waiting for it. He was very thin with close-buzzed hair. His unique jacket would be the envy of any thrift store hunting TicToker.

But social media influencers aren’t likely to stumble into Mr. Bing’s, like the more analogue Anthony Bourdain once did. Mr. Bing’s isn’t fire or drip. It’s just cool. A good dive to help bring yourself back to reality—and maybe also drown reality out with a few too many. Just don’t side against Ireland!

Molotov’s

Molotov’s has been diving it at 582 Haight Street since 1999. Before then the space had been two other bars—The Midtown and Tropical Haight. The current owners took over in 2009 and have kept Molotov’s what it was always intended to be, a grungy down and dirty dive bar.

The Lower Haight neighborhood is far less travelled than its more widely advertised counterpart, Upper Haight, which capitalizes on San Francisco’s 1960s hippie-era history. There used to be a set of ill-kept public housing projects in Lower Haight, a city feature that always keeps tourists and middle class+ locals away. Lower Haight Street was—at a few addresses still is—a low-cost business strip where students, artists, and the working class could afford to shop, eat, and drink. In my college and post-college days I lived in nearby Hayes Valley—back then nicknamed Death Valley, with its own set of rundown public housing—and I’d sometimes walk up to Lower Haight to splurge on bacon and eggs at Kate’s Kitchen, or to sit for hours with a coffee at Café International where the extra-large tables accommodated the spread of books and notecards and other analogue forms of getting work done.

But those neglected Hayes Valley and Lower Haight public housing projects were eventually renovated. Hayes Valley has since evolved into one of San Francisco’s poshest neighborhoods. Lower Haight has been slower to turn that corner. Yet over the years it has definitely morphed into a fashionably pseudo-edgy strip, where contemporary award-winning mixology bars like Stoa now share the air with pre-digital stalwarts like Noc Noc, Toronado, and Molotov’s.

I could as readily have gone to Noc Noc, established in 1986 and the first bar to open in Lower Haight. Toronado soon followed in 1987. Both bars are very specific in their personalities and have managed to maintain their original integrity over the years. But I chose Molotov’s because, back when I was younger and more into cafes than bars, it was the Lower Haight bar that intimidated me most!

Why? The name suggests something anarchic and explosive, of course. But that’s just the name. It was the clientele I saw coming and going, decked in their tattoos and black punk and metal band T-shirts. They reminded me very much of the crowd at a bar in my hometown, Placerville, called Liars’ Bench. The parking spaces in front of Liars’ Bench were always clogged with motorcycles. The voices booming from within were rough and raucous, revving with confidence that gave no f*cks. I was not of age when I lived in Placerville, so I never went inside. But let’s just say when I saw the movie Blue Velvet, it seemed to me Frank Booth and his gang would have felt right at home at Liars’ Bench!

I’ve since gone to Liars’ Bench and it’s a good small-town dive. The drinks are no frills and cheap. The bartender and locals I met there were no nonsense and friendly. Just don’t dump on Trump or defend vaccines and you’ll be fine!

I popped in to Molotov’s early on a Friday. Two regulars were at the bar, very settled in, chatting intermittently with each other and the bartender.

I took a stool midway down the bar and the bartender moseyed over. I ordered the $8 beer and a shot—Hamm’s and Jim Beam White Label.

I mentioned that it had been a while since I’d hung out in the neighborhood, that I used to live in Hayes Valley when it was called Death Valley, and my roommates and I would come to Lower Haight for affordable fun. He smiled and nodded, poured himself a shot of something clear and held the glass up to me. “Welcome home.” We tapped our glasses on the counter and drank—him tossing his back and me taking a sip.

More regulars began to arrive, everyone sitting at the bar—except an elderly man with a severely hunched back, who sat in the corner by the front window and slept. Just as I’d remembered from the early 2000s, everyone was still wearing black T-shirts, jeans, chains, beards, dark eyeliner.

There’s a 2014 news report on a hilarious incident in which a woman wearing Google Glass[es] was using the new device—released to the public that year—to videotape people in the bar. The regulars didn’t like that, and she ended up outside in a fight and her purse stolen. Needless to say I was rather shy about snapping photos of the place with my iPhone. But it is quite a specific place:

Dark, red, black, too many stickers on the walls to count. A very Gen-X vibe to it all, with a healthy balance of humor and side-eye, like a punk zine run off at Kinko’s and come to life. And a pay phone!

Not to mention the bathroom…

Molotov’s was an interesting experience for me. I felt both out of place and right at home. The regulars aren’t the crowd I hung out with in high school or college. But that Gen-X vibe was registering in my bones like an electrical hum. And the bartender’s welcome had been as neatly welcoming as it gets—a straight to the point, no frills ritual.

Now that Gen-X has hit the other side of the hill, the social cliques of our youth (see The Breakfast Club for one breakdown) don’t mean nearly as much as the years under our belts. We’re a difficult generation for our bookends, the Boomers and Millennials, to comprehend. And the cliché is correct: We don’t really care if they get us. We’d still like to be able to get jobs. But we also understand everyone’s gonna die and you can’t take it with you—even if you back it up on iCloud—so, the playing field is even in the end.

Molotov’s is a dive, no question. And staunchly so. I suspect I’ll be there more often in the coming months and years, making up for lost time.

Last Call

On my previous San Francisco bar hop, asking myself what makes a “good San Francisco” bar, I concluded that any good bar, anywhere, must be authentic to its intentions. Doesn’t matter if it intends to be a dive or a high-end mixology lounge. If a bar is authentic in its choices around design, drink, and service—which together comprise atmosphere—it’s a good bar.

What makes a bar “San Francisco,” in my estimation, has to do with a confluence of Times—plural—in that a true San Francisco bar somehow taps authentically into more than one era at once. San Francisco has always been a city of transients, coming and going for one Gold Rush or another—be it actual gold in the 1850s, political expression in the 1960s, the freedom to be openly gay in the 1970s, or the dual tech rushes of the late 1990s and early 2010s. Many people have arrived, rushed, then left, or died trying. The graveyards may have all been removed to neighboring Colma. But the spirits of past entrepreneurs, optimists, opportunists, and eccentrics continue to linger in the city’s streets and third places.

And so, what’s a dive bar? Well, maybe as close as we can get to certainty on that question is that it’s (1) cheap, (2) in a grungy state of some variable measure, (3) serves what’s always worked, not bothering itself with modern mixology, and (4) it’s entirely authentic—no pretense, no bullshit, no exceptions.

I’d estimate it’s the first and last bits that are ultimately the keys, and the draw, when it comes to dive bars. Can I afford a drink there? Am I going to have to put up with any pretentious nonsense? Beyond that it’s whether you feel comfortable in whatever regular crowd the place gathers. I definitely felt like an outsider at Pop’s, for example—although that was my fault for trying too hard—while I was much more at home at Molotov’s, despite my childhood associations with the clientele’s appearance. It’s the old don’t judge a book by its cover truism. Goodness in a person is not defined by fashion, hairstyle, class, or even questionable life choices. Is someone true to their authentic self? Okay then. We might not agree on even quite a lot in life. But we’ll be able to drink, have conversations, share time together, and look out for one another should anyone come poking about with some ill intent.

Dive bars are often romanticized. It’s an inclination born of that longstanding puritanical American obsession with “authenticity,” whereby the show counts more than the truth. Poverty-porn is big among American fashionistas, or even the average middle class. It’s a very privileged fascination. It manifests in trivial things like jeans designed to look worn out by hard work, or those high-end “pre-loved” furniture stores selling old tables carefully refurbished save their stylish patchy paint job, lacquered with a protective sealant lest its “grunge” get nicked. Poverty-porn also manifests in more destructive ways. Cultural appropriation, misrepresentation, blinding screens systematically constructed between privileged fantasies and social inequities.

A real dive bar isn’t romantic in these ways. A real dive bar offers the comfort of the truth, even if the truth sometimes tastes a bit stale or feels a bit rough.

What I appreciated most about this dive bar hop was the opportunity it gave me to check in with my own authenticity, my own intentions and perceptions.

Why did I walk into one place versus another? Why did I feel more or less comfortable here or there? What assumptions do I make about people, and why, based on what—what that’s to do with them, and what that’s entirely to do with me? Who do I think they and I are? And who are we actually?

A good dive bar is a great equalizer.

Cheers!