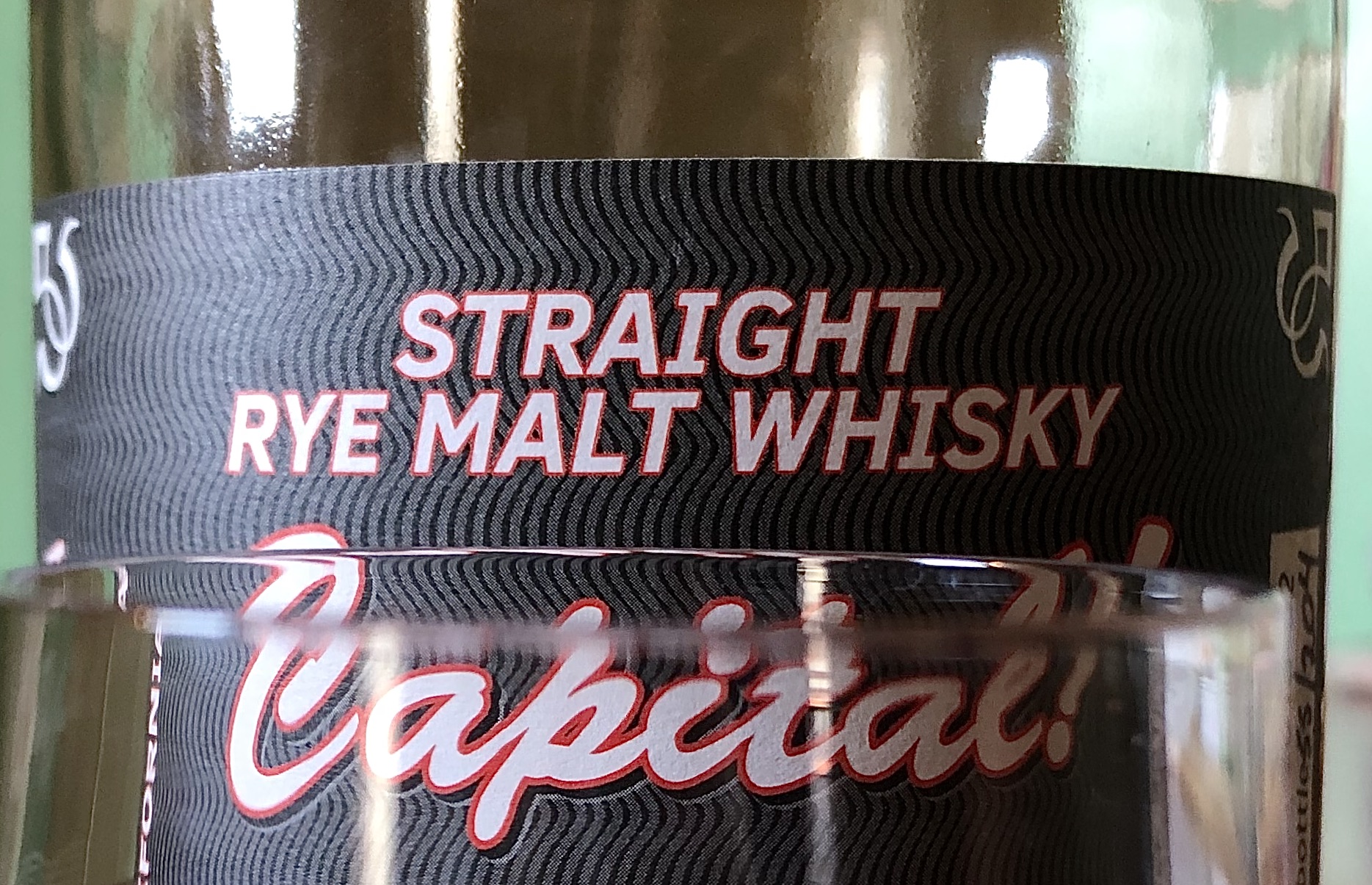

CAPITAL!

Cask #2015-02 (bottled late 2021)MASH BILL – 100% malted rye

PROOF – 106.8

AGE – 5 years

DISTILLERY – Capital Liquors Project

PRICE – $55

WORTH BUYING? – Yes

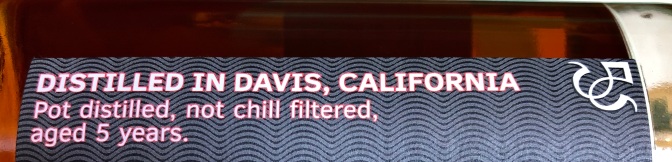

Greg Miller is a professor of chemical engineering at University of California Davis, just a short drive north of San Francisco near the state capital of Sacramento. Other than that, very little publicity info exists about Miller, the distiller behind this whisky, nor about the “Capital Liquors Project” that produced it. The label looks much more like a private barrel pick sticker than an official brand label. Is this bottling a one-time project? The thesis of a UC Davis classroom experiment? Or the start of something very interesting?

There is a 2019 in-house article posted on the UC Davis website about Miller, featuring the publication of his book, Whisky Science: A Condensed Distillation. But nothing there sheds light on this particular rye whisky. K&L, where I bought the bottle, provides the most detailed information on their own website. In short:

Fermented “on the grains” from 100% malted rye, the distillate is double pot distilled under direct propane fire. It is aged in Missouri oak casks, coopered in Napa, which were air-dried for two years and then given a #2-level char. The spirit went into the barrel at 102 proof and aged in a warehouse with a notably wide seasonal temperature fluctuation. After 5 years, the whisky was only minimally filtered to remove residual cask fragments, and bottled at cask strength.

From K&L we also learn that Capital Liquors Project is “likely the nation’s smallest licensed distiller situated on the outskirts of Davis.” Via the TTB website, I managed to track down the location, a remote strip of road adjacent to the Yolo County Airport, seen here courtesy of Google maps:

Of course, I could reach out to Miller via UC Davis for more details. And I will. (See below!) But I thought it more interesting to taste the whisky first, knowing only what I do as I write this now. This might keep things closer to most whisky tastings, where some modicum of basic information is known and the experience cannot yet be influenced by any inside scoop.

Like other whiskies new to me, I might also relate the specs to whiskies I’ve already had in anticipation of what this Capital bottle might offer. Old Potrero is a 100% malted rye whiskey, aged a similar number of years though in a very different climate—San Francisco does not have the wide temperature swings typical of the flat central California valley where Davis sits. Old Maysville Club is another 100% malted rye, aged a similar 4 years, but from an even different terroir than anywhere in California—Kentucky. Both these examples offer strong malt flavors, with very different impacts: Old Potrero is consistently among my favorite ryes, whereas I gave away my last bottle of Maysville Club halfway through it. Which way will Capital go?

Let’s find out! Here we are, six weeks after uncorking and four pours into the bottle. Tasted in both a traditional and Canadian Glencairn, here are some notes in brief:

COLOR – yellow and orange ambers that glow in the light

NOSE – malt malt malt, freshly baked and cracked-open loaves of rye bread, a subtle nutty-fruitiness I associate with malted barley, faint crystalizing wildflower honey, faint drippy caramel, all very pleasantly dry like early autumn before the rains come

TASTE – malt malt malt, dry but soft and supple, with milk chocolate, a bit of graham cracker, a splash of fresh cream, sun-dried rye grasses, a lovely creamy texture, and a nice soft prickly pepperiness from the surprisingly gentle 106.8 proof

FINISH – malt, graham cracker, chocolate, the prickly heat gradually fading and leaving a nice blanket of warmth in its wake, the cream note now more like whipped cream in a hot chocolate

OVERALL – If you like malted rye and don’t mind a dry whiskey, this one’s for you.

Obviously, malt is the big theme here. It’s a much softer, for me far more enjoyable maltiness than Old Maysville Club, which had a harshness and hardness to it. This Capital rye is much more easygoing. It’s dry, for sure, but without any unpleasant edginess grating at the palate. The subtle cream and chocolate notes, combined with the velvety texture, keep things smooth and mellow.

Compared to my sense memories of the various Old Potrero’s I’ve had, the Capital lacks that brand’s richer complexity, darker more decadent chocolates, and dependable bursts of dark fruit notes. Capital is dry like the flat central Northern California region where it’s made, with a brightness and clarity like the steady sunshine there.

Despite the Capital’s cheaper price and interesting origins, when I’m craving a single malt rye I’ll more likely reach for Old Potrero. Capital is quite pleasant. But I do prefer a bit more sweetness to balance this kind of malty dryness. And the chocolate and cream notes don’t quite figure in prominently enough to complicate things significantly. As a longtime resident of the arid Northern California climate, I fully appreciate Capital’s particular effect. Though that’s not enough for me to buy a second bottle, I will certainly enjoy this one and recommend it to anyone who likes the flavors noted up above. It’s quite an impressive accomplishment for such a tiny operation.

Cheers!

Interview with Greg Miller

With my curiosity thoroughly piqued by this whisky, I reached out to Greg Miller via his UC Davis email address and asked if he’d be open to chatting about his rye. Delightfully, he was.

Immediately in our conversation, Miller impressed me with his lack of talking points. He was not a practiced brand rep, schooled in how to deliver a sales pitch in the guise of casual conversation. He had the genuine passion I associate with distillers like Todd Leopold of Leopold Bros or Jimmy Russell of Wild Turkey. But he wasn’t selling a thing. His responses to my questions were driven by pure, undiluted curiosity.

Here’s our conversation…

MARK – What is the Capital Liquors Project?

GREG – I got interested in trying to understand whiskey, the chemical basis of it, what makes one thing taste different than another. The only way to experiment with that is to be a licensed distiller, because there’s no such thing as a hobby distiller who’s on the correct side of the law. And my wife’s a lawyer, so, I had no choice but to become a licensed distiller if I wanted to pursue that hobby.

So that’s what it is. I make a couple barrels a year. I try to use it as an opportunity to test my understanding of what’s happening. But I have to sell it in the end because that’s how the law works.

So this is a private business of yours, and not something affiliated with UC Davis?

That’s correct. I would do it at UC Davis if I could. But the way California law is written that would be illegal. I’m allowed to teach it there, but not to make it.

In describing the whiskey, K&L mentions it is “fermented on the grain.” What does that mean exactly?

By contrast, if you’re making beer you would try to draw off a clear wort that doesn’t have any grain in it before you do the fermentation. But when you’re making rye whiskey, rye doesn’t have any husks so you can’t do that separation. The whole thing is like oatmeal, and you have to ferment the oatmeal. Then you have to distill the oatmeal, which is a big old mess.

Can you talk about the choices you made—mash bill, entry proof, the particular still you use, aging it 5 years? What were the questions and interests that drove your decision making for this batch?

The easy one there is the 5 years. I just tried it every once in a while, got to 5 years and said, Okay, this is ready to go, time for me to figure out how to sell it.

Regarding the still, I built it—and it was, let’s say, budget limited. Because I’m not doing this at a commercial scale, more of a hobby scale, I didn’t want to have to take out a loan or get business partners. Rather than investing two million dollars I invested about two thousand dollars. I just built something.

You built the still?

Yes, but let’s not give me too much credit. I barely know how to weld. I can solder. But metal work is not my forte. You would recognize it as a still. But if somebody was putting this still on eBay, you wouldn’t touch it. It’s not a thing of beauty.

What led you to choose the 100% malted rye mash bill? It’s less common for people to do.

When I began this journey there weren’t a lot of malted rye whiskeys on the market. That’s changed a lot in the last ten years. But I was strongly influenced by Fritz Maytag’s project with Anchor Distilling, where he was trying to create heritage rye recipes. So I wanted to explore that. If you use regular, un-malted rye, then you have to provide enzymes, either by using a little malt or exogenous enzymes—something you would buy from a pharmaceutical company. There are certain styles of beer that use rye, and a couple malting houses in America that malt rye for that beer market. So I thought I’d start there, and then I could try to understand the essence of rye and keep it natural. That was my thinking. The flaw with my thinking is: if you think about a Lowland scotch versus an Irish whiskey, there’s a big difference there, right? And I think that’s due to the use of un-malted grains in Irish whiskey, which is a signature Irish thing. So, I went to malted rye, and now, in my quest to understand rye, I need to go back and account for the effect of malting.

And what does that accounting look like, what will you do?

Well at some point—and I haven’t done it yet—I will have to buy some rye that’s not malted, treat it with exogenous enzymes and make some whiskey from it, let it sit for 5 years, and see how it differs.

Is the bottle I have the first batch you’ve sold, or have there been previous bottlings?

When I first began the project, it was at a much smaller scale and I didn’t have a proper license. I had a license to make fuel. That involves a lot less paperwork, but in the end you have to burn it. So I was basically making whiskey in jars, aging it in jars with little chunks of wood. But then it would get redistilled and used to power a lawnmower. And I did that because I knew from the beginning that I could make alcohol. But I had no idea if I could make alcohol that would taste any good.

Remember, this is a hobby scale effort. I was paying for this out of my pocket, so, I didn’t want to spend a lot of money until I knew it had the potential to be worth the effort.

So, I did that for—I don’t know, three or four years—until I thought it had potential to be good. And then I got the proper licensing to make whiskey and I stopped making lawnmower fuel. So what’s on sale at K&L is the first bottle. It wasn’t from the first barrel. The first barrel is going to be a year older when I get around to bottling it. The one I chose to bottle was more accessible, in that it was at the front of my storage area. So it wasn’t a scientific choice, just that I could physically get to it more easily.

They all taste similar. There are variables, I change things from one to another. But there is definitely a house character. So if you like this one, you’ll like the others. The one at K&L now, I barreled around 100 proof, which used to be the American standard before Prohibition. Now you’re allowed an entry proof up to 125, so, I also made a barrel at 125 to understand firsthand what that does.

And is that choice between a lower versus higher entry proof one made with regard to flavor, expense, or both?

In the real world?

Well, arguably, your whiskey is now in the real world.

I did it to explore that variable. In the real world, most everybody goes in at 125 proof, except for some craft people, because it cuts down on barrel expenses. Barrels are very expensive.

I have difficulty wrapping my mind around why a higher entry proof is cheaper than a lower entry proof. Why is that?

At a higher entry proof, you’re putting more alcohol into a given barrel, which you can then stretch out into more bottles by adding water after it’s been aged. But lower entry proof, we think, leads to more extraction of flavor components from the wood. So, probably, you’re giving up a little flavor when you’re trying to be economical by using a higher entry proof.

And is that because at a lower entry proof there is less competition between the flavor impact of the alcohol and that of the wood?

No, it has to do with the chemistry of extraction. It’s the chemical interaction between the whiskey and wood in the barrel that’s effected. It just turns out that a lot of the flavors you care about are more extractible into water than into alcohol.

This bottle I’m holding is listed as cask 2015-02.

The year 2015 is when it went into the barrel, and that was barrel number two from that year.

And how many barrels did you do that year?

Two. Barrel 2015-01 will emerge at some point.

Is that the one that went in at 125 proof?

No, that was the third barrel, which I think was 2016. But that’s off the top of head, so, I’d have to refer to my log books to be sure.

So, you’re really going barrel by barrel to try out different combinations of making-factors and how those impact flavor.

Well, there are some experiments you can do on a quicker scale. My still is small compared to the size of a barrel, so, I’ll distill maybe thirty mashes to fill one barrel. That means I’m doing potentially thirty different experiments on fermentation and distillation that get averaged when I load up the barrel. So, while I’ve only done, so far, six barrel experiments—that’s how many barrels I have right now—I’m doing hundreds of distillation and fermentation experiments. I’ve only once had a fermentation become so sour that I didn’t risk using it. It had gotten contaminated. I’ve used all the others. Now, I do have two barrels of whiskey that I may turn into lawnmower fuel because I don’t like them. I’m not going to sell anything if I don’t like it.

Are all six barrels rye?

The two I don’t like were bourbon experiments, and I’m not sure what I did wrong. I have a theory. There’s a popcorn aroma that comes off near the tails of a bourbon distillate that’s really cool. And I wanted to grab that. And that made my distillates a little more tailsy than they probably should have been, because there are other flavors that come out with the tails, like sulfur compounds that don’t play nice over time, and they’ve left their fingerprint on this whiskey. I’ve tried to do things to reduce that, like running it through charcoal. The jury is out whether this is working and whether it’s going to be any good.

So you have six barrels total—two rye, two bourbon, and what are the other two?

A grand total of three are rye. Two are bourbon, and you may never taste them. And the sixth barrel is a peated malt. My personal passion, flavor-wise, is peated scotch whisky. They’re really hard to make because the key ingredient doesn’t come from around here. There are some suppliers of malt that’s prepared in Scotland with peat, and you can buy that. It’s a little bit spendy. But I wanted to do it because it’s what I love. It’s not really an experiment in the sense that I probably won’t repeat it, and doing it only once you don’t learn that much. But I did learn one thing!

What’s that?

So, you very rarely see a good scotch that’s three years old or so. Mine tastes really good. I don’t know how it happened. It might be luck. It might be that the barrel I used had a little more life in it than the average scotch barrel. They tend to use relatively depleted bourbon barrels. I used one of my rye barrels that had held rye for only a year, so, it was a young barrel that imparted a lot of flavor. Another reason may be that Davis is a lot hotter than anywhere in Scotland, and chemistry happens faster at high temperatures. It’s my proudest accomplishment, but I may never repeat it.

Do you have plans yet for when to bottle that one?

Well, you know, there’s the three-tier system of distribution: I’m only allowed to sell through a distributer, and a retailer like K&L is only allowed to buy from a distributer. I’m using LibDib, based in San Jose. They only exist on the computer. So K&L issues an order, I put stuff through FedX and it goes to them. LibDib has nothing to do with shipping, just facilitating.

The reason I mention all this in answer to your question is that, when I went to K&L and said I’d love for them to carry my stuff, they said, okay, here are four or five distributers to go through. And LibDib was the only one that would handle me, because they don’t care how big I am. Any more traditional, hands-on distributer won’t handle me because I’m more paperwork than I’m worth. But what LibDib did is open this direct channel between me and K&L. Right now, K&L is the only store in the world carrying my whiskey.

So there’s hope I might be able to get your single malt from K&L one day.

I hope very much that it shows up at K&L soon, like next year. And the reason I’m pushing soon is because I think it tastes really good at this young age, and I don’t know if it will continue to improve or become mediocre as time progresses. To hedge my bet I want to get it out while it’s good.

Why whiskey and not wine or beer?

Because I drink a lot of whiskey. That’s the true answer. There used to be a group of faculty in the College of Engineering at UC Davis who would get together every couple of weeks and drink too much. And I started bringing research papers to those meetings. I wanted to slow down the drinking and do more contemplation, and my colleagues didn’t want to go there. I enjoy a glass of wine or a beer. But I really enjoy whiskey, and I want to be a better whiskey drinker. I want to do more thinking and less drinking. You must have gone on a broadly similar journey in becoming a bourbon steward.

Yes, and I never would have guessed it beforehand. It’s to my own surprise that I became a whiskey aficionado. When I first started, I could still count on one hand how many cocktails I’d had in my lifetime. I grew up in Placerville, a minor wine country, and we always had wine around the house. Then my partner and I lived in Germany for a while, where it’s all about the beer, so, I got to know beer. Then one Summer my Dad put some bottles of whiskey in front of me, I liked them, and a month later a trip to Scotland cinched the deal. And the more I got into it the more I became interested in the history of it, and it’s connection with political and social history.

Fantastic. Are you familiar with the text book I’ve written?

I know of it from researching a bit about you, but I haven’t had a chance to read it yet, no.

The first chapter is about the history of the product and how it’s methods of production have changed over time. But along the way I learned the history of other things, like the history of how we measure the density of liquids. I think a normal modern scientist would read my book and say that 20% of it is of no current value. And that would be a fair criticism. But that’s all to say I agree about the allure of the history of the whole thing.

Is there anything else I should ask you about that I haven’t already?

I’d just say, I’m really a hobbyist. I’m not doing this to make a buck. In fact, I probably lose a buck or two on every bottle sold. But if I joined a country club and played golf instead, I’d probably be spending even more on that hobby. So, we make sacrifices for our hobbies. I’m trying to sell only really good stuff. If it’s not good I won’t sell it. Fifty bucks a bottle sounds like a lot, right? But not when you’re operating at my scale. It’s a different thing when you buy a bag of malt, as opposed to when you buy a train car of malt.

The other thing I’d like to say is, since whiskey is so subjective, everybody has a different experience. And you know from your steward studies that everyone has a different flavor sensitivity.

Yes.

I just found out last week that I’m completely blind to the bitterness of caffeine. Sixty years old and I had no idea!

How did you find that out?

I have a colleague who teaches about coffee. He has standards of sour and bitter in order to teach his students the difference. So, I tasted the sour—it was unsweetened lemon juice. And I tasted the bitter, and I could tell there was something there, that it wasn’t just water. But it wasn’t bitter. And he said, “Well, if that didn’t taste bitter, try this,” and gave me something ten times more bitter. And again I could tell it wasn’t water. But it still wasn’t bitter. It turns out these were caffeine, commonly used as a standard for bitterness. This was the first time I’d had unadulterated caffeine, and it had no flavor impact on me at all!

The reason I bring that up is because, first of all, I’m flavor deficient in the bitter department. And that connects to your tasting notes in your Instagram post. You mentioned walnuts.

Yes, I did.

So I went back and cracked a bottle of my stuff, and I was determined to find the walnut. I can’t find the walnut. I’m not disagreeing with you. I’m thinking that maybe I have other defective tastebuds, who knows?

Or maybe what I’m describing as walnut, you might be tasting the same thing but describe it as something else.

Maybe.

If someone has never consciously had nutmeg in their life, they can’t identify it. They might taste nutmeg, but not know what to call it because they don’t have a conscious sense memory of it. I notice for myself that I pick up on layers and layers and variations and variations of oak, and I believe that’s because I grew up around a lot of oak, all year round. So I’m particularly sensitive to it. I’m fascinated by how where we were raised, combined with our physiology, impacts how we taste things.

It’s a real puzzle. I didn’t grow up around walnuts. But I’m certainly surrounded by them now. I have a five-pound bag of them in the pantry that I snack on, so, I think I’d recognize the flavor. But in combination with whatever else is going on in the rye, I cannot find it. I feel like I’m missing something, that you’re getting a more enriched experience than I am, and I feel cheated. [laughs]

So that Instagram post had some very brief notes from when I first uncorked the bottle. But I did a more formal tasting for the blog a few days ago, and—I’d have to go back and look, but—I don’t think I was picking up on the walnuts anymore. Some people debate whether or not a whiskey’s flavor changes after it’s been uncorked. In my own experience it does, some more and some less. But it’s often been the case that at uncorking I taste things that I either never taste again, or they go away and come back at some later time.

This is making me think I might just do another round of formal notes on your rye after this conversation, to see what the combination of more time plus more inside information from you does to my experience of it.

That’s interesting.

This is a parallel for me between whiskey and my other work, theater—how we perceive things over time. How I perceive a bottle of whiskey from uncorking through to the final pour changes, it evolves, in the same way that a theater production on opening night has changed and evolved by closing night. They aren’t movies that are frozen forever. They’re live, whiskey and theater, and they’re changing as they “air out.”

Let me tell you about another experiment I did. A year or so ago, when we had the tariffs on whiskey, I ran over to Costco and bought a case of Laphroaig, because I love it and didn’t want to find myself shorted. And so I had an opportunity to discover what happens when you drink a lot of Laphroaig. If you drink it just once, out of the blue, having been drinking other things, it’s a pretty peaty, medicinal spirit. But if you drink it every day—in moderation—it tastes unbelievably sweet, like apples. And drinking it every day, I don’t get any medicine or brine. All I get is apples, so much so that I don’t like it. I have to stop for the peat to then come back. And I don’t know if it’s in the head or in the tongue, if maybe you numb your tastebuds with repetition. And again, I’m not talking about alcoholic amounts. Just a normal pour. But you drink it every day and it becomes sweet.

Is it chemical, perhaps? Because if you have it every day, and given it takes a couple days for alcohol to fully leave your system, then as the days accumulate with a steady intake of Laphroaig, maybe, chemically, your tastebuds respond differently as your body develops some base-level of Laphroaig.

I agree that makes sense. I can also convince myself that it’s more in the mind.

That just knowing you’ve been drinking a lot of Laphroaig, it’s less of a shock the second and third time around and familiarity sets in?

Exactly. And you become more attuned to flavors that are more in the background.

Right.

Anyway, it’s an experiment you can do on your own. But it may upset your tastebuds a little bit.

I might try it. I am a big fan of peat. And Laphroaig has been a kind of gargoyle staring me down, because, of the peated whiskies, it has a particular medicinal quality I struggle with. So I would be curious to try your experiment and see what it does for me. I’ve also had friends who do like Laphroaig tell me I should try the older releases, that something happens to the peat when a barrel has a lot of years behind it.

K&L has had a few 20-plus-year offerings, and those are the most I’ve ever spent on a whisky. I’ve always felt it was money well spent. Although they’re not all equally good. Age does not create perfection. It changes things.

Sometimes for the better, sometimes for the worse.

I wouldn’t say it’s ever for the worse. All the 20-year Laphroaigs I’ve bought were better than the 10-year. But some were spectacular while others were merely good. So yes, put that on your list.

I will. Well, thank you so much. This has been great.

Absolutely. I look forward to reading your work.

Post-Convo Tasting

Inspired by our exchange around tasting notes, I indeed went back to give the whisky a second formal tasting. This round of notes was taken later that same afternoon that Miller and I spoke, which was itself four days after the formal tasting noted up above. Here’s what I picked up this time around, now with more backstory in my system:

COLOR – a lovely soft orange-amber with glints of polished brass

NOSE – malt, straw and hay, cinnamon

TASTE – rich and chewy malt flavors (if malt were a syrupy dessert sauce made to top ice cream or chocolate cakes this might be it), cedar hewn into lumber, thick oak planks, eventually on further sipping the chocolate and coffee begin to emerge

FINISH – malt, rye and wood spices, dried caramelized sugars, a nice lightly biting prickle on the sides of the tongue

OVERALL – a celebration of what malting rye can do, emphasizing the drier possibilities of grain and wood

So my conversation with Miller did not pull forth any significantly new or different flavor notes. Nor did that walnut note I got at uncorking make a return. But certainly my appreciation for what is here is heightened. As an exploration of malt, rye, and wood, served up with an inviting, syrupy texture that helps the dryness go down with greater ease, Capital Rye is a welcome bottle on my shelf and in my ongoing exploration of rye whisk(e)y. Rye is a rambunctious grain, with a kind of mischievous penchant for surprise that continues to fascinate me.

Can’t wait to try that peated single malt Miller mentioned!

Cheers!

UC Davis is my alma mater, so my interest was already piqued at the intro paragraph. But it’s that conversation with Dr. Miller that was an absolute delight.

Clearly, he approaches his whisky-making with his scientific, logical mindset. But his genuine interest and passion shines through his dialog. Knowing that he won’t push bad experiments out to the public, and that K&L will carry those batches he himself enjoys – I’m going to have to keep my eyes out for Capital Liquors Project – and pick up one of the remaining 18 bottles of this 2015-02

Thanks for being curious enough to contact the distiller, and bringing out a fuller story to this whisky!

LikeLike

Thanks! I thoroughly enjoyed getting to know Greg. Can’t wait to try that Single Malt he mentioned! Cheers!

LikeLike

K&L has the peated single malt in stock now!

LikeLike

Yes! Very excited to try it! 🥃

LikeLike