Some whiskeys send you off down a long winding road. Others are a single end point unto themselves. What’s the difference?

That old saying—that it’s not the destination but the journey that matters—is a philosophical comment about valuing process over product, that being inside an experience offers more than the completion of it.

There are infinite riffs and variations. The adage about taking time to stop and smell the flowers, for example. Or Oscar Wilde’s observation on his recurring theme of human desires, that sometimes the only tragedy worse than not getting what you want is getting what you want. Maybe because it doesn’t live up to the hype. Maybe because, once you have it, then what?

Though I generally agree that journey and process are ultimately of greater value and importance in life than destination and product, I also agree that one can view a destination as its own process. Last summer my destination was Japan, for example. After journeying there by plane, I spent five days each in Tokyo and Kyoto and every day was a journey. I loved it.

But take any metaphor literally like that and it falls apart. Metaphors do not exist to be taken literally. Precisely the opposite. They are a poetic means of getting at something true about human experiences through a route alternate to the most obvious and direct. Metaphors themselves invite journeys of thought. So for me to use my trip to Japan to poke a hole in the notion that “it’s not the destination but the journey” would be to misunderstand the value of creative perceiving.

So, sticking to the metaphor—what makes a destination whiskey, and what whiskeys are a journey? Here are a few examples of my own takes on that dichotomy. And I’ll say up front, it’s not a divide between “good” and “bad” whiskeys. There’s nuance in these bottles.

Destination Whiskeys

CARSEBRIDGE 52 YEAR

SINGLE GRAIN SCOTCH

I bought this bottle in 2018, two years in anticipation of my partner’s 52nd birthday. She’s not a whiskey geek like me. But she has significant fond memories of Scotland, so I thought this bottle could be enjoyable for us both. And at $381 tax and all, it sure beat the Macallan 52 Year released at the same time—for $60K!

The bottle sat hidden in my bunker until the intended day arrived—the destination of its uncorking. To my delight (and no small amount of relief) it was wonderful. Dark brandied raisins and plums, dried Turkish figs, crystalized honey, spices like cardamom and cumin. In my notes I literally wrote, “What a journey!”

So why not count this bottle among the journey whiskeys then? Each glass was itself a journey across waves of flavor, yes. But two things makes this a destination whiskey for me:

First, the whiskey remained relatively consistent throughout its uncorked life, so I always knew where’d I’d “go” when I drank it.

Second, and more decisively, was its combination of rare age and the opportunity to match that to a gift for the most important person in my life.

So, any time I sipped it, the flavors held true to past sips and my thoughts landed on my dear partner—her long life, her love of travel, our shared appreciation for meaningfully memorable experiences. Sharing this whiskey as a gift was the destination from first pour to last.

🥃

DAKE KANBA

BLENDED MALT WHISKY

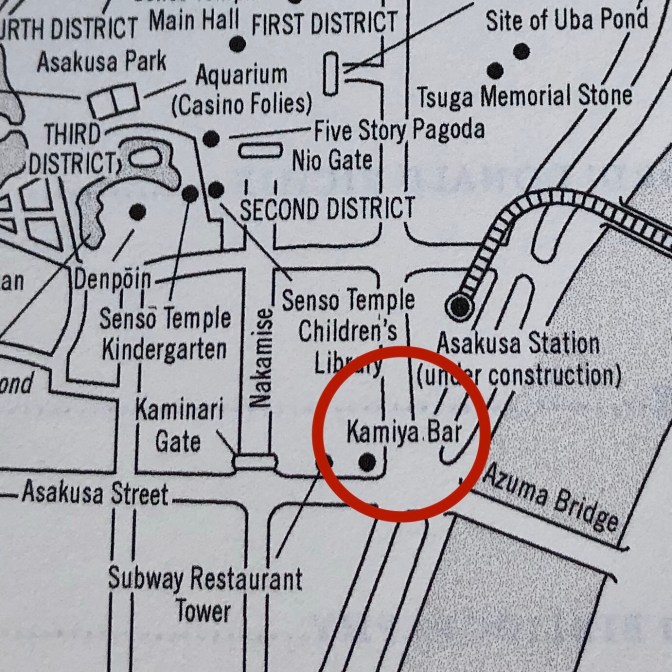

Speaking of that trip to Japan…!

On my last night in Tokyo I went to a tiny bar called Not Suspicious, squeezed into a slim hallway near the Asakusa district’s Hoppy Dori gastro-nightlife area. The owner was tending bar, hosting the handful of us lined up at her single counter like a small gathering of boisterous friends. From the limited selection of whisky bottles on display, I chose Dake Kanba. I loved it!

I was flying back to the US the next morning, so I did not have time to track down a bottle. But I found an online Tokyo retailer that would ship it after me. When I uncorked it a few months later, I quickly realized that a good part of why I loved this whisky was the circumstances in which I first experienced it. In that moment, on that last night of an incredible vacation, pressed up against strangers in a tiny lively bar in Asakusa, that whisky was perfection. But without that timing and setting, it was just okay.

I think of Dake Kanba as a destination whisky due to my own limited thinking. Even on that heady night I first tried it, delightedly delirious from two weeks of travel, I knew in my mind it wasn’t the be all end all. But in my heart in that moment, I believed that having a bottle as a keepsake would mean I could pour a glass full of that moment in the future. But given the experience of the whisky outside of that time and place is so inferior by comparison, now when I pour a glass of Dake Kanba I’m pouring a glass of Ye Olde Lesson Not To Impulse Buy. There’s no journey there. Only destination.

To be clear, Dake Kanba is not a bad whisky. It’s just a boring whisky. As such, it’s nothing like my trip. I’ll likely put most of it toward Highballs, and those will actually be more likely to take me back to better memories of my journey across Japan!

🥃

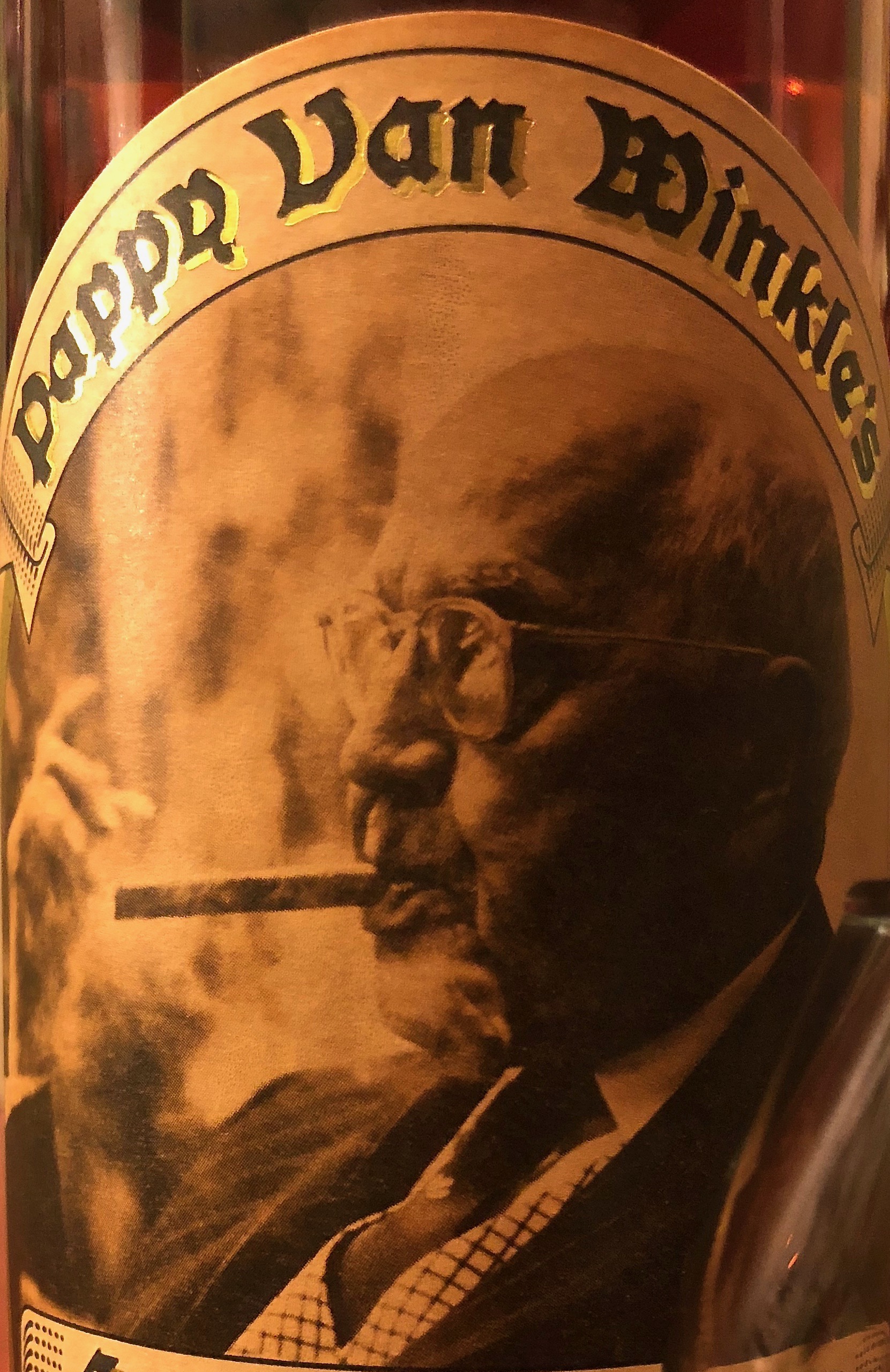

VAN WINKLE

I paused before writing this. At the mere prospect of writing about Van Winkle I could feel boredom creeping around me like the dingy haze of air pollution. I almost deleted this several times. Van Winkle is the cliche unicorn brand. But as a clear example of the old saying that inspired this blog post, few brands are more perfectly suited.

Found at msrp, sure I’d buy a bottle of Van Winkle. That’s how I came into the one bottle of the Pappy 15 I’ve ever had. But that’s a stupid rare occasion. In 2024 even the lowest rung on the Van Winkle ladder, Old Rip 10, which is listed at $70 msrp, regularly goes for $700+ in both the online secondary market and brick-and-mortar retail stores.

One could argue that it certainly constitutes a journey for the average person to find a bottle of Van Winkle. But the admissions on social media from people finding themselves disappointed once they actually arrive at their bottle of it are numerous, to put it mildly. And some people are delighted, of course. There’s no single story here.

With Van Winkle, the easily apparent explanation for its status as a destination whiskey is the hype and cost. The hype is massive and legendary. That ups the price, and the ante. A whiskey better be dang special if one is going to pay ten times the stated msrp. And I’m not personally aware of any commentator who has stated Van Winkle is that good. It’s good, for sure. Just not that good. At all.

Okay enough. Some journeys await…!

🥃

Journey Whiskeys

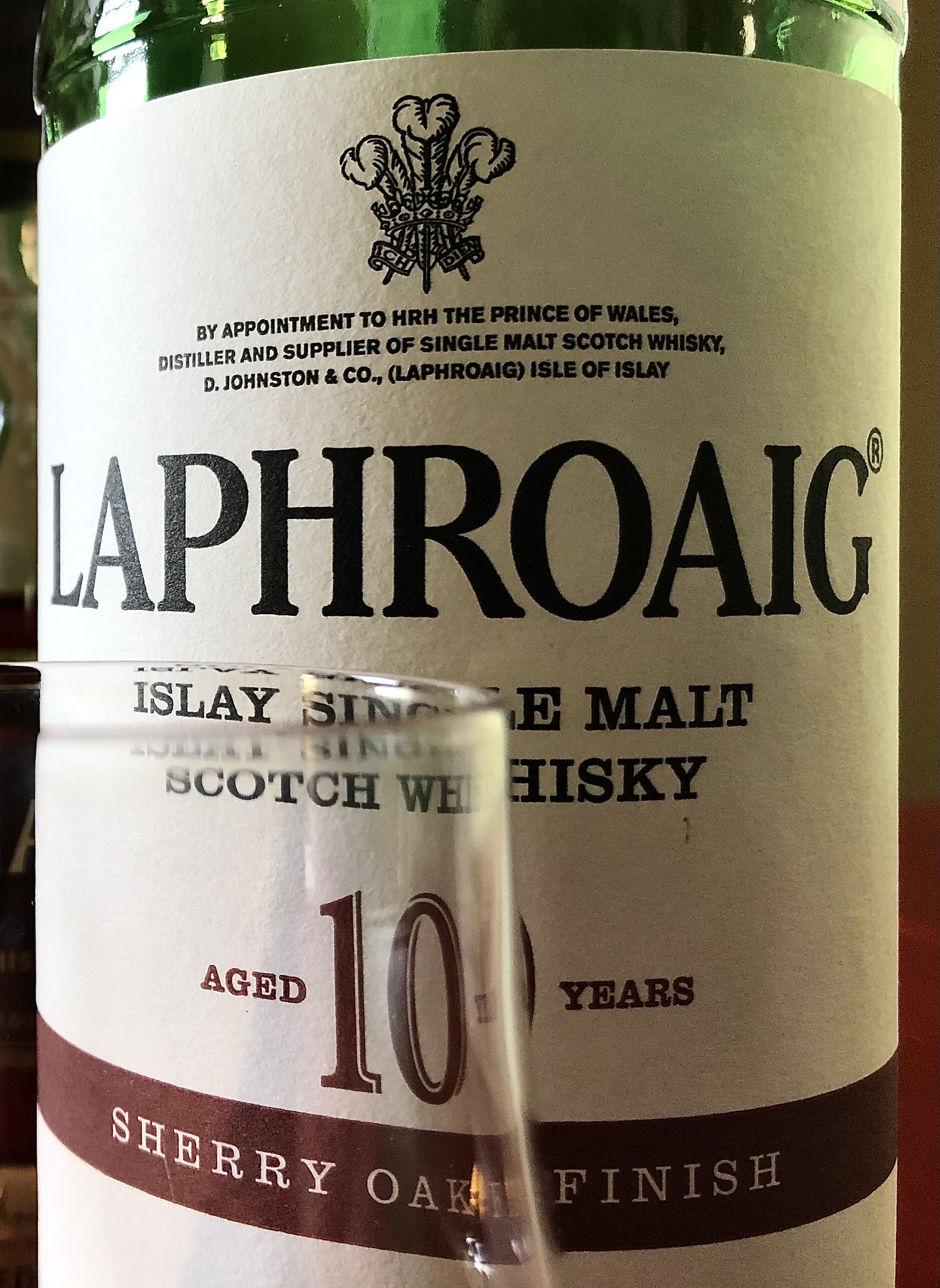

LAPHROAIG

This journey is not about one whiskey but several, all from Laphroaig. It’s a journey about persistence and counter-intuitive curiosity.

My first several Laphroaig experiences were all with various tastings of the ubiquitous 10 Year release—at a pub in Scotland, a bar in New York, when a friend brought a bottle over one night, and a bottle I purchased and suffered through. The medicinal, band-aide aspect of Laphroaig’s ashy peat was simply not something I could abide. Other scotch whiskies with smoke and peat notes—from Highland Park, Croftengea, Kilchoman—I quite enjoyed. But not the Laphroaig 10 Year’s curative vapor.

Yet Laphroaig fans seemed to be in great abundance, singing its praises. I wondered if it was like eating chocolate covered crickets or Anthony Bourdain’s infamous cobra heart appetizer—something so weird and off-putting it attains a theoretical cool from the hipster set. I don’t generally go for that sort of thing. But Laphroaig’s unapologetic intensity wouldn’t shake from my curiosity.

So over a period of years I tried various releases. A 12 Year cask strength bottled by Alexander Murray didn’t sway me. A subsequent Redacted Bros 29 Year single cask release (unconfirmed as Laphroaig but generally understood to be) lacked the band-aides entirely, so much so that I was pretty convinced it might actually be Lagavulin. But overall as a tasting experience it was just okay, and at the asking price “just okay” wasn’t good enough. A fellow whiskey enthusiast graciously gave me a sample from a Laphroaig-direct 30 Year release, which I tried alongside the 29 Year. This helped confirm the 29 Year as Laphroaig in origin, but of course a 30 Year Laphroaig from Laphroaig is even pricier than a sourced bottle, so, still a no go.

Next came an extended experiment with the Laphroaig 16 Year release, sampling it every day for a week to see what making it a regular part of my system for a period of time might reveal. I’d been given a tip by Greg Miller of Capital Liquors that, when sampled each day, Laphroaig 10 eventually settles deep in the apple orchard. This didn’t happen for me. The peat in the 16 Year was heavy on diesel fumes and clay, with a range of fruit notes taking a quiet backseat to the peat. Still not convinced.

And then finally my obsessive pursuit paid off. I rolled the dice on a bottle of Laphroaig 10 Year Sherry Oak Finish. With hopes low, I poured a glass and took a sip. I was shocked. I thoroughly enjoyed it. No diesel. No band aides. And none of the bitter ashiness that often comes with them. The sherry influence was not overwhelming, but very well balanced, with a nice earthy peat smoke paired with chocolate and raspberry compote. Well if Laphroaig could do that…!

So now I knew my route to Laphroaig. Sherry cask finishing! I gambled on another Redacted Bros offering, a 12 Year that didn’t confirm bourbon verses sherry casking either way. But the tasting notes offered a combination of chocolate, red fruits, and cozy woodland peat smoke reminiscent of the Laphroaig-direct Sherry Oak Finish release. I’m still savoring this bottle as I write this, and might eventually break my No Bunkering rule to pick up another.

So this journey doesn’t guarantee that persistence and obsessive compulsive behavior will always end well. But I have indeed found my corner of Laphroaig’s bog, and I genuinely love it. So my journey with the brand will indeed continue, now with a special focus. Another reward is that the heart of my curiosity, suspicious of Laphroaig for so long and resentful of its annoying hold on me, grew at least one size larger.💚😉

🥃

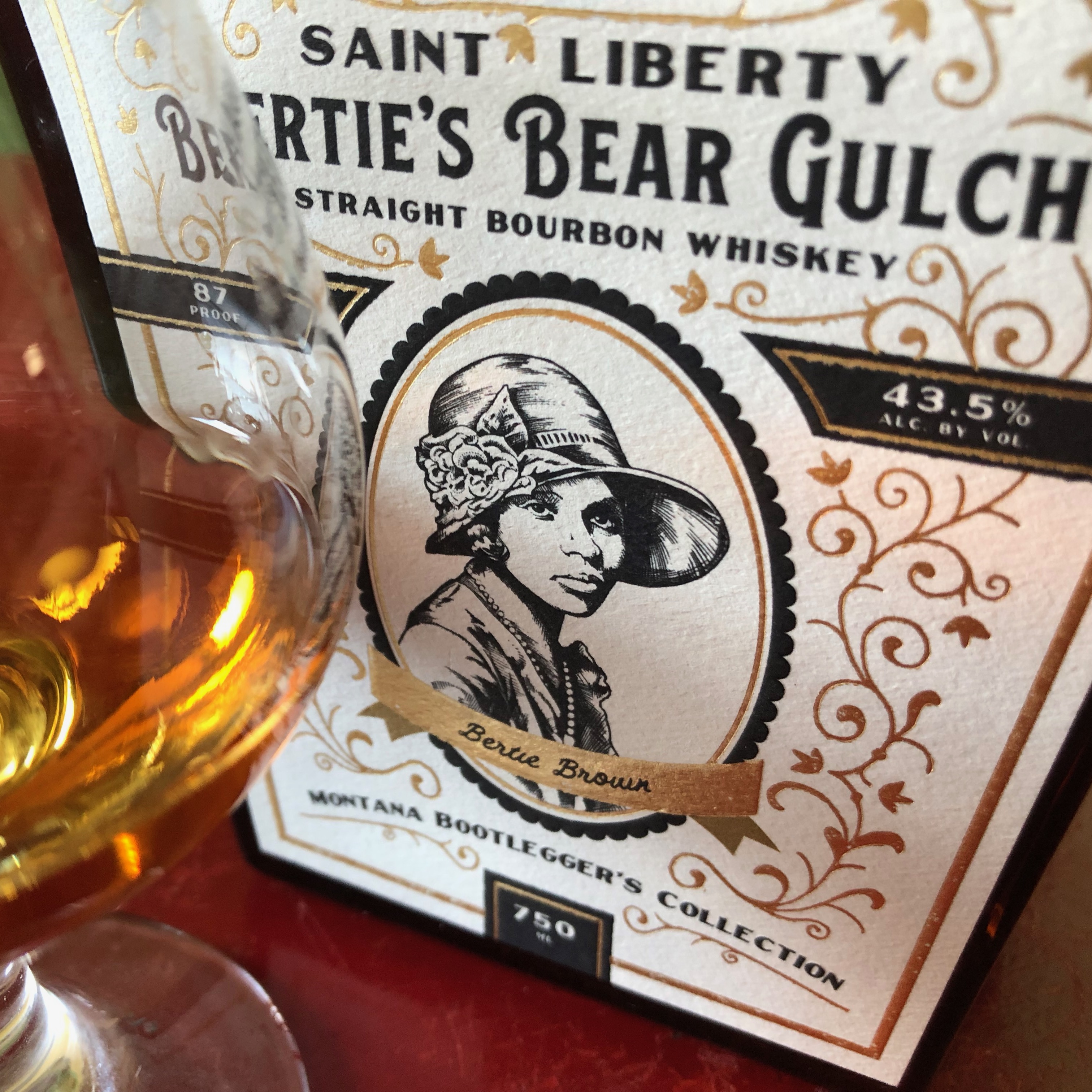

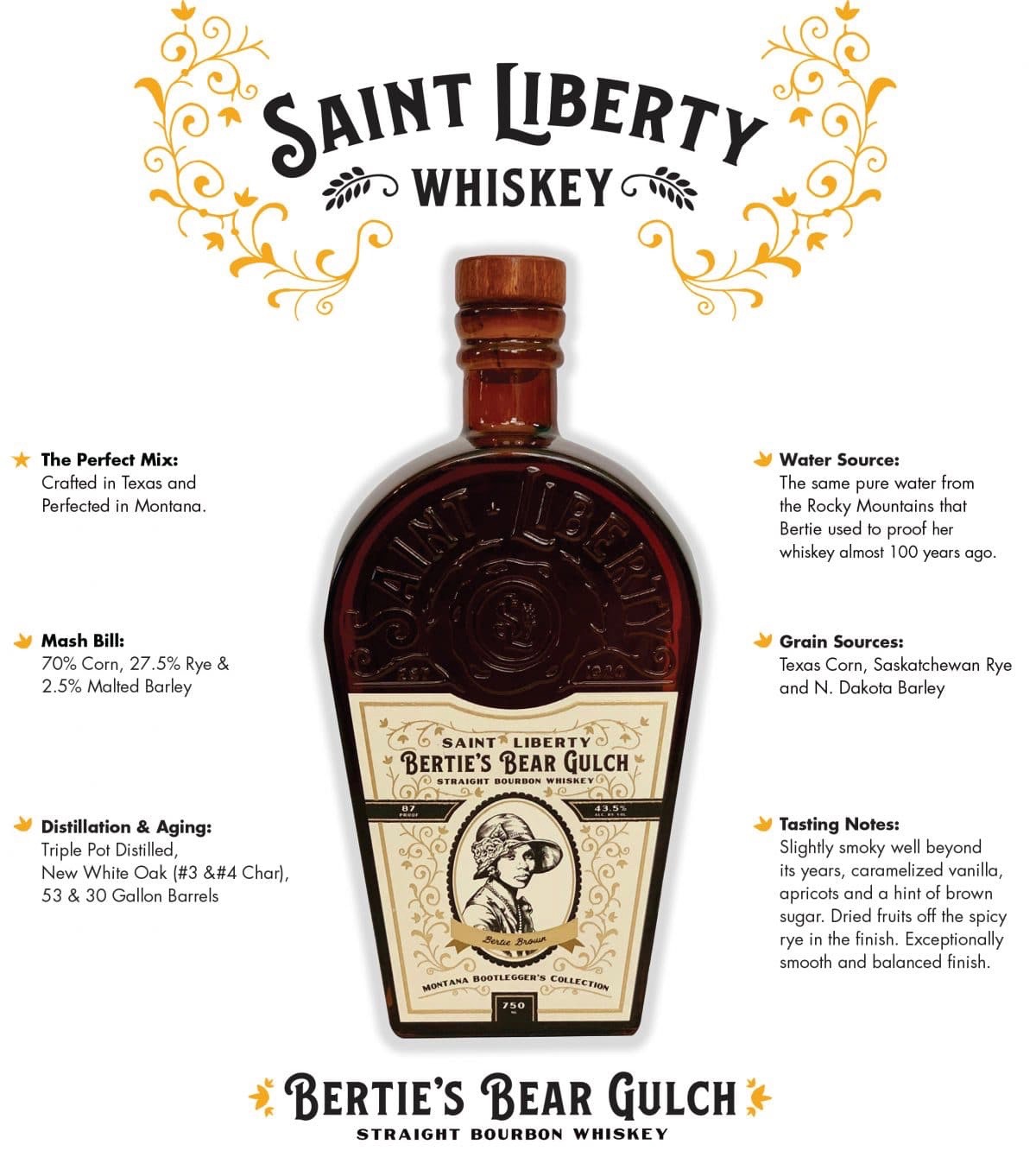

BERTIE’S BEAR GULCH

STRAIGHT BOURBON WHISKEY

Produced by Saint Liberty Whiskey, Bertie’s Bear Gulch is a whiskey I did not like. At all. Now that may seem another counter-intuitive example of a “journey whiskey,” even more so than Laphroaig. But in fact this bottle did take me on a unique journey that has stayed with me, and influenced me, ever since.

I picked up a bottle of Bertie’s in 2019. On sight, Saint Liberty embodied much of what I love about whiskey—namely its ability to evoke stories. Their stated intent is to honor Prohibition-era women whose stories might otherwise go unrecognized. Not celebrities or socialites. Working women. Bertie Brown was among their first, and her story is summarized on her namesake bourbon’s back label as follows:

Bertie Brown – known as “Birdie” to her friends – was a woman of great courage. She was one of very few young African American women who homesteaded alone in Montana in the 1920s. Birdie was famous for her warm hospitality and for brewing what locals called the “best moonshine in the country.” One day in 1933, just before Prohibition ended, a revenue officer came around and warned her to stop her brewing. But as Birdie multitasked, dry cleaning with gasoline and tending to her latest batch of hooch, fumes from the gasoline ignited and her kitchen exploded. Birdie was tragically burned in the fire and died shortly after. Today, her once orderly homestead stands in a state of disrepair in the hills of Montana, a memorial to the immortal spirit and kindness of Birdie Brown.

I loved Saint Liberty’s stated purpose. I loved that five percent of the gross sales revenue of their products go to the PowHERful Foundation, an organization that supports young women from low-income backgrounds getting through college. I loved the transparency about sourcing and other product details on their website. I loved that they commissioned a custom bottle modeled after an authentic 1920s bottle design.

But I didn’t love the bourbon. At all. The flavor notes I picked up were shocking, actually. In writing up my notes for the blog, I included multiple tastings spread out over time, to allow the whiskey to open up, and a variety of tasting glasses to allow for the possibilities of delivery. Maybe it would evolve in such a way that I’d come around…?

It didn’t. The founder of Saint Liberty, Mark SoRelle, read my notes and found them so surprising that he reached out to me and asked if I’d send him a sample from my bottle. Maybe a wayward batch had been sent out? I mailed him a sample, and he reported back that it indeed tasted as intended.

The extent to which I did not like Bertie’s Bear Gulch was such that I even doubted the sincerity of SoRelle’s stated intentions to honor these women. Was it all just an opportunistic #metoo era marketing gimmick? But I found his reaching out to me and how he followed up, in combination with some interviews I read and further developments with the staffing of Saint Liberty, to all be signs of integrity. Later I tried another Saint Liberty offering, Josephine’s Flathead River Rye, and it was exceptionally enjoyable.

So the journey for me here was between two destinations: the whiskey itself and its story. For me, they were in complete clash. I shared every value the producer espoused, the intention, the attention to detail. Yet the whiskey itself was so off-putting I could barely drink it. Theory and practice in utter conflict!

Yet SoRelle’s attentive response; and that another offering from the company, the Flathead Rye, was excellent; plus the opportunity Bertie’s Bear Gulch gave me to slow down and test my tasting experience with repeated and varied trials—all of this was a journey around the connection between my mind and body, my conscious values versus my in-the-moment visceral experience. More than any whiskey prior, Bertie’s Bear Gulch helped me learn to do my research as a whiskey taster. To take my time. That tasting is not a one-and-done process. Talk to the whiskey’s maker if I can. Ask questions. Explore. Stay on the journey’s winding paths.

And all of that earns Bertie’s Bear Gulch Straight Bourbon Whiskey a special place on my whiskey journey’s proverbial shelf. I don’t need to buy another bottle. But I appreciate the one I had. Bertie’s contributed significantly to my learning how to taste.

🥃

WESTWARD WHISKEY

It is Westward Whiskey that led me on my most significant journey with barley. Through Westward’s single malt whiskeys, I’ve learned to discern how the barley grain itself variously supports, bursts through, or melds with the other flavors coming from the yeast, water, oak, time, etcetera.

In 2021 I interviewed Westward’s founder, Christian Krogstad, and he took me on a tour of the distillery. We began at a glass jar of raw barley grains, a small handful of which he poured into the palm of my hand with a small scooper and instructed me to toss it back. It tasted a bit like Grape-Nuts cereal, a dry nutty-fruity combo.

This was a key moment. Now with the pure taste of raw barley infused into my senses, we made stops to sip at every stage of the process—the fermenting vat, the first distillation, second distillation, and finally a flight of eight different Westward Whiskey variations. Throughout, I could track the evolution of the barley flavors as they made their way through the process from grain to glass.

Now whenever I drink a Westward Whiskey, I clock that particular barley note right away. Other notes then gather around it, like they’re cozying up to a bright warm fire. These can range widely—rooibus tea, chocolate fudge, salted caramel, prune, plum, meaty orange peel, fresh peach, stewed apricot, toffee, coffee, malt… The barley notes anchor any Westward Whiskey. The variances gathered around it provide the nuance.

As I type this up, I’ve just uncorked Westward’s summer 2023 whiskey club release, dubbed Westward x Ken’s Artisan Sourdough Whiskey Second Edition. (The first was in 2020.) For this release, rather than using Westward’s standard pale ale yeast, they used that of a French sourdough levain from award-winning baker Ken Forkish, of Ken’s Artisan Bakery in Portland, OR, where Westward is also based. The result?

From the nose I got sourdough, for sure—a very creamy, doughy sourdough. From that the Westward barley soon emerged, leaning a bit toward apricot. On the taste, the first word out of my mouth was Seriously? It was so good right out of the gate. Tasted blind I’d have guessed it was a scotch. Smooth, creamy, with bright orchard fruits from the barley, then mocha, coffee, toffee, a nice bitterness from the sourdough yeast and oak. On the finish, the bitter notes then heightened nicely around the core barley fruit notes.

Overall, the sourdough notes are the obvious attraction here. But the way the bitter aspects play a role is unusual, giving way to a mélange of classic bitter qualities like grapefruit peel, oak tannin, malt. Rather than overpower, they support the sweeter barley, fruit, cream and candy notes.

Westward does it again. The journey continues. And because of my detailed journey with Westward, now when I taste single malts from other distilleries I’m better able to unpack what I’m experiencing.

🥃

Last Call

So I suppose the broad distinction between Destination and Journey Whiskeys could be this:

Destination Whiskeys tend to arrive and stay there. They don’t compel my curiosity further down the road, its side paths, or any nearby rabbit holes. Maybe it’s that the whiskey itself is so consistent as to be predictable—which might be a great thing, as with the Carsebridge 52 Year, or a poor thing, as with the Dake Kanba. Maybe, as with the Van Winkle, it’s been hyped and/or priced beyond any experiential rewards one might hope for when sipping it. Or maybe it was first experienced on some special occasion or in celebration of some very particular moment or person, and so forevermore that whiskey is only and all about that time, place, or person. In any example, a Destination Whiskey has a singularity to its impact.

Journey Whiskeys, on the other hand, whether pleasing or not, tend to send me across the map in different directions. My curiosity jumps on board for the ride and stays there, either for some significant time or in perpetuity. Maybe I’m trying to unpack the precise appeal of something, as with Laphroaig. Maybe it’s a learning curve I’m navigating, as with both Bertie’s Bear Gulch and Westward Whiskey—two very different journeys for me, but both worthwhile for their respective reasons. Journey Whiskeys take me places, plural, not to any single place.

And of course all of this is quite subjective. What might be a Journey Whiskey to one person is a Destination Whiskey to another. One whiskey fan’s heavenly destination might be another’s hell in a glass. One person might feel frustratingly lost on a journey, while another is perfectly content to wander and see what comes.

All reasons to pour another glass and share stories from the journey.

Cheers!